Another class has gone away from Hanover and now takes part in the great body of Dartmouth alumni. All over the country the colleges have sent forth their armies of youth to enter upon tasks for which, hopefully, their studies and experiences, social, athletic and academic, have sought to fit them. That most have been fitted for them is a reasonable belief. That a few have missed the goal is a certainty. But that the colleges of the country are regarded as amply justifying their existence is to be presumed from the fact that as the years unfold the number clamoring for higher education steadily increases. The verdict of the country is unmistakable. It approves of the colleges and does so on the basis of their work.

The tendency, we believe, is toward the admission that a liberal education and a technical education must be to a great degree gree separate and distinct; that is to say, that the average college course is properly to be regarded as a general fitting for the use of the mind and for the appreciation of the things of the spirit, where the professional school is to foster the technical skill required for individual service in the chosen field of gainful activity. We would respectfully suggest, especially to parents whose sons are about to enter college or are now in under-classes, the idea that the liberal education should remain unembarrassed, as far as possible, by eagerness to anticipate professional training.

Beyond doubt it is possible by the judicious use of the elective system in the junior and senior years to bend the student's mind toward those directions in which his postgraduate studies will also lie. But it so often happens that the undergraduate is undecided in his aims, and it is furthermore so true that the broader education bears so importantly on the usefulness of the future citizen, that we question the desirability of beginning the process too early, or stressing it too powerfully. Not for nothing have many law and medical schools of recent years limited their entering classes to men who could present an A.B. degree, or something very nearly equivalent thereto. Pretty nearly everything that can go to the making of a bachelor of arts is serviceable to the man who will later acquire the technical learning of a doctor, a lawyer, a clergyman, an engineer.

There are things in life other than the making of a success in one's chosen line of work. Education has to fit one for those things, as well as for the winning of bread. One who is so fortunate as to add to his purely professional knowledge some of the graces of a general culture gets much more from his career on earth than otherwise he would obtain. It is a most deplorable mistake to specialize too soon, partly because it is often ineffectual specialization and partly because it is narrowing. The student may adopt some totally different life work from that which in his earlier college days he contemplates; but even if he does not and remains steadfast in his purpose, it is very certain that his immature attempts to give to his studies a professional cast will hamper his development and best success as a professional man. To seek first the kingdom of intellectual breadth is a very sensible commandment.

We have been moved to this rambling discourse by a very excellent and timely editorial in the issue of the Daily Dartmouth for May 24, under the caption, "Bread, Butter and Majors," in which the editors advise strongly against exalting bread and butter above the general cultivation of the mind—because to do so "is to court ultimate and emphatic dissatisfaction." Only to a limited degree and late in one's course can much be done in the way of forcing electives to serve professional ends.

Meantime what is the college really trying to do ? Innumerable efforts to specify its aims have been made and it has seemed that of the making of formulas there was no end; but it happens that as we turn the page before us the eye falls on a very pungent summary of the underlying idea which should be widely heralded—and as so often happens it turns out that the appropriate word is said by that very sensible and pragmatical idealist, the president of Dartmouth college.

With that terseness and that directness which seem to us his most notable characteristics when speaking of educational problems, President Hopkins not long ago told the conference of New Hampshire's Congregational churches that the task of education at present was "not so much to teach the student what to think as to teach him how to think." There is a serious danger in trying to do the former, in that even contemporary opinions vary as to what the truth is, and differ so widely at divers times that the instructor of youth must assume altogether too much if he attempts to teach what to think, save within very narrow bounds.

" 'What is truth?' asked jesting Pilate" if, indeed, he were jesting. Who shall answer this,ancient and still unsatisfied query ? Neither the reactionary nor the liberal, with any dogmatic certitude. Dr. Hopkins defined truth as "the conformity of our belief to reality" which suffices as a definition of truth without identifying reality itself. The things we are sure of—sufficiently sure of to remain convinced for centuries—are distressingly few. Those few constitute the only matters in which it is at all safe for education to dogmatize—the bench-marks on which reliance may be placed; for one really must start with something tangible in the way of facts, and all that can be asked is a reasonable assurance that they are really facts. Starting with them, one may seek for other truth. But the major task of education must necessarily be to equip the seeker for his quest, rather than satisfy him with a grail already found.

Much of the discussion which has waxed so bitter of recent years around the topic of academic freedom seems to have concerned itself with mistakes as to means and ends. There has been rather too much insistence on what was supposed to be truth itself, and too little on openness of mind to seek out the truth. There has been a certain bigotry on both sides—an assumption that either the old or the new was necessarily true, or necessarily false, according to the prejudices of the protagonist. If only the sterling principle enunciated by the president can be more widely heeded, it may be that there will be less of friction between liberal and conservative. To be free to seek the truth—yes. To be free to proclaim that to be truth which is open to a serious doubt—no.

Nevertheless there is need for some caution in disregarding the teachings of past human experience. There are doubtless less more things in heaven arid earth than are dreamed of in any present philosophy, and yet this does not necessarily imply that all present philosophy is a sham, on the eve of being outlawed by a future revelation. Not everything which the present accepts as truth is necessarily a lie. All one can say is that so many once-accepted truths have dissolved before the growing light of man's intellectual development that one is chary of accepting anything as immutable—save such things as obdurately withstand political, moral, or social erosion. That man is best educated who best knows how to estimate the worth of things natural and spiritual, whose mind is most supple and best equipped for its incessant tasks.

To teach young men how to think rather than what concrete things to think puts in a nutshell the great problem of the schools. It is a sentence worthy to add to certain others struck off President Hopkins's official anvil. Like all generalizations it is easily open to misconception—possibly open to misuse, as nearly all formulas are—but nevertheless most serviceable as a true fingerpost on the road. What has been regarded as truth in the past may with a few years become interesting rather than important. What is regarded as truth now, and what will be regarded as truth in the future, may in due season become less important than interesting, too. All the time the vital need is for intellectual alertness, tempered by common sense, to judge the probabilities as they come along and estimate, at their apparent worth, both the old and the new in human experience. "To have an appetite for the truth" was one of the pithy expressions used. To have an instinct for it might be another—albeit such a thing must to some degree be innate rather than a development from without.

Whatever ministers to the usefulness of the mind is proper material to employ in the process of education. We have evidently passed out of the age when education was supposed to mean stuffing the youthful mind with predigested facts and into an age when it is seen to be more important to make efficient the machinery whereby a man thinks. It is possible that in the shift we may underrate the office performed by bald memorizing, just as in the past it was so commonly overrated. The older colleges had their era of worshipping much too fervently at the classic shrines; the colleges of today are byway of worshipping too fervently somewhere else. We are still concerned with what men have thought in the past just as surely as we are concerned with what they are beginning to think for the future. We are a part of all that we have met. We cannot ignore our heritage. But it is a patrimony which we are not to squander as if it were all-sufficient; it is to be invested and developed, like the ten talents in the parable. The colleges are not custodians of truth, so much as custodians of its germ and nurseries for its propagation.

Out of the thousands of young men who are annually graduated by our colleges and universities, probably a very few have been started on the road to being expert thinkers-out of new truths or rather of old truths about to be newly revealed. It can hardly be otherwise. But it is the hope that of those thous ands the vast majority will go forth at least with an eagerness and an "appetite for truth", as well as with a better understanding to know the truth when it does appear under the magic of the few who are gifted in its revelation. The colleges have no choice. Their task is clear. It is to teach young men and young women "how to think, rather than what to think". It is not even their province to teach them what not to think, since a good rule works both ways. It is to teach them, by whatever means seem well adapted to that end, to use with address the minds implanted in them, with sufficient knowledge of what humanity has thus far done, with sufficient reverence for past human experience—but with full knowledge that finality is hardly to be predicated of anything under the sun. Moreover, as Dr. Hopkins aptly said, we can hope to do little more than "take a small dimension of the truth and master it" in the period of our schooling. But in the mastery of it, such as it is, we may hopefully obtain that which will serve when it comes to solving future riddles. The mathematician's formula is intended for application to data not yet discovered. The musician's training is designed, not merely to enable him to play music which he has painfully memorized, but also to read great music yet unwritten.

That the process of democratizing the government of American colleges is only partially accomplished by increasing the powers of the alumni through their representation on the boards of trustees and will eventually be extended by including greater powers for faculty, students and even the general community in matters of administration, appears to be the suggestion of President McCracken of Vassar in an article in the July issue of the Yale Review.

Admittedly the colleges are at present mainly in the process of increasing the scope of alumni representation; but this has been going forward rapidly with in the past two decades and at the moment it is probable that in most American institutions of the higher learning the alumni proportion of trustees will average nearly a third—being much more than that in many cases. The suggestion that this by no means represents the final development is interesting. Dr. McCracken appears to believe that the next step will be the extension of a more potent franchise than is at present usually enjoyed by professors and even students in matters of university control, especially stressing the possibility of making the college presidency a matter of faculty choice, on the theory of its being an office mainly concerned with matters of instruction, as a sort of chief executive of the faculty—leaving the matter of extraneous administration to other hands.

Whether or not this quite accurately states President McCracken's contention, now that we have written it, is perhaps doubtful—but it at least embodies the impression we have derived from a reading of his article. Still more doubt besets us as to the ways in which students and more especially the community are to be made very important participants in the government of colleges. The reasons for the steady and increasing growth of alumni power are easy enough to see; and it is certainly desirable that the professor, being on the ground as well as alertly interested, should not be entirely devoid of voice in college affairs apart from the voice which he may have as himself an alumnus (which very often he is, although by no means always.) Alumni representation sprang up because of a natural demand for control on the part of those who are constantly called upon for money to help run the institution. The professors' claim to be considered also has much about it which is natural, whatever may be the current opinion of its feasibility or the current idea of the extent to which it can be carried. ried. Something no doubt, though not too much, can be' spelled out of student government and the student disciplinary apparatus as indicating a trend toward a more direct participation in the college government. Nevertheless we should hastily append a conviction that these predicted growths should be left to make their way by the slow natural erosions due to natural causes and developments, as alumni participation has done. The world, including the collegiate world, will be much safer for democracy if democracy is not hastened into tasks which may be beyond its strength, or into tasks which are not appropriately to be over-democratized.

Believers in democracy are prone, one fears, to overdo their zeal and to be somewhat too sweeping in their edicts declaring every doubter anathema. The virtues of democracy are great, rather than of universal application to every conceivable situation that may arise in the development of government, whether political, social, or educational. It is obvious that what is now in process—to wit, the democratization involved in enlarging the alumni functions in the direction of college management—has been a distinct improvement over the ecclesiastical autocracies of old time. It is less obvious that the same process can go on always without stint or limit to work even greater benefits. One prefers to ponder this a little, sagely suspecting that democracy when limited in its scope is more workable and more enduring than an unfettered exercise would be, and desiring not to exceed speed limits in embracing new ideas—although in no sense denying the possibility of their worth. "Festina lento" is a formula the wisdom of which usually exceeds its popularity.

It it no doubt widely and justly believed to be heretical to deny the virtues of democracy in the abstract—but there is growing up a most unmistakable tendency to question the wisdom of democratic excesses in the concrete, without thereby incurring the condemnations due the heresiarch. That the cure for the shortcomings of democracy is "more democracy" has come to be doubted, or at least to be regarded as requiring occasional distinctions. It does not necessarily follow that the suggestions of Dr. McCracken exceed either probability or desirability—but only that they deserve to be thoughtfully weighed without the advantages or handicaps of unjustifiable presumptions, for or against.

A pertinent commentary on the theory of Dr. McCracken was offered in the unfortunate developments at Amherst College at the recent Commencement, ent, where student opinion was distinctly divided on a matter affecting the college policy. True, the originally predicied dicted "students' strike" did not take place in anything like the magnitude which newspaper reports tended to forecast; indeed in view of the outcome it may even be claimed by those who take Dr. McCracken's view that material evidence was afforded as to its essential soundness. Our feeling remains one of hesitation with respect to making student opinion a regular factor by a comprehensive extension of undergraduate control, chiefly because of the dangers due to immaturity, inexperience and the generous, but not always justified, enthusiasms of such. In the Amherst case the last analysis showed only a baker's dozen of the graduating class adopting the tactics of forthright rebellion in response to a warm-hearted rather than cool-headed sympathy, which may well be reassuring. But to make the educational policies of the average university, or the filling of its presidency or the various professorships, depend too much on undergraduate whim still appears to us a dubious course. It is not that students, because youthful and inexperienced, would be necessarily and always wrong but at least it may be said that there is no presumption they would be necessarily and always right. The presumption, if any exists, favors the wisdom of experience ence rather than the warm-blooded sympathies of younger men easily swayed to a personal partisanship on grounds which, as maturer alumni, they will very possibly reject.

A word as to rather a delicate matter, which nevertheless appears to be bulking rather large in the view of Dartmouth alumni with sons about to seek a college career. The natural and traditional course for any Dartmouth man is to send his son to Dartmouth—a course seldom dom deviated from save for compelling reasons in exceptional instances. It is increasingly a problem, however, with such because of the growing belief that to be a "legacy," as the student body commonly calls a lad whose parents and brothers have been of the same college, imposes a sort of artificial and additional handicap, not only by failing to tell in a boy's favor, but also by raising a sort of hostile presumption against him. The obvious remark is that certainly a newcomer should face the situation on his own merits and ask nothing in the way of favor because of precedent relations. Most would agree heartily to that. The objection which we have heard raised, not only by our own alumni but also by alumni similarly situated in other college groups, is that the actual merits of a "legacy" do not invariably command the recognition they would get if the entrant were not a "legacy." In other words, possession of fathers and brothers may actually be treated as telling against a man who otherwise would be more cordially estimated.

How to deal with a sentiment of that kind is likely to tax one's ingenuity. It is plainly the opposite extreme to that which accords undue weight to family history. It represents a collision with Charybdis in the process of clawing frantically away from Scylla. The middle course, which gives every boy, even if his family have been Dartmouth men be fore him, as fair a chance at the good things of life as others get who are less abundantly provided in this way, is not an easy one to steer. Moreover one has to make due allowance for parental bias, as well as for bias in the undergraduate. It is apparent, however, from chance comments that a very real situation is growing up which may have the unwelcome effect of causing the sons of alumni in our own and other colleges to seek education in colleges where there can be no question of any "legacy" at all. The subject is mentioned with some hesitancy and yet the editors feel that it is better on the whole to face the matter with candor and frankness instead of letting concealment feed like a worm in the bud.

Much wisdom is invariably and traditionally uncorked' at Commencement time by the graduating classes all over the land, which elders are prone to treat with a pitying smile but which occasionally merits a sober thought. After all, the young are those to whom we must look for most of our progress. For example it was remarked by a class-day orator at Hanover that there might be need of taking what the courts call a distinction when one urges that the men of Dartmouth "set a watch lest the old traditions fail," to the end that we set no watch save to safeguard against failure the traditions worthy to survive. There is always the chance that a tradition, once virtuous, may be outlawed and deserve little reverence in a new condition of affairs.

Unfortunately it is not invariably true that men agree on such matters; and it is further very generally the fact that no court of last resort can be erected to which to submit such moot matters on appeal. Fortunately, as the editors of this MAGAZINE see it, there is no great prospect of immediate questioning as to the validity of the Dartmouth traditions which the poet had in mind when he wrote. There is, however, increasing need for the setting of the watch because the amazing growth of the college in point of mere size in itself works against the traditions one associates with the small college and its essential democracy of life.

It would bother almost any one, even if to the manner born, to crysallize in words what we vaguely feel to be meant by the Dartmouth tradition. Our feeling, however, is that very few would say that their vague conception was of anything which age could wither or custom stale. Every college has an elusive thing which it usually refers to as its ''spirit" and which is as unmistakably individual as the soul of the human being. We must doubt that there is a serious danger of Dartmouth's preserving to her own hurt anything in the way of tradition handed down from a simpler and more restricted past. The applications will vary. The tradition endures.

The Lock Step of 1920

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE REJOINDER OF JOAN

August 1923 By EDWIN J. BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1923

August 1923 By WILLIAM H. MCCARTER, 1919 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE STUDENTS AND THE AVERAGE AGE

August 1923 By RICHARD WELLINGTON HUSBAND -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

August 1923 By P.E. WHELDEN -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

August 1923 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Sports

SportsBASEBALL

August 1923

Article

-

Article

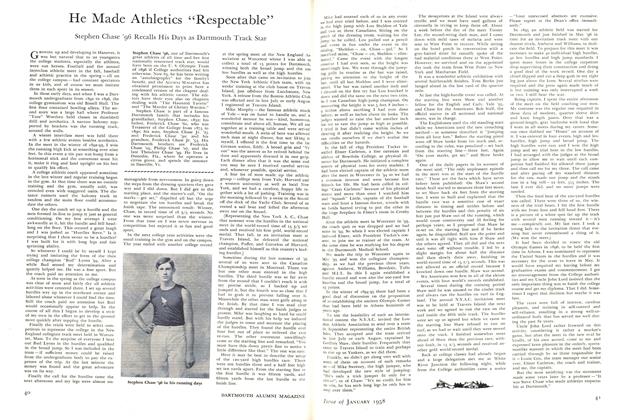

ArticleStephen Chase '96, one of Dartmouth's

January 1958 -

Article

Article2010

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Jennifer Chong -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

May 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleNotebook

Nov/Dec 2004 By GEOFF HANSEN -

Article

ArticleMedical School

DECEMBER 1958 By HARRY W. SAVAGE '26 -

Article

ArticleHottest Shot

MARCH 1972 By RUSTY MARTIN '68