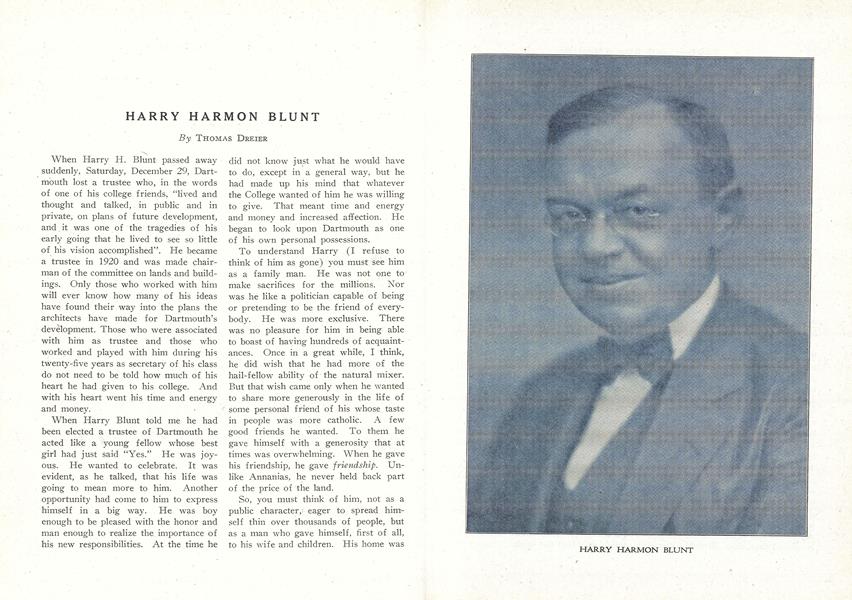

When Harry H. Blunt passed away suddenly, Saturday, December 29, Dartmouth lost a trustee who, in the words of one of his college friends, "lived and thought and talked, in public and in private, on plans of future development, and it was one of the tragedies of his early going that he lived to see so little of his vision accomplished". He became a trustee in 1920 and was made chairman of the committee on lands and buildings. Only those who worked with him will ever know how many of his ideas have found their way into the plans the architects have made for Dartmouth's development. Those who were associated with him as trustee and those who worked and played with him during his twenty-five years as secretary of his class do not need to be told how much of his heart he had given to his college. And with his heart went his time and energy and money.

When Harry Blunt told me he had been elected a trustee of Dartmouth he acted like a young fellow whose best girl had just said "Yes." He was joyous. He wanted to celebrate. It was evident, as he talked, that his life was going to mean more to him. Another opportunity had come to him to express himself in a big way. He was boy enough to be pleased with the honor and man enough to realize the importance of his new responsibilities. At the time he

did not know just what he would have to do, except in a general way, but he had made up his mind that whatever the College wanted of him he was willing to give. That meant time and energy and money and increased affection. He began to look upon Dartmouth as one of his own personal possessions.

To understand Harry (I refuse to think of him as gone) you must see him as a family man. He was not one to make sacrifices for the millions. Nor was he like a politician capable of being or pretending to be the friend of everybody. He was more exclusive. There was no pleasure for him in being able to boast of having hundreds of acquaintances. Once in a great while, I think, lie did wish that he had more of the hail-fellow ability of the natural mixer. But that wish came only when he wanted to share more generously in the life of some personal friend of his whose taste in people was more catholic. A few good friends he wanted. To them he gave himself with a generosity that at times was overwhelming. When he gave his friendship, he gave friendship. Unlike Annanias, he never held back part of the price of the land.

So, you must think of him, not as a public character, eager to spread himself thin over thousands of people, but as a man who gave himself, first of all, to his wife and children. His home was my second home for a dozen years. I visited it the first day I met him, and Mrs. Dreier and I shared the joys of his last Christmas day with him and his family. His home was known to me under all sorts of conditions for all those years and it was the one home about which I thought "and talked when I wanted to tell people about a place where love was king. He made his home folks happy. There was more joy in the place when he returned, even if he had only been absent for half a day at his mill in Nashua. Of his home it could always be said, "There was much love in the place."

His business was linked closely with his home. The Wonalancet Company was his own creation. He had dreamed it into existence—had made it what it was, the leader in its field. He was a keen, shrewd, clear-thinking bargainer. He liked to bargain. There was much of the Yankee trader in him. But he had qualities which a David Harum would think unnecessary. He had sense enough to know that his customers had to be made loyal to him—that no business could be built on a basis of bargaining which resulted in loss to either customer or seller. His family life had been successful because he had served, so he kept alive in all his business dealings the principles that had worked so magically in his home.

He was not the kind of business man who could play the part of an absentee owner. It would never satisfy him to sit in a central office and keep in touch with many businesses by means of reports. He had to be closer to the people he served than that. Possibly that was one of his limitations. In that sense he

was not a great organization man. He was too much of an individualist. He wanted things done his way—and usually he knew exactly what he wanted. It is true that his failure to consult others more expert than he in certain things caused him to make mistakes. In developing his home grounds in Nashua he moved stonewalls and big trees over and over again until his friends asked him why he did not put them on casters to save expense. But that was his way of having fun. It was a clean, wholesome way of having fun. He was willing to pay for his mistakes—and he did not want anyone to control his actions so that he would be denied the privilege of experimenting. The success of his business is evidence enough to prove that his successes far outblanced his failures in that field.

One time he had an opportunity to take over a big business which might have been merged with his own. He refused because it would call for an organization so big that he could not give to all its departments his intimate, personal attention. His attitude, you see, was professional. He was the artist. He preferred ten acres, every inch of which would be beautified to a thousand acres, most of which would be cared for superficially. A comparatively small business run perfectly, handled by a small, select staff of happy people, was finer in his eyes than a huge enterprise whose only great merit was that it made lots of money. To understand this fully you would have to know both his home and his office, both filled with beautiful furniture, pictures, books, flowers—the things that feed the spirit.

What fun he had "anteeking"! In Europe, Peru, or in our own country he spent hours wandering through antique shops. He knew furniture. Walking by an old house in New Orleans he saw an old sideboard painted red used for a chicken-coop. He bought it in a hurry because he had little time that day. Underneath the paint was old mahogany. He bought the old thing because the lines were right and he knew that an artist had fashioned it out of honest wood. He was always looking for mahogany quality under coats of cheap red paint. Nothing delighted him more than to find that a man was better than people suspected.

The Dartmouth trusteeship was a greater gift to him than those responsible for his election realized. He had just about reached the end of his labors in making his own home place beautiful. So many ideas had crowded into his mind because of his studies of architecture, landscape gardening and interior decorating, that he needed a greater outlet. He was not only ready but eager to give. It seemed that he had been preparing himself unconsciously for doing just that work which the College needed to have done. Those friends of his who worked for his election had their faith in him justified. As President Hopkins said in a letter:

"In his devotion to college needs, his indefatigable zeal within the range of his own interest, and his broad-minded acceptance of policies into favor of .which he did not come instinctively, he has been tremendously helpful to the College, and has rendered service that probably no other man in our group could have done."

;If he could have his way, Dartmouth would have the most beautiful plant in the country. He believed that boys, no matter how much like young animals they may act at times, are influenced by beauty. The old, bare, uncomfortable college rooms may have served well enough in pioneer days, but he wanted the boys of today to have rooms which would raise their standards—make them want the finest, most beautiful things in their own homes and offices. When he took guests to Hanover he invariably led them down into the clean, modern kitchen in College Hall with whose remodelling he had so much to do. No one can know how much of his time was spent planning with those interested in the Dartmouth of fifty years hence.

I said he was not a lover of men in the mass, yet I will not make the mistake of saying that he was not a lover of Dartmouth men in the mass—especially those youngsters coming along with whose college environment his work as trustee had so much to do. He had no son of his own, so Dartmouth boys became his sons in his planning for them. What a pity all of them did not know him as his friends knew him—the joking lover of foolery, surprisingly childlike in so many ways. To see him looking important one would never suspect him of spending much of his time cutting out funny pictures, pasting them on letter sheets and writing insulting notes under them to friends at a distance. And what a reader he was! His home is filled with books.

But this is not to be a book about him. In writing about him my trouble is that I was too close to him. For years he and I lunched together nearly every

Monday. What things we have talked about! He was no superman. Don't think that I think so. But he was lovable, generous, clean, helpful, and trustworthyall the way through. He had his peculiarities, too. He wanted his own way, and if opposed he would have it. But if one understood him and worked in harmony with that understanding he would make any sacrifice of his comfort or possessions for one. Notwithstanding all the affection he received, he was hungry for more. His great prayer was, "Make me lovable, O Lord." And that prayer certainly was answered.

Of course, you understand, I write this as a friend who knew him about as well as one man can know another—and who loved him. His little prejudices, his desire to have his own way, his—but why waste time talking about those qualities which only made him so delightfully human? He was the sort of Dartmouth man who made those of us who are not Dartmouth men wish to goodness we might boast as he boasted of the Dartmouth of today and could dream as he dreamed of the Dartmouth of tomorrow. He was a good he-man.

HARRY HARMON BLUNT

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWhatever be the time selected

February 1924 -

Article

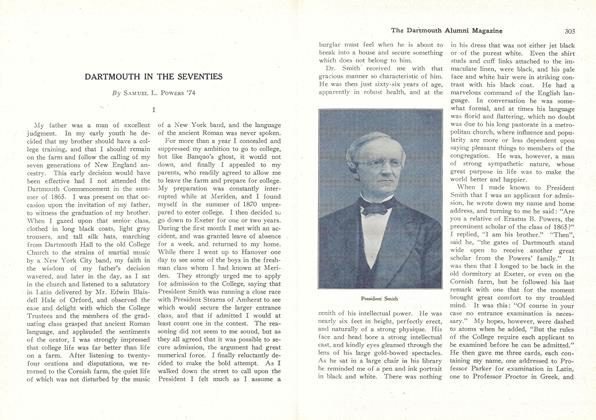

ArticleDARTMOUTH IN THE SEVENTIES

February 1924 By Samuel L. Powers '74 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH JOTTINGS OF A SOMEWHAT DESULTORY READER

February 1924 By Fred Lewis Pattee '88 -

Class Notes

Class Notes$1000 REWARD PEARL NECKLACE

February 1924 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

February 1924 By H. Clifford Bean