The average age at which students enter college is about 18 years 6 months. There is always a certain, rather small, percentage who enter considerably younger than the average. They range all the way down to a little under 16 years of age. The number of these younger men is getting larger year by year.

Recently there has been a good deal of discussion, chiefly among college presidents, dents, as to the advisability of having students begin their college work very much under the present average age. Some presidents argue that men should be encouraged to begin their college career at the age of 17 or less. They maintain that students who enter young stand higher in scholarship as a rule than do the older ones and that the long preparation commercial careers tends to force men to begin their life work too late. They believe that in some way the secondary school preparation should be speeded up.

The demands of the professional schools and of business are gradually being extended. In some instances the length of the professional course has increased and in the majority of cases there is greater insistence upon a long preliminary academic training. Business, too, has taken on more of a professional character. Its technique has improved, its content in actual knowledge enlarged and its demand for more thorough and more intensive non-professional preparation is insistent.

Those who argue against early entrance to college base their opinion almost exclusively upon the belief that those under- graduates who are below the average in age do not gain what they might gain in the way of social and personal development. It is claimed that the youngest students for the most part lose decidedly in the matter of fellowship and participation in the varied life of (an undergraduate body.

In view of this discussion President Hopkins has asked that the history of the men who had entered Dartmouth at an early age be compiled. He knew that the many questions involved demanded more than a theoretical discussion and that an opinion should be based only upon discoverable facts. For the purpose of this study he chose the men who had entered the classes of 1901 to 1922 under 17 years of age.

Mr. Conant, Assistant to the Dean, prepared a systematic statement of the age, the scholarship standing and the student activities of each of the younger men who entered in these classes. This included both those who received degrees and those who did not. The record was then turned over to this office for analysis.

Obviously there are two parts to any such discussion. One should know the history of these men while they were undergraduates and should learn as much of their subsequent careers as may be possible. The first part of this inquiry is comparatively easy; the second part is extremely difficult. For the present only the undergraduate history of the younger men of the twenty-two classes under consideration will be discussed.

The total number under 17 years of age who entered college in the twenty-two two classes was 224, of whom 167 received degrees. A review of the group will be made from the standpoints of scholarship, mental alertness, preparatory schools, student activities, social development and entrance upon graduate study.

From the standpoint of scholarship the younger group is conspicuous. In the first place the losses out of the group by failure, withdrawal and other causes are very small. There were only about 25% of them who failed to get degrees, while the normal loss in one class after another seems to be approximately 45%.

In the percentage of those taking honor rank the group stands remarkably high. Out of 224 in the group there were 54 who received honors, or almost 25% of the total. It is difficult to make a comclasses parison with any of the recent graduating because the interruption caused by the war has undoubtedly upset any scheme of statistics that might normally be applicable. It seems best, therefore, to compare this total group with the class graduating just as we entered the war. In the Class of 1917 there were 38 who received honors. This is a little less than 10% of the total number who entered with that class. The contrast of 10% with 25% is very significant.

More than 16% of the younger group received Phi Beta Kappa standing. The class of 1917 had about 6% of Phi Beta Kappa men.

The percentages given for those who took high rank seem to be merely the same kind of percentages that might be made provided the whole group of younger men were compared with the total who entered college. It would be a long and very laborious undertaking to discover whether this is true or not, but an examination of the standing at graduation of each of the 167 men who did graduate seems to show that on the average their rank was higher than that of others in their classes.

It is a common statement that those men who enter college younger than the average have made greater progress in their school work because they are the brighter boys. Until the last two or three years such a statement could be based only on general impression. There was no evidence to prove it. At present we give a Mental Alertness Test to all freshmen and this test appears in a general way to distinguish the men of the class on the basis of their acquired information, their accuracy, their quickness of perception and to some degree on their reasoning power. After students have taken their Mental Alertness Test the class is distributed into five groups according to their performance on the test. We believe that the tests given to the classes of 1925 and 1926 are rather better adapted to distinguish between men than were the tests given to earlier classes. In these two classes there was 68 who were under 17 years of age when they entered college. In the highest group on the basis of the Mental Alertness Test, called Group 1, there were twenty-six members of these two classes, in Group 2 eighteen, Group 3 ten, Group 4 twelve and in Group 5 two. If this showing is typical of all classes, the opinion of those who have believed that the men who entered college at an early age were on the whole unusually alert mentally seems to be substantiated.

It is sometimes said that the younger men are those who have had a better preparation for college work. This would be true provided it could be proved that they come from better preparatory schools than others do. The fact, however, is that the schools from which the younger men have come since the entrance of the class of 1901 were of all sizes and all degrees of reputation. There is no distinction to be made between these schools and the schools at which other men were prepared. The rapid progress of this group of students would seem to depend upon their own ability or their industry rather than upon a special quality of teaching or upon especially good school facilities.

The objection most frequently raised to early entrance to college is that the younger men get less out of college life than do those who enter at the average or above the average age. This is an extremely difficult point to handle. One can illustrate the degree to which they participate in the life of the college by trying to find out how much they have engaged in student activities, what percentage were accepted into fraternities and any other incidental evidence that may be gathered.

Of the 224 members of the younger men 65 are recorded as having engaged in organized student activities. This amounts to 22.4% of the total number. In ath- letics there were 17 who achieved some success, 9 obtained organization managerships, 23 were connected with col- lege publications, 3 took part in dramatics, 11 belonged to musical organizations. These figures are probably inadequate since the only records available are those given in the Aegis. In the preparation of class records for publication in the Aegis the material is furnished by the men themselves. The modest man may not give a full account of himself, another type of man may overstress his achievements. Moreover one cannot tell from the Aegis just how long or how arduously the men were engaged in the organizations with which they specify that they were connected.

For these reasons no percentage comparison should be made, but it certainly seems to be the case that the activity of the younger men in college organizations was smaller than that of the average of the class. This is particularly true of athletics. The younger men appear to have obtained their full measure of managerships and to have had an unusually large connection with the college publications. The showing on this point is the spot in which the younger group is deficient. It is evident, however, that their tendency as a group was to take part in those student activities that were literary and intellectual in character rather than athletic.

There may be a wide variance in opinion regarding the social position or social development of the unusually young men. This is not the place for a full discussion of the subject. It is appropriate, only to state certain facts that bear upon the problem and suggest ways in which the discussion might then proceed.

There is an interesting saying among undergraduates that students with a big preparatory school reputation seldom retain that reputation through their college course. It seems that the vital factor here is precisely this matter of age. One notices in each succeeding freshman class that the older members are the leaders and that it is from these older members that the majority of class officers are chosen. The distinction in age is less significant as a class advances toward graduation. In senior year it seems to be the case that the men of average or less than average age have overtaken the older men, hold the major part of the class offices and take their place distinctly in leadership of class opinion.

Another piece of evidence as to the social qualifications of students may be illustrated by admission to fraternities. In the twenty-two classes under discussion there were 167 men under 17 years of age at entrance who remained in collage and received degrees. Out of these there were 102 who were admitted to fraternities, while 65 were not. This means that practically two-thirds of the very young men became fraternity men. No effort has been made to make a complete comparison for all of the twenty-two classes, from 1901 .to 1922, but three classes have been chosen at equal intervals throughout that period. These are the classes of 1902, 1912 and 1922. In the class of 1902 there were 69 fraternity men and 62 non-fraternity men. In the class of 1912 there were 115 who joined fraternities and 97 who did not. In the class of 1922 there were 180 fraternity men and 49 non-fraternity men. In the three classes the total number of fraternity men was 364, while 208 were not taken into fraternities. That is to say, slightly less than 64% of the members of these three classes entered fraternities. If these three classes may be regarded as typical of the twenty-two classes in succession it would seem that the younger men were fully up to the average of their classes, provided admission to fraternities may be taken as evidence of social success.

So much for the facts that are obtainable regarding the success of the younger men among their fellows. Several interesting problems are presented. One is at liberty to maintain that those who enter college at the age of 18 or more have wasted one or two years. They may have had interests other than those connected with their preparatory school course, or they may be less intellectually inclined. For these reasons and for other reasons they have lagged behind instead of maintaining the normal rate of progress. Again one might speculate as to the social condition of a college if the majority of students entered at the age of 17 or less. It would probably make a considerable difference in the efficiency of athletic teams and of various college organizations, it might even lower the standard of college -publications, although that is doubtful when one remem- bers how many of the younger men have in the past been on editorial boards, and even editors-in-chief. One may also wonder who would be the leaders of college opinion provided the younger and very bright men were not overshadowed as they are today by their older classmates. In fact there is room for much debate as to the whole undergraduate life of a college provided all students in high school; could be speeded up to the pace now set by those below the average in age.

There is one further point concerning the younger men that is deserving of attention. They evidently maintain their strong intellectual interests beyond the time of their graduation from college. This is proved by the fact that out of the 167 who graduated from the twenty-two two classes there were 77 who entered graduate schools in order to prepare themselves for professions or occupations demanding additional study. The nature of their graduate study is of all types including engineering, chemistry, law, medicine, ministry, teaching and commerce. It may be mentioned that one of them became a Rhodes Scholar and another after a short period spent in teaching obtained a rather prominent position in one of the foundations for the advancement of scholarship. In the class of 1922 about 30% have entered graduate schools for one purpose or another. This may be contrasted with the 46% of the younger men under consideration. eration.

A study of this kind is incomplete and inconclusive without the additional history of these same men since graduation. In order to determine the total degree of their success it would be necessary to follow them after graduation and make a comparison between their accomplishment and that of their older classmates. Records are not yet available to make this study with the thoroughness that would enable us to draw satisfactory conclusions. Material will be accumulated gradually and the study completed at an early date.

The head of the procession

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleCommencement is over. The college year is ended.

August 1923 -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1923

August 1923 By WILLIAM H. MCCARTER, 1919 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1923 By P.E. WHELDEN -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1923 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

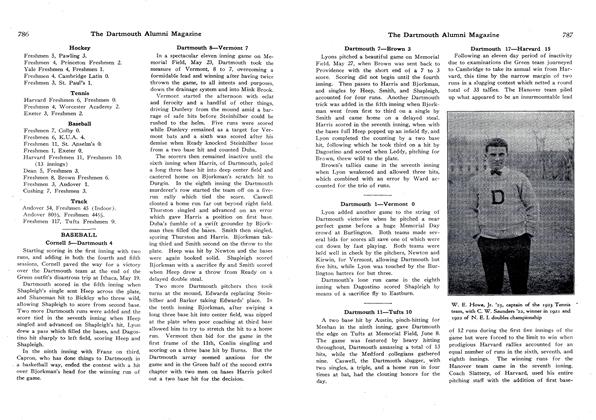

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

August 1923