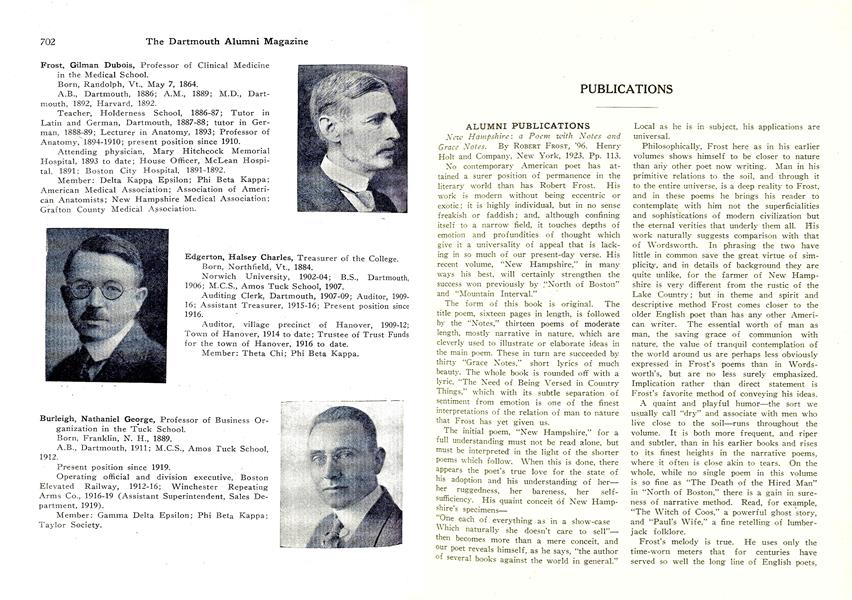

New Hampshire: a Poem with Notes andGrace Notes. By ROBERT FROST, '96. Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1923. Pp. 113.

No contemporary American poet has attained a surer position of permanence in the literary world than has Robert Frost. His work is modern without being eccentric or exotic; it is highly individual, but in no sense freakish or faddish; and, although confining itself to a narrow field, it touches depths of emotion and profundities of thought which give it a universality of appeal that is lacking in so much of our present-day verse. His recent volume, "New Hampshire," in many ways his best, will certainly strengthen the success won previously by "North of Boston" and "Mountain Interval."

The form of this book is original. The title poem, sixteen pages in length, is followed by the "Notes," thirteen poems of moderate length, mostly narrative in nature, which are cleverly used to illustrate or elaborate ideas in the main poem. These in turn are succeeded by thirty "Grace Notes," short lyrics of much beauty. The whole book is rounded off with a lyric, "The Need of Being Versed in Country Things," which with its subtle separation of sentiment from emotion is one of the finest interpretations of the relation of man to nature that Frost has yet given us.

The initial poem, "New Hampshire," for a full understanding must not be read alone, but must be interpreted' in the light of the shorter poems which follow. When this is done, there appears the poet's true love for the state of his adoption and his understanding of herher ruggedness, her bareness, her selfsufficiency. His quaint conceit of New Hampshire's specimens—

One each of everything as in a show-case hich naturally she doesn't care to sell"— then becomes more than a mere conceit, and our poet reveals himself, as he says, "the author °f several books against the world in general." Local as he is in subject, his applications are universal.

Philosophically, Frost here as in his earlier volumes shows himself to be closer to nature than ariy other poet now writing. Man in his primitive relations to the soil, and through it to the entire universe, is a deep reality to Frost, and in these poems he brings his reader to contemplate with him not the superficialities and sophistications of modern civilization but the eternal verities that underlv them all. His work naturally suggests comparison with that of Wordsworth. In phrasing the two have little in common save the great virtue of simplicity, and in details of background they are quite unlike, for the farmer of New Hampshire is very different from the rustic of the Lake Country; but in theme and spirit and descriptive method Frost comes closer to the older English poet than has any other American writer. The essential worth of man as man, the saving grace of communion with nature, the value of tranquil contemplation of the world around us are perhaps less obviously expressed in Frost's poems than in Wordsworth's, but are no less surely emphasized. Implication rather than direct statement is Frost's favorite method of conveying his ideas.

A quaint and playful humor—the sort we us.ually call "dry" and associate with men who live close to the soil—runs throughout the volume. It is both more frequent, and riper and subtler, than in his earlier books and rises to its finest heights in the narrative poems, where it often is close akin to tears. On the whole, while no single poem in this volume is so fine as "The Death of the Hired Man" in "North of Boston," there is a gain in sureness of narrative method. Read, for example, "The Witch of Coos," a powerful ghost story, and "Paul's Wife," a fine retelling of lumberjack folklore.

Frost's melody is true. He uses only the time-worn meters that for centuries have served so well the long line of English poets, but by the power of his genius he has made them fresh and individual for his immediate purposes. His skill in this respect would be an ample refutation, if one were needed, of those contemporary writers who with less to say and less need of saying it cry out that poets can express themselves today only by inventing new and fantastic forms. Every- where his singing quality is evident; had I space, I might quote lengthily to show the beauty of his rhythms, but I must forbear and leave to my readers the pleasure 'of discovering it for themselves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT ARE THE TRUSTEES DOING?

June 1924 By Lewis Parkhurst '78 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleSaturday Morning Session

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleThe Responsibility of the College to its Alumni

June 1924 By P. S. M. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

June 1924 By Perley E. Whelden

F. L. Childs

-

Books

BooksMichelangelo: the Newdigate Prize Poem

August 1924 By F. L. Childs -

Books

Books"The Great Adventure"

June, 1926 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksWEST-RUNNING BROOK

June 1929 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksA BRAVERY OF EARTH

AUGUST 1930 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksPEN-DRIFT: AMENITIES OF COLUMN CONDUCTING

APRIL 1932 By F. L. Childs

Books

-

Books

BooksCRUCIBLE

May 1937 By E. P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksMONEY AND CREDIT

May 1935 By G. W. Woodworth -

Books

BooksLABOR'S SEARCH FOR MORE

May 1937 By Hugh L. Elbree -

Books

BooksA SWINGER OF BIRCHES:

June 1957 By JAMES M. COX -

Books

BooksOLD QUOTES AT HOME.

JANUARY 1968 By MAUDE FRENCH -

Books

BooksCliff-Hanger

June 1980 By Peter D. Smith