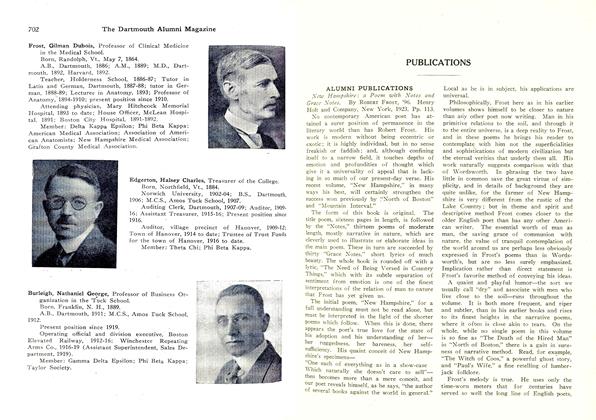

By Robert Frost '96. Henry Holt and Co.

The position of Robert Frost in contemporary American poetry is so securely high that the publication of a new volume can do little to enhance it, and yet the readers of "West-Running Brook" will feel that something of breadth has been added to his reputation by these lyric pages. Frost is peculiarly our poet of northern New England life; he understands and interprets as no one before him has done certain of the quieter and deeper phases of nature and humanity as they reveal themselves in New Hampshire and Vermont. This little book deals with similar themes and stirs similar emotions to those of his earlier volumes, but there is in it a calm maturity of thought and feeling that shows development and proves him to be no mere repeater of past performances.

The tone of the volume is more personal, less objective than that of "North of Boston," and "Mountain Interval"—even than that of "New Hampshire." The emphasis on narrative incident that marked the earlier works has faded, while the stress, always present, on pure emotion has been intensified. No one who has loved Frost's other poems will fail to enjoy these, and many new admirers, to whom the earlier writings seemed too austere, will doubtless be attracted by the mellow gentleness of the present lyrics.

Man's kinship with nature in one or another of her various but usually unnoticed phases furnishes the central idea for each of the brief, clear-cut poems in "West-Running Brook." Melting snow in springtime, dripping rain at night, a curving shore-line, smoke from a lonely farmhouse chimney, a treegrown and flower-starred meadow, a roaming she-bear, fireflies, sand dunes, an eddy in a contrary brook—such are the slender objects that stir the poet's feeling; his sympathetic insight turns their slightness to strength, his inspired gift of song shapes their meanings in unforgettable words, permeated with his native humor and his native philosophy. I know of no one among our modern poets who preserves so fine a balance between man's littleness and man's greatness, between inexorable nature and kindly nature. For instance, place

"An hour of winter day might seem too short To make it worth life's while to wake and sport"

beside

"She may know cove and cape, But she does not know mankind If by any change of shape, She hopes to cut off mind."

The form of these new poems invites no comment other than that which has so often been given Frost's earlier work. Here again is utter simplicity of phrase, with its accompanying quiet beauty; effective use of repeated words and echoed sounds; slow, even cadence wedded perfectly to thought; entire naturalness of expression and of music. The volume is a small one, but precious.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Faces in the Windows

June 1929 By Clifford Hayes Smith '79 -

Article

ArticleAviation Opportunities for Dartmouth Men

June 1929 By Lieut.Barrett Studley,U.S.Navy -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1923

June 1929 By Truman T.Metzel -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1929 -

Article

ArticleA Visit to Hanover

June 1929 By E.W.Field -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1898

June 1929 By H.Philip Patey

F. L. Childs

-

Books

BooksNew Hampshire

June 1924 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksMichelangelo: the Newdigate Prize Poem

August 1924 By F. L. Childs -

Books

Books"The Great Adventure"

June, 1926 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksA BRAVERY OF EARTH

AUGUST 1930 By F. L. Childs -

Books

BooksPEN-DRIFT: AMENITIES OF COLUMN CONDUCTING

APRIL 1932 By F. L. Childs

Books

-

Books

BooksSpinning Spheres a Story of Copernicus

April1935 -

Books

BooksCOLLEGE PHYSICS

July 1960 By ALLEN L. KING -

Books

BooksGUIDANCE IN CATHOLIC COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES. Edited

October 1949 By Howard F. Dunham '11 -

Books

BooksVASSI AND FIDELES IN THE CAROLING

August 1945 By John R. Williams '19 -

Books

BooksSIXTY DARTMOUTH POEMS.

MARCH 1970 By ROBERT H. SIEGEL -

Books

BooksPROCEEDINGS OF THE SECOND N. H. BANK MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE

October 1941 By William A. Carter '20.