A mystery begins at Tke scene of the crime.

The usual suspects fill the bookshelves in George Demko's Fairchild Hall office. Tomes on Russian political history and planned communities in Eastern Europe squeeze against volumes of population statistics. Demko teaches geography, after all, and specializes in those areas. But crammed in with the academic texts are stacks of paperback crime novels, books on mystery writing, murder anthologies, crime fiction, and bibliographies. "I've always loved mysteries," says the geography professor. "I've decided, in my old age, to take my hobby and combine it with my profession."

Demko teaches a popular freshman seminar called "Landscapes ofMurder." The course traces the history of the detective story across time and across cultures, paying special attention to how the genre reflects cultural, social, and physical geography. "The books in the course are all excellent geography," says Demko. "They transport you. They tell you exactly what's going on in a particular area." He argues that good mystery writing is better than travel guides for giving a sense of a place. "I can promise you this," he says. "If you're going to New Orleans, I'll give you a James Lee Burke mystery to read, and you'll learn more about New Orleans from that mystery than you would from a travel book. It will be cheaper. And it will be more interesting."

According to Demko, the best American crime writers started out as regional writers. Writing for a regional audience, they had to get the details of their landscapes right. A lot of them, in fact, use an intimate knowledge of place to help solve their crimes. The detective in Philip Craig's mysteries, set on Martha's Vineyard, often relies on his knowledge of the local tides to solve his cases. Nevada Barr's mysteries, set in various American national parks, turn on her ranger's knowledge of those places. "Novels create environments," says Demko. "Mystery literature, particularly in this country, starts with reality. There is strict order. Then somebody kills somebody—disorder. Detective comes, sets everything in order again. You can't understand the disorder until you understand the order of the society—that's why mysteries pay such good attention to place. They have to, or else they wouldn't work."

An important goal of Demko's seminar is exposing students to the wealth of crime fiction outside the United States. The detective story genre began formally with Edgar Allan Poe's "Murders in the Rue Morgue" in 1841, then spread rapidly to Europe, Asia, and other parts of the world, each culture shaping and redefining the form, style, and underlying messages. For example, Demko says that in Latin America, the genre is upside-down. Whereas U.S. detective stories reflect our concern with maintaining a stable, ordered society, Latin American crime fiction is a political protest literature, anti-authority, anti-state. "The bad guy is usually the state or local government," says Demko. "The good guy is either a detective or a common citizen who fights against the state to protect the oppressed. He ends up being shot, or jailed—or the mystery goes unsolved. As opposed to the order-disorder-order structure found in most American mysteries, Latin American structure moves from oppression to a failure to set society in order. There's no neat resolution. It's very negative stuff."

Demko loves uncovering the cultural geography embedded in mysteries from around the world. In Eastern Europe he doesn't find glamorous cities and elite detectives like Sherlock Holmes. Instead, says Demko, "Mysteries are set in villages. The detective is typically a plodding village policeman. The characters are everyday people. Often, especially while communism took hold, the mystery becomes a vehicle for the state fighting evil capitalists." He points out the differences in Japan, a less violent, non-gun society. "Honor, revenge, and saving face become a big part of the literature there, along with a more spiritual element than you'd find in the United States. Americans tend to find the reading a little slow, probably because it's more thoughtful than what we're used to."

American crime fiction, though, says Demko, has come a long way from the dames and the booze of Raymond Chandler's Los Angeles. He talks about Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and Mickey Spillane as American icons who were important in defining just one kind of mystery: the hard-boiled. "But I don't think they were great writers," says Demko. "Chandler did a good job of evoking L.A. culture, but a lot of what those guys wrote was just dreadful, just blood, guts, and sex. In terms of geographical writers, there are much better people today writing about those same places."

Demko says we are in the "flowering period" of the genre. "All those old rules that said you had to have a 'hard-boiled,' a 'cozy,' a 'locked-room' are gone," he says. "Thank God. Today, the mystery is probably the most flexible genre that exists. The genre frequently merges intO science fiction, Gothic, and espionage. Women dominate the genre nowthere's a whole slew of smart, tough girl detectives. You can find social movements in the genre, causes like the environmental movement, like the anti-homophobic movement. It's all great geography. When you read Dana Stabenow's mysteries in Alaska, where her detective is an Aleut, you read not only about environmental degradation, but about the loss of culture, the loss of sacred places. She can get at nuances that you can't get in a strict academic accounting. And you know what? There's a huge audience out there for it. It's really very powerful."

In fact, no genre is bigger. One out of every four books sold in this country is a mystery—40 percent of all the published fiction. "Yetit's a demeaned genre," says Demko. In the seminar, he tries to correct that image. He talks about the "literarygreats." Mark Twain wrote mysteries. William Faulkner. Graham Greene. Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine poet and intellectual, wrote superb mysteries and edited a mystery magazine. "And there are remarkably literate mystery writers today," he says. "Those are the people I want to expose my students to."

people I want to expose my students to." Is Demko writing any mysteries? For now he is content to write about them, including in his regular column, "Atlas of Crime," for the journal The Armchair Detective. His book, Landscapes of Murder, is due out this year.

JIM COLLINS is a contributing editor of thismagazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

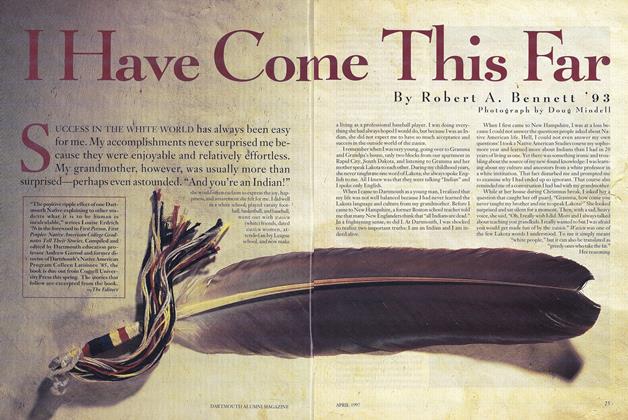

Cover StoryI Have Come This Far

April 1997 By Robert A. Bennett '93 -

Feature

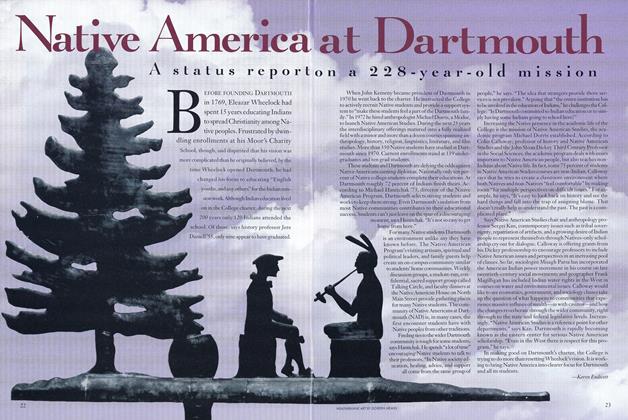

FeatureNative America at Dartmouth

April 1997 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

April 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

April 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

April 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe Are Not Your Indians

April 1997 By Arvo Mikkanen '83

Jim Collins '84

-

Article

ArticleBaseball and the Pursuit of Innocence

June 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Role of an Intellectual

JANUARY 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

Jul/Aug 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryANDREW WEIBRECHT '09

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

FEATURES

FEATURESA Monk’s Journey

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84

Article

-

Article

ArticleReport of the Alumni Fund Committee

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleNomination of Trustee

January 1948 -

Article

ArticleThe Classic College

APRIL 1991 -

Article

ArticleTrailrunning 101

July/Aug 2002 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1957 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

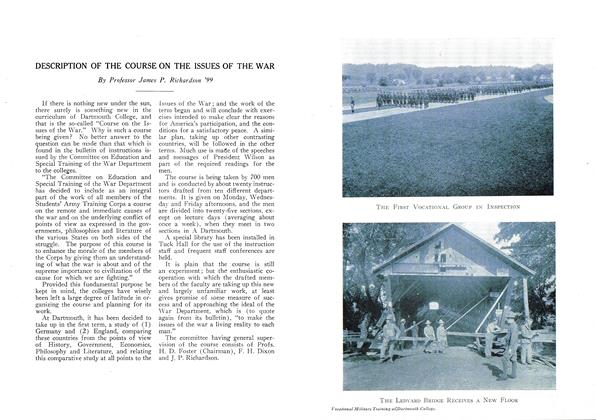

ArticleDESCRIPTION OF THE COURSE ON THE ISSUES OF THE WAR

November 1918 By James P. Richardson '99