I

My father was a man of excellent judgment. In my early youth he decided that my brother should have a college training, and that I should remain on the farm and follow the calling of my seven generations of New England ancestry. This early decision would have been effective had I not attended the Dartmouth Commencement in the summer of 1865. I was present on that occasion upon the invitation of my father, to witness the graduation of my brother. When I gazed upon that senior class, clothed in long black coats, light gray trousers, and tall silk hats, marching from Dartmouth Hall to the old College Church to the strains of martial music by a New York City band, my faith in the wisdom of my father's decision wavered, and later in the day, as I sat in the church and listened to a salutatory in Latin delivered by Mr. Edwin Blaisclell Hale of Orford, and observed the ease and delight with which the College Trustees and the members of the graduating class grasped that ancient Roman language, and applauded the sentiments of the orator, I was strongly impressed that college life was far better than life on a farm. After listening to twenty-four orations and disputations, we returned to the Cornish farm, the quiet life of which was not disturbed by the music of a New York band, and the language of the ancient Roman was never spoken.

For more than a year I concealed and suppressed my ambition to go to college, but like Banquo's ghost, it would not down, and finally I appealed to my parents, who readily agreed to allow me to leave the farm and prepare for college. My preparation was constantly interrupted while at Meriden, and I found myself in the summer of 1870 unprepared to enter college. I then decided to go down to Exeter for one or two years. During the first month I met with an accident, and was granted leave of absence for a week, and returned to my home. While there I went up to Hanover one day to see some of the boys in the freshman class whom I had known at Meriden. They strongly urged me to apply for admission to the College, saying that President Smith was running a close race with President Stearns of Amherst to see which would secure the larger entrance class, and that if admitted I would at least count one in the contest. The reasoning did not seem to me sound, but as they all agreed that it was possible to secure admission, the argument had great numerical force. I finally reluctantly decided to make the bold attempt. As I walked down the street to call upon the President I felt much as I assume a burglar must feel when he is about to break into a house and secure something which does not belong to him.

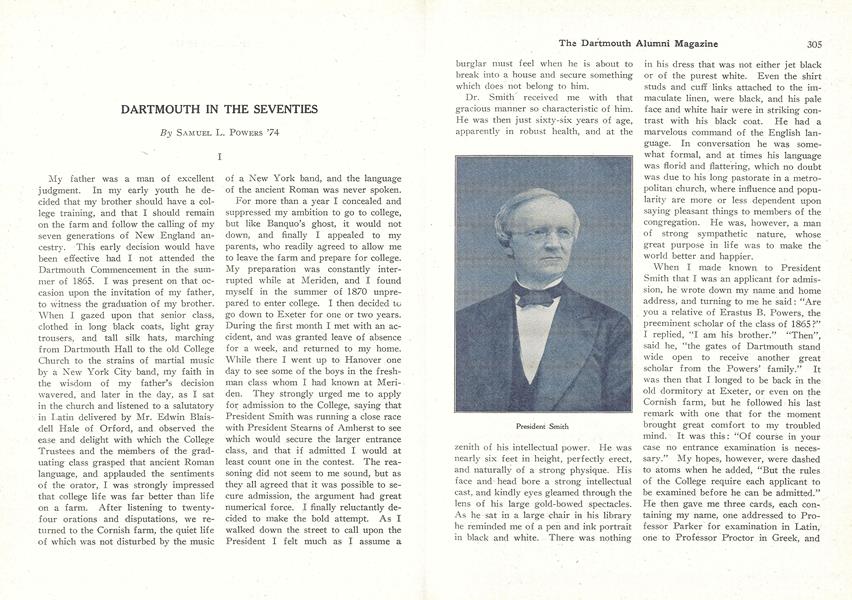

Dr. Smith received me with that gracious manner so characteristic of him. He was then just sixty-six years of age, apparently in robust health, and at the zenith of his intellectual power. He was nearly six feet in height, perfectly erect, and naturally of a strong physique. His face and head bore a strong intellectual cast, and kindly eyes gleamed through the lens of his large gold-bowed spectacles. As he sat in a large chair in his library he reminded me of a pen and ink portrait in black and white. There was nothing in his dress that was not either jet black or of the purest white. Even the shirt studs and cuff links attached to the immaculate linen, were black, and his pale face and white hair were in striking contrast with his black coat. He had a marvelous command of the English language. In conversation he was somewhat formal, and at times his language was florid and flattering, which no doubt was due to his long pastorate in a metropolitan church, where influence and popularity are more or less dependent upon saying pleasant things to members of the congregation. He was, however, a man of strong sympathetic nature, whose great purpose in life was to make the world better and happier.

When I made known to President Smith that I was an applicant for admis- sion, he wrote down my name and home address, and turning to me he said: "Are you a relative of Erastus B. Powers, the preeminent scholar of the class of 1865?" I replied, "I am his brother." "Then", said he, "the gates of Dartmouth stand wide open to receive another great scholar from the Powers' family." It was then that I longed to be back in the old dormitory at Exeter, or even on the Cornish farm, but he followed his last remark with one that for the moment brought great comfort to my troubled mind. It was this: "Of course in your case no entrance examination is necessary." My hopes, however, were dashed to atoms when he added, "But the rules of the College require each applicant to be examined before he can be admitted." He then gave me three cards, each containing my name, one addressed to Professor Parker for examination in Latin, one to Professor Proctor in Greek, and the other to Professor Quimby in mathematics. He instructed me to call upon these gentlemen, who would examine me, and mark the result on the cards, which I was to return to him, and receive my certificate of admission. Even at this late day I am disturbed when I think of those examinations. About the only questions I answered correctly were those to which I gave the answer, "I don't know". Each professor marked his card with a Greek letter, and as I had already learned the Greek alphabet I observed that these letters were near the bottom of the alphabet, which gave them an ominous meaning. On my way back to the President's house my disposition was to tear up these cards and throw the pieces into the hedge, and start back for Exeter, but when I reflected that the cards were college property, and their destruction might constitute a crime which would forever bar me from entering any college, I forebore, and proceeded on my way to see Dr. Smith. When I arrived at his study the sun had gone down behind the Vermont hills, and the President was sitting in the twilight, near the western window, reading a book. I presented the cards, and he arose from his chair, held them up to the light which came through'the window, and a troubled, perplexed expression came over his face. He turned around, secured a match, lighted the large kerosene lamp standing on the centre table, and carefully examined the cards. He then turned to me, and in a rather severe tone of voice said: "Where did you prepare for college?" I replied,i "I never prepared." "You will please be good enough to explain your answer." This I did in a very frank manner, mitigating as far as possible my offense by saying I had acted against my own judgment in yielding to the pressure of my friends in the freshman class. The genial, kindly smile returned to his face, and he stepped over to the southerly window and stood for a moment as though in deep meditation, looking down the valley through which the Connecticut River flows to the south, passing Amherst College on its way to the sea. Then he stepped over to a desk, filled out a certificate of admission, and passing it to me he said, "I congratulate you; you are now a member of the freshman class of Dartmouth College, and I trust your college career will be both pleasant and profitable." My admission was the inauguration of the "selective process" at Dartmouth, and ante-dates that process as adopted by President Hopkins by nearly fifty years.

Of the twenty-one members constituting what was then termed the "Corporation", in 1870, not one now is living. Of the thirty-two members constituting the Faculty, there is how but one survivor. The enrollment of students in all departments numbered four hundred and thirty-six, of which number three hundred and five were in the Academic Department, seventy-seven in the Scientific, forty-four in the Medical, nine in the Agricultural, and one in the Thayer. Of this total number not more than one-third are now living.

Dartmouth at this time could properly have been described as the College of Northern New England. Sixty per cert of the students in the Academic Department came from homes located in New Hampshire and Vermont, and seventy-seven per cent from the New England States. A large per cent were sons of farmers, familiar with labor on the land and in the forests. They were seeking a college training largely on their own initiative, aided by the unselfish and sympathetic sacrifice of hard-working parents of limited means. These boys had carefully thought out the course they were to pursue in life, and entered college with a serious purpose in view. It is probably true that at least ninety per cent of the students at Dartmouth in the early seventies were contributing from their own earnings some part of their college expenses, and in many cases they were contributing the entire expense. Now and then one disappeared from college without saying good-bye to his most intimate friends, and the conclusion was quickly arrived at that his funds had become exhausted. One of the best students in my class disappeared early in the junior year, without saying a word even to his own room-mate. Some months later two of his class-mates were in Boston, and on boarding a street car of the Metropolitan Railway Company they saw their lost member clad in a blue uniform, with brass buttons, serving as conductor and collecting fares. When he came in front of them to take their fares, they exclaimed, with the usual college enthusiasm, "How are you, Dan!" He made no reply, but gave them a stony stare and went about his business of collecting nickels. He was forever through with college and all its associations.

The President was not unmindful of the financial struggle which embarrassed many of his boys, and he bent his energies to secure scholarship aid to lighten their burdens. It would have rejoiced his great heart if he could have secured a scholarship for every student in college, from which an annual income of $60 would have been paid to meet the tuition of the same amount levied by the College. A member of my class decided at the close of the sophomore year to transfer to another college, and called upon President Smith for a letter stating that he was in good and regular standing in the College. The President inquired why he was leaving college. The student, not wishing to hurt his feelings by saying that he was going to another college, asked to be excused from giving the reason. The President said, "Very well", and took a sheet of paper and addressed a letter, "To Whom it may Concern", expressing his regret that so bright a student should find it necessary for any reason to leave college, and predicting that if he were to complete his course a most brilliant future awaited him. He folded this letter and passed it to the student with the remark, "There, sir, you give that letter to your father, and I think it will bring the money." The President could not well understand why any boy should leave Dartmouth while his funds held out. It is quite true that very few at that time did leave for any other reason. The dismissals for misconduct were few, and rarely any for failure in class-room work. In those days a theory was entertained by the administrative officers that however raw, crude or ill-prepared the material presented by the freshman class might be, the educational machine of the College was so constructed and adjusted that it would turn out a finished product of the finest quality at the close of the college course. These were the days when the American college Was wedded to the recitation system. The student was afforded the opportunity three times daily to exhibit how much or how little he knew of the subject under consideration. This exhibition was in the presence of his own classmates, under the cross examination of a well equipped instructor, who did not at all times reveal a sympathetic interest in the witness under examination. Without doubt the recitation system is the best method of instruction ever devised, and is especially well adapted to classes of limited numbers. It is a test in which ambition and pride stimulate the student to do his best work. My belief is that the average boy at Dartmouth in the seventies did about as good class-room work as he was capable of doing. There were two groups in every class who studied very hard—one was at the head of the class, and "the other at the foot; the first was actuated by ambition for high rank, and the latter by pride lest they fall by the wayside. Those in the middle class were inclined to take college life more leisurely, realizing that the pace of the first group was too fast, and that of the latter too slow. The instruction furnished by the College in those days was of the best. The professors were men of learning and long experience, several having grown grey in the service, and three at least had achieved national reputation in their special fields of service. Every member of the Faculty was either a full professor or a tutor. The terms "assistant professor" and "instructor" were unknown in those ancient days.

I can recall vividly my first entrance into a class-room in the fall of 1870. I had entered college late, and the work of the classe's was well underway. The first recitation was in Latin, in Thornton Hall. I had seen Latin teachers in fitting schools, and my idea of a Latin professor was a man well advanced in years, who had grown old in the service. The one I knew at Exeter had taught that ancient language for at least a generation, and the one I had known at Meriden had taught the language for nearly two generations.

As we entered the class-room I saw at the instructors' desk a young man slightly under medium height, with jet black hair, dark eyes, and a clear complexion. This was Tutor John King Lord. He, was then twenty-two years of age. There were men in our class older than he. Just as the college bell finished striking the hour of eleven he picked up a pack of cards containing the names of the twenty-seven men constituting our division, shuffled them with a dexterity that would have done credit to an old poker player, turned them face downward, picked up the first card, and in a clear, resonant voice said "Piatt". In just sixty minutes he called to his feet every man in the division. His questions came with great rapidity, and if the student hesitated, another question followed. His manner of conducting a recitation •was not unlike that which has prevailed for many years at West Point and Annapolis. It created a military atmosphere in the class-room, and riveted the attention of every one on the lesson of the day. Tutor Lord was very popular with the boys in the early seventies. He played no favorites, exhibited no personal likes or dislikes. Every man received treatment according to his deserts. Professor Lord is now the sole survivor of the Dartmouth Faculty of 1870, and cannot fail to be conscious of the fact that he will always retain the affection and high regard of all students who came under his influence in the early days when he was entering upon his long and distinguished career as a member of the college Faculty.

Charles Franklin Emerson, who graduated in 1868 in the same class with Professor Lord, was Tutor in Mathematics in the early seventies. " He was an excellent teacher, indicating at all times his friendly interest in his students. It was a fatherly interest, quite resembling that of the father toward his son. He appeared to grieve when the boys did poor or indifferent work, and he chided them and assumed as serious an attitude toward them as he was capable of. All this was a part of his nature, and throughout his entire life he never lost interest in the thousands of students with whom he had come in contact while connected with the College. As they went forth into the world to engage in the struggle of life his interest in them never flagged, and he rejoiced in their success and grieved over their He exercised a wholesome and helpful influence upon the entire student body.

Dean Emerson possessed in a most remarkable degree the faculty of recalling faces and names of the alumni when after years they returned for the first time to the old college town. Many a graduate after an absence of twenty or more years has been surprised that his gray beard and bald pate failed to disguise him as he received the cordial greetings of the Dean, who was a tutor at the time of his graduation.

Charles Parker Chase, a graduate of the class of 1869, was tutor in Greek in 1870. My preparation in Greek was so limited that I hesitate to express any opinion of his merits as a teacher. I recall, however, quite vividly that he and I were not always in accord as to the correct translation of certain Greek passages, and frequently my answers to questions relating to the construction of that ancient language did not receive his hearty approval. I never have made any effort to determine whether I was right or wrong, but after a lapse of more than fifty years I am disposed to give to the tutor the benefit of the doubt, and confess that he was right and I was wrong. During the year that I was under his instruction

there occurred one incident that has remained fixed in my memory. One morning Tutor Chase turned suddenly away from translation and grammar and started an inquiry as to the location of certain geographical places. As we were engaged in the study of Greek there was a fair presumption that these places were either in Greece or in localities adjacent to it. The two students preceding me answered by saying, "An island in the Aegean Sea", and the answers were correct; then he called me, and asked me the locality, of a certain place. I assumed we still were in the Aegean Sea. No warning had come to any of us that we had left those beautiful islands, and were exploring a distant country far removed from the waters surrounding Greece; so I answered promptly, "A small island in the southeastern part of the Aegean Sea", to which answer the Tutor remarked, "A large town in the northern part of Italy. Sit down." That incident amused the class immensely, ana has been my constant companion ever since. It did more to introduce me to the American public than any other act of my life. The story preceded me everywhere. It was awaiting me in Washington upon my arrival; I found it well installed in Chicago, and even in San Francisco; no doubt among Dartmouth men it will outlive the last survivor of the class of 1874. While the answer I gave was not correct I still maintain it was justified under all the circumstances.

Professor Chase was a most loyal son of Dartmouth, and rendered service of great value while treasurer of the College. He possessed a charm of manner that was most attractive, and preserved the spirit and appearance of youth to the very close of life.

(To be Continued)

President Smith

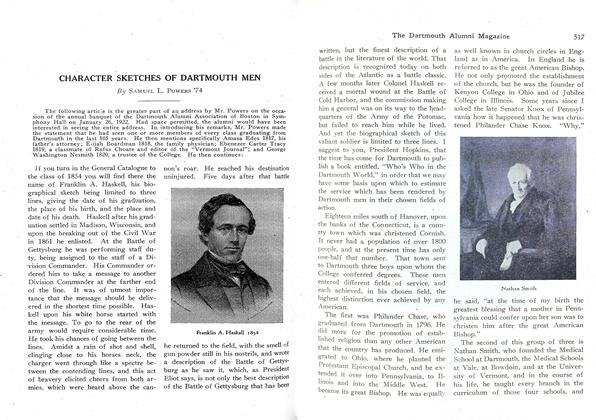

John K. Lord, as a tutor

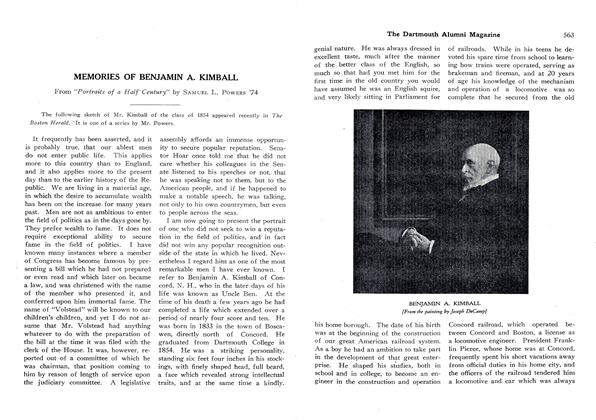

Charles F. Emerson in the early seventies

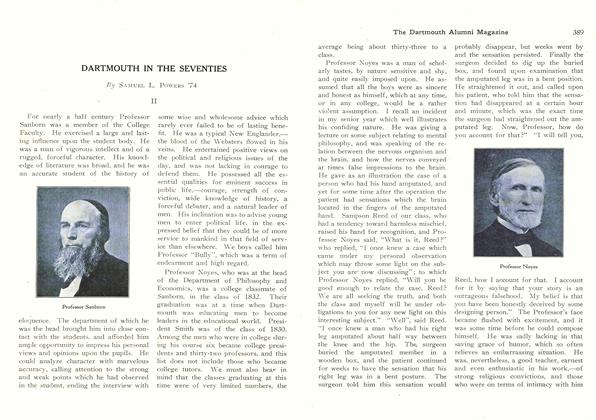

Charles P. Chase as his first classes knew him

The 1923 Cross Country team, one of the best of recent years in Hanover

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhatever be the time selected

February 1924 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH JOTTINGS OF A SOMEWHAT DESULTORY READER

February 1924 By Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Class Notes

Class Notes$1000 REWARD PEARL NECKLACE

February 1924 -

Article

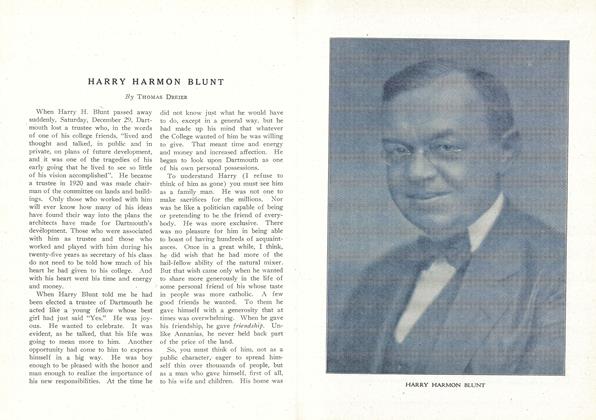

ArticleHARRY HARMON BLUNT

February 1924 By Thomas Dreier -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

February 1924 By H. Clifford Bean