What do we think of a college president's saying that if Trotzky were available that president would have him address the boys in his college?

Well, we think several thing's. One of them is that this college head is sure of his faculty and of the vitality of its teaching. We should say that he is not afraid to pit the year-round leadership, instruction, and influence of his teaching staff against the lecture of any one man.

We should think also that probably this college president is confident of the shaping, controlling influence of collegiate tradition; that he believes a college that has lived through the Revolution, the critical period preceding the adoption of the Constitution, the decades of tense struggle out of which came constitutional unity through epoch-making interpretations of law one of which was provided by the college itself, the long slavery debate, the Civil War, and the industrial revolution, and steadily held to certain cultural ideals all the time—that such a college and its traditions need not be fearful that an hour's preaching of economic theory altogether out of joint with that of its country should undo the work of a century and a half in the minds of the boys.

We think that this president who would let Trotzky talk himself out to the undergraduates under his charge believes in these young men believes in them so fully that he depnds upon them to grow strong and become settled in sound opinion in the very clash and struggle of opinion.

Of course, what Dr. Hopkins said in Chicago is horrifying to some. To think of subjecting the boys to the danger that Trotzky might convert them to Bolshevism, or at least weaken their faith in the existing social order! But the simple fact is that the boys at Hanover have been hearing all sorts of visiting speakers for years and—well, we all know the kind of man who is being graduated up there. You haven't heard of any of them being leaders in radicalism and preachers of revolt, have you? It simply does not work that way. To be sure, there is a very ancient and therefore dearly loved belief that the way to train minds is to strap them, so to speak, to a board and place them in an air tight enclosure, so that they cannot, by some chance, even be blown sideways on the board. They come out flat and straight enough. Sooner or later, however, these, as well as less rigidly clamped down intellects, have to come in contact with ideas not in harmony with those prevalent in our country. Which is preferable, that the young man be fussed up by these notions and finally, perhaps, fall back on what he has been taught, or that he be able to say, "Oh yes, I heard that in college, heard it explained by So and So, who believes it and knows more about it than anybody else, and made up my mind while hearing him that it doesn't work and cannot be made to work amongst our people?" In the first instance you have an instructed intellectual automaton; in the second, an educated man of opinion.

By the way, wouldn't you like to hear Trotzky yourself. We should, for a variety of reasons. Unless this striking figure is a dozen men at least in one, and so has a dozen opinions on the same subject and says as many things, he has been a good deal misquoted. We should really like to hear the man himself and get from him what he really does think. But that is another story. As for letting our boys hear him, that would be just about the surest measure we could take to protect them in later life against some of his known notions.

Another favorable editorial was the following from the Rochester (N. Y.) Democratand Chronicle :

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE POW WOW

April 1924 By E. Russell Palmer '10 -

Article

ArticleIS THE COLLEGE EDUCATIONAL PROCESS ADEQUATE FOR OUR MODERN WORLD?

April 1924 By Charles Dubots '91 -

Article

ArticleThe Chicago Pow Wow which

April 1924 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1916

April 1924 By H. Clifford Bean -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

April 1924 By Perley E. Whelden, John P. Wentworth

Article

-

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE TUCKER ALUMNI FUND

March, 1914 -

Article

ArticleDR. E. E. JUST '07 RECEIVES MEDAL

March, 1915 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

November 1983 -

Article

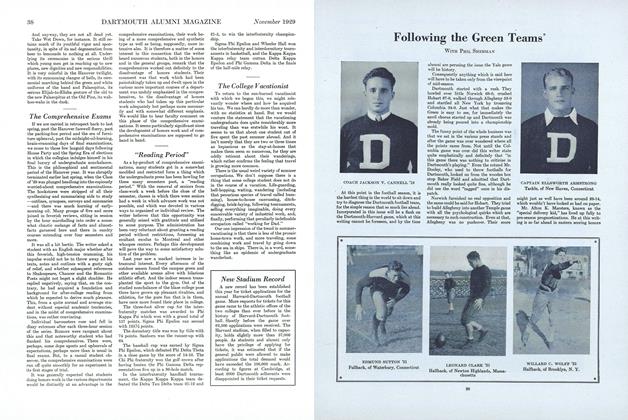

Article"Reading Period"

NOVEMBER 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

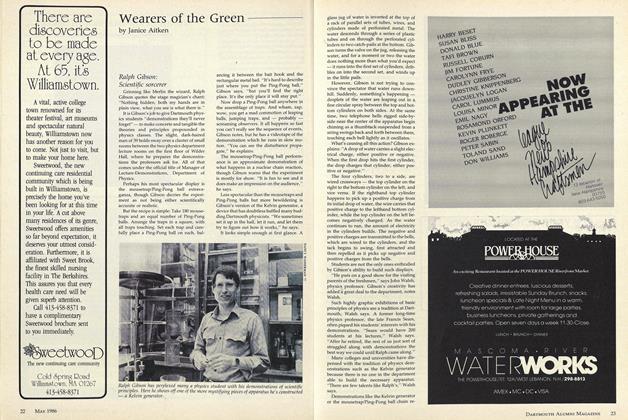

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

MAY 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

ArticleNotebook

Sept/Oct 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN