for intensive collections to replenish the alumni fund, it is desirable that the system which Dartmouth employs for supplying money to pay its current bills be recognized as an established factor in the alumni life. Opinions differ as to the best method to be pursued in apportioning and securing quotas—whether or not it should be a matter of class rivalry, whether or not it should be made a general alumni matter; but all the time the solid fact has to be faced that education at Dartmouth costs more than the revenues from a tuition charge that is already about as high as it can be made without closing the doors against worthy men. The difference has to be made up, as it is everywhere else, by a subvention of money; and in Dartmouth's case this usually approximates $80,000 a year.

We have our choice between entering upon a gruelling campaign to secure a permanent endowment, and undergoing a much less strenuous annual campaign to procure the equivalent of interest on an endowment. Thus far it has been found more feasible to resort to the latter expedient. It comes easier for most of us to give, year after year, the small sum which represents a year's interest on $1000 or $5000 than it would to raise the principal sum outright and give it over to the college to invest. Beyond doubt this involves, in the course of years, the giving of more money than an endowment contribution would involve; but it has the merit of being a system which we can work with and which so widely distributes the individual burdens as to produce infinitely less hardship. After mature consideration it is apparently the general agreement that the benefits far outweigh the objections. Therefore, as usual, the spring will bring with it the annual requests for alumni contribution; and the prudent giver will ease his own burdens by the provident gradual accumulation of a sinking fund, little by little, to enable the ready provision of his gift when the time arrives. (By the way, it can be deducted against your income tax.)

That is to say, the prudent giver would do that if he were as wise in practice as he is in theory. What really happens is that almost nobody gives the alumni fund a thought until about the third dun from his class agent. Everybody makes it just as hard as he can, both for the class agent and himself. We all know we've got to do this thing and probably the great majority of the alumni would confess that they were glad enough to do it. But it is so far away, to most of us, that we put off and postpone until, unless vigorously prodded, we utterly forget. It is a reasonable belief that of the 2000 alumni who commonly give nothing at all to this fund a large number omit the gift because of forgetfulness and indifference rather than because of a forthright unwillingness to do anything. The problem of the Alumni Fund Committee is chiefly how to reach the non-contributors—the men who give nothing whatever. Those who always give anyhow are gradually getting educated to the point where the repeated prodding is less needful.

It isn't right and it isn't fair to let this burden fall on two-thirds of our total alumni body, while one-third does nothing at all. One avoids the folly of aspiring to anything like a full 100 per cent, but is it unreasonable to ask that at least 90 per cent of our graduates enroll themselves as contributors in some degree—even if circumstances prevent it from being very much? To content ourselves with two-thirds seems unworthy. There is no reason which an intelligent man can possibly accept for believing that the remaining third cannot give anything whatever, even if it wants to. It can—and we all know it can. Every Dartmouth man in the world could probably contrive to give something, if it were no more than five dollars a year. But a great many men, because they cannot conveniently make it from twenty-five to a hundred dollars, do not give anything. That, we believe, is a harmful attitude, leading to serious injustice to other men and producing a most unwelcome appearance in the comparative tally sheets. It makes it look as if a lot of us didn't care, when as a matter of fact that's true of a very small fraction indeed. What it really means is only that a lot of us aren't terribly interested—and forget.

Well, it's a condition and not a theory that confronts us. Somehow or other that extra money has to be raised every year and we might as well make it a short job, since we know perfectly well we've got to do it. Every class has in it one overworked man who consents to serve as the agent to collect the sum apportioned to his class. It's downright hard work in and of itself, but his classmates usually make it about three times as hard as it needs to be just by plain forgetfulness. That isn't right—and isn't fair, either. Every one of us knows that as well as he knows his way home from the depot. Probably we have all made good resolutions to avoid unnecessary delays and have as promptly forgotten those, also. What about this time, though? The class agents will not begin, probably, until early spring to ask for contributions; but when they do begin why not be ready for them and come down at the first barrel? It saves time and makes it easier for every one concerned—even for yourself. Might it not be a sound scheme to do yourself a favor, as well as the class agent and the college?

It is easy to invent all manner of plausible alibis. You can stress the belief that this plan of raising the equivalent of interest year after year is "illogical" and "economically unsound." You can argue that "students ought to come nearer paying what their education costs them." But in all this you will not convince even yourself—let alone any one else—and all the time that deficit is staring us in the face. It has to be met, if the college is to go on growing and serving. The wiser thing is not to grumble about it but to sign with a Christian cheerfulness on the dotted line. This plea is made well in advance of the time for action, and it will be renewed and repeated. Not all will heed; but if by due diligence we may save some the ink will not be entirely wasted.

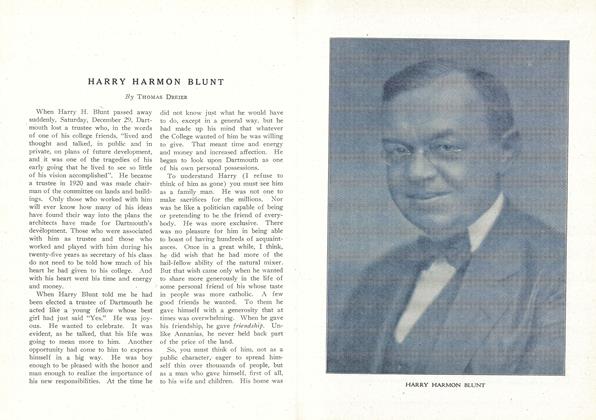

The Board of Trustees and the College generally have suffered a serious loss through the recent and sudden death of Hkrry H. Blunt '97 of Nashua, a member of the board for several years past, secretary of his class, and one of the most active of our alumni body. Mr. Blunt brought to his task as a trustee not only the intelligent interest of a loyal alumnus but an uncommonly sound business judgment and foresight of conditions which made him a most valuable adviser and sage counsellor. A native of New Hampshire and resident in that state, he was unusually well situated to enable an intimate knowledge of the college affairs. Those who had known Mr. Blunt well from the time of his first connection with Dartmouth—he entered as a freshman in the fall of 1893—have learned in those 30 years to appraise at their exceedingly great worth the admirable qualities of mind and heart which he brought to the service of his alma mater, and to see in him a peculiarly strong example of that not too common official, the highly practical trustee. The past year seems to us to have taken an unusually heavy toll of the world's talent, and Dartmouth has suffered, with the rest of humanity, numerous losses which will be difficult to replace. Mr. Blunt's name stands high among the names of men who could ill be spared.

The pendency of the annual Winter Carnival prompts the usual commendatory reference to the Outing Club, which is in our judgment the out-door activity which may be cited as Dartmouth's specialty, par excellence, in that it has facilities both natural and artificial greatly exceeding those of other colleges. Recent investigations have revealed the interesting fact that in the case of many students the prospect of the healthful outdoor sports promoted by the Outing Club has been a great incentive in selecting Dartmouth as the college to attend. At present the membership of this organization includes something like half the undergraduate body, and the winter activities should by no means be supposed to be all that the club offers. In combination with the mountain trails the work of this very admirable organization spreads itself over the entire year, vacations and all.

The benefactions of Rev. Mr. Johnson, so numerous and so constant through recent years, may well prompt other interested alumni who are in position so to do to add from time to time to the club's equipment. Mr. Johnson should certainly not be expected to do it all, although it is doubtful that any subsequent donor will easily equal his record in putting this Dartmouth activity into a position from which it may exert a beneficent influence on our college life.

No one is ever able to predict what a season may bring forth. The present winter, getting away to a mild start, may provide the requisite snow and cold to enable the usual Carnival festivity. In any case the emphasis which this cherished event lays on one of Hanover's traditional charms comes not amiss.

A chaste and holy joy apparently pervaded the editorial bosoms of both the Nation and the New Republic on discovering that the collegiate authorities at Hanover entertained no idea of preventing by force and arms the oratory of so radical a reformer as William Z. Foster. At all events both publications made Mr. Foster's visit the occasion for ejaculations of thankfulness that at least one American college had not attempted to clamp down the lid on free speech. The fact that the auditors, who had persuaded themselves that they had a curiosity to hear Mr. Foster, gave him a respectful hearing instead of turning the meeting into a riot seems further to have impressed the New Republic and the Nation. Incredible! Astounding! And, shall we add, perhaps a little disconcerting?

In such cases a college isn't supposed to act in this way. It is supposed to be shocked and scared. It is hardly playing the game to let the radical exponent expound with such obvious indifference. As a general thing, there is afforded something for the critics to be wildly indignant about. This being denied in the Hanover case, the next best thing is to commend the open-mindedness of the College as something utterly unprecedented—and then rely upon scandalized alumni to provide the usual excitement by rushing into print with denunciations of radicalism in general. This we gather from the New Republic's hopeful remark that already President Hopkins has had letters of indignant protest.

Now if the alumni are as wise as the president of the College is, they will refrain from giving this belated satisfaction to the professional malcontents, either in college or outside. The editors of this MAGAZINE have as little use as any one on earth can have for the doctrines of William Z. Foster and his kind; but they realize how silly it is to magliify the importance of such an exhibition and thus provide the expected fun for the extremists, who want nothing better than a chance to play the martyr. Whether or not it was so in this instance we do not pretend to know, but as a very common thing such invitations to a spectacular firebrand are intended as provocations. If only the sober-sided conservatives can be prodded into a fury by the prospect of a speech by some apostle of the ultra-radical faith, all that is really desired has been done. The actual preachment then loses its significance and the episode serves its turn in promoting a frenetic chatter about the sacredness of free speech and the enormity of suppressing it. In 99 cases to the hundred, one suspects the essence to be a bit of hectoring designed to discover just how far one must go in order to start something. In which event a cordial invitation to go as far as one likes must be rather maddening.

As a result the College has had some rather equivocal advertising in the Nation and New Republic as a place where students are quite free to hear both sides of every question, regardless of its manifest futility. Those ardent souls who believe it to be a duty to listen when some protagonist asserts that possibly the sea is boiling hot, or that probably pigs have wings, or that maybe two and two make half-a-dozen, are always delighted to discover minds so wide-open that they do not dismiss such hypotheses with contempt. But in the depths of the radical soul one suspects there is a distinct disappointment none the less, when the expected opposition does not develop and when, instead of attempting repression, the doors are opened wide.

William Z. Foster has not been the only orator of note whose appearance was likely to produce adverse criticism in alumni circles. No less a personage than the erudite William Jennings Bryan has also been listened to. His object all sublime was to convert the students and faculty to his view that it is impious to offer instruction' which recognizes the evolutionary theory. Regarding the ancient writings in Genesis as the inspired word of God, Mr. Bryan affects to see in scientific research a questioning thereof which is on its face a sort of blasphemy. From the comments of the college press it appears that, while Mr. Bryan received no less respectful attention than did Mr. Foster, he left behind no great number of converts to his theories. The Daily Dartmouth's brief but pithy comment that the auditors "did not check their intelligence at the door" may suffice to show what was the breadth and depth of the impression produced by the devout Fundamentalist on the student body. The faculty, it may be safely assumed, presented a hopeless case from the start.

It will be interesting to see what next can be thought of as a test for tolerance. There is extant in the country a very considerable body of rapscallion doctrine with fevered exponents all quite ready and willing to talk—especially if it is likely to shock middle-class respectability into open denunciation. One is daily adjured by these high-strung enthusiasts that it is the part of wisdom to listen to every one with a new wheeze, political, economic, or social, on the off-chance that amid the chaff may exist a single kernel of real wheat. How can we be sure that gold will never be expressed from sea water? Is it absolutely certain that there will never be sunshine extracted from cucumbers? Communities may yet be able to exist by taking in each other's washing, and some fine day a venturesome philosopher may actually lift himself by his own bootstraps and go sailing right over the chapel tower— to refute the stodgy reactionaries who said he couldn't do it and that it was nonsense to make the attempt! That it is a waste of time to listen to both sides of some propositions is stalwartly denied.

Anyhow it is something to have commanded the unstinted praise of the editors of the Nation and the New Republic.

With the College at its present size and with the fraternities at their current strength it appears from statistics that only a little more than half the student body can well be enrolled in fraternity lists. Last year, if the tabulation before us is accurate, there were 56 per cert of the College enrolled in the several fraternities and 44 per cent not so enrolled. Of those who received degrees at Commencement, 65 per cent were fraternity men.

In many ways this situation is unfortunate, or seems so to those of us whose recollection goes back to the time when pretty nearly every man in college could be a member of some fraternity if he chose. In those days there were berths enough for all. Today there is nothing like room enough, although the number of fraternities is tremendously enlarged over what it was in the '9os. Apparently there are practical obstacles in the way of steadily increasing the quota of competing fraternity chapters, and equally practical ones in the path of greatly increasing the size of annual delegations.

In the alumni bulletin of December 13 the opinion was expressed that "it would be better to have either 10 per cent or 90 per cent enlisted in fraternities than our present 56 or 60 per cent." As to that, judgments may differ—more especially as to the lower figure. But it does seem undesirable to make the division so nearly even as it must be with conditions as they are, and hence most will subscribe readily to the statement that at least it would be better if 90 per cent were members of Greek Letter societies than to have only 60 per cent. The remedy, as we see it, is not one that can be greatly accelerated. Such situations have to bring their own cure with them by a process of natural growth —stimulated to some limited extent by efforts of the Interfraternity Council.

It appears to be fortunately true that no alarming trend toward avowed cliques, or a domination of undergraduate politics on a basis of fraternity vs. non-fraternity organization, is as yet revealed. The possibility of it is naturally apparent, however, and its menace of the cherished democracy of Dartmouth is clear enough, human propensities to jealousy and envy being what they are. One hopes that the disparity between available fraternity "bids" and the total of our undergraduate population will gradually diminish—and that in the interval the temptation to make college affairs turn on the rivalries of those who are in the societies and those who used to be known classically as "oudens" will be resolutely avoided.

We believe that the glib assertion so often made, to the effect that non-fraternity men constitute the majority of those who receive honors at Commencement, is incapable of substantiation and is really based on a desire to discover compensations. The facts appear to be that the percentage of honor men who are also fraternity men averages about the same as does the proportion of fraternity men to non-fraternity men. In 1923, 54 per cent of the seniors enrolled in the three honor groups were members of societies; and in 1922 the percentage ran as high as 64. It is doubtful that society affiliations have very much to do with the case. But the part which fraternity life plays in a college career is so great and so pleasant that it is clearly proper to make it as nearly universal in its availability as is possible.

Belated comment on next year's football schedule is no doubt a work of supererogation. It is widely regarded as coming as near the ideal schedule as it is presently possible to come. It does impose a serious burden by concentrating a number of hard games with major colleges in mid-season, but that is absolutely inevitable if Dartmouth is to play Harvard, Yale and Cornell, along with others only less formidable, in a single autumn. It should be added, perhaps, that in renewing ancient relations with Yale the list for next year is especially notable and will be universally agreeable. We incline to deprecate vainglorious references to such combinations as "Big Three" or "Big Four" as affected by such schedules. That sort of thing may best be left to the sporting writers of metropolitan and other newspapers, rather than promoted by collegiate or alumni boosting.

As an incidental point, while we are speaking of sports, there has sprung up within the year a decided and on the whole salutary reaction against overdoing the business of professional coaching "from the bench", especially during the progress of baseball games, as inconsistent with the better theories of college athletics. The same evil is more or less marked in the case of football, but in that realm it appears to be very difficult to eradicate. The worse phases of it are manifested in baseball, where the hired professional, commonly a retired bigleague performer, issues his directions to the pitcher and batsmen as is done in professional games, thus substituting the judgment of a wholly outside director for the judgment of the team and its captain. This often degenerates an intercollege game to the estate of a contest of rival coaches, who are matching wits in the moving of their pawns on the field. It has long been regretted by observers and the revolt against it seems to us a proper one.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

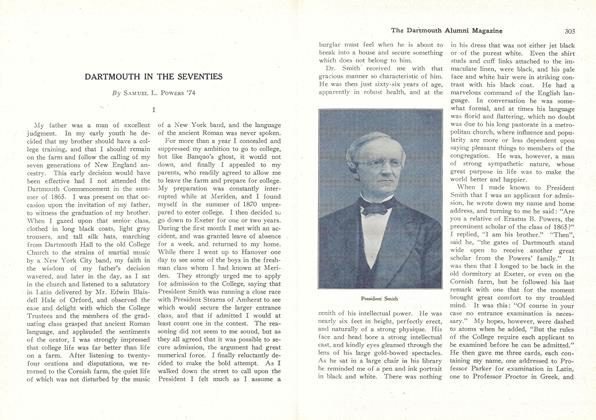

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN THE SEVENTIES

February 1924 By Samuel L. Powers '74 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH JOTTINGS OF A SOMEWHAT DESULTORY READER

February 1924 By Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Class Notes

Class Notes$1000 REWARD PEARL NECKLACE

February 1924 -

Article

ArticleHARRY HARMON BLUNT

February 1924 By Thomas Dreier -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

February 1924 By H. Clifford Bean