writing in a recent number of the World's Work on the general topic of college sport, raises the incidental question of its "cleanness" from the taints of professionalism and of a general over-emphasis. His theory is that to maintain itself at the required pitch of efficiency to appropriate ends a sport must satisfy certain definite requirements. "The greatest value of any game, professional or amateur," he says, "is not in its spectacle at great contests, but in the amount of influence it exerts among people of all ages, and particularly among the younger generation, toward clean living, and moderate, sensible exercise, which in the end means good health and long life. No sport that is not clean can be a powerful influence, and no sport that is not spectacular in some of its aspects can have any great influence."

This is a topic that will not down. It is apparent from various recently published comments that college authorities everywhere incline to resent the tendency of the public, and especially of certain alumni, to lay a much greater stress on intercollegiate athletics than is strictly merited. A few critics insist that the tendency of college sports is toward professionalization. More object that the athletic budget in larger institutions rivals that of the college itself, that the coaches are paid more than the professors, and that here and there a disposition is manifested by alumni groups to seek out promising athletes to send to college, rather than to recruit the student ranks by inducing embryo scholars to matriculate. On the whole, however, -this is a natural outcome of the treatment of sports by the public and especially by the press. It is a side of academic life which is usually described by modern sportwriters as "colorful." There is nothing colorful about classroom activities; but the games—especially football games, which are but meagrely represented in professional fields—-lend themselves to the needs of the sport page of the average newspaper after baseball's tumult and shouting have died. One need not greatly blame the average alumnus for coveting a proud position in the eyes of the chroniclers, although one may justly demand that the zeal for promoting this celebrity be confined within defensible channels.

That the value of intercollegiate sport inheres very markedly in "the spectacle of great contests" will be stoutly insisted by many, with all due respect to Mr. Camp, whose personal interests as an exponent of physical culture would incline him to exalt that phase of the question. Out of the millions of people who take an interest in college athletics, comparatively few would honestly say they esteemed football and other sports mainly because of their incentive toward "moderate, sensible, out-door exercise conducing to health and prolonged life." It may well be-that such should afford the compelling reasons—but the fact is they do not, and it is idle to pretend that they do. The virtue inheres quite as surely in the spectacular, with its incidental effect on "advertising the college" and its undoubted promotion of a generous and healthful rivalry among institutions of learning which is reflected in the vague thing we may call the '"morale" of the student body. Let us be frank to admit the raisons d'etre. If all that ever came out of college sports were physical exercise for the entire student body, college athletics would be more or less boresome to the great bulk of the communityabout as enlivening as the Daily Dozen and about as interesting to the general world as the average bedtime story.

The spectacular features will have to be accepted as affording a large part, and to most people the major part, of the excuse for being enjoyed by intercollegiate sport. That being so, it is in order to make the best of it by not making too much of it. Mr. Camp is well within the bounds of truth when he decries professionalized sports as lacking the proper degree of influence. It is when the desire to produce a winning team overmasters the proper sense of proportion that we believe the time' arrives for criticism. That is the thing it is always necessary for every alumni organization to beware of and to guard against. One may admit the great desirability of a winning team without implying that every means for procuring a winning team can be justified. As a matter of fact there is never the slightest satisfaction in the performance of a team which its own supporters inwardly feel to be the reverse of bona fide. Any college with money enough among its sporting backers could hire a company of expert players to pose as students. The real glow comes when you can show a first-grade team made up of men whom you know to be in college primarily to learn something out of books of men who are incidentally athletes, rather than incidentally students.

It is our present belief, and for this we are devoutly glad, that most of the colleges are, alive to this phase of the athletic question and are honestly insistent on the purification of the athletic temple. The reasons are adequate. For one thing, any one can see the little worth of reducing a college athletic establishment to the professional basis. It gives only a specious and transitory glory. It speedily invites the distrust of observers and impairs reputation in a dozen different ways. Worse yet, there's a tastelessness about the victories that have to be won in that way.

Nevertheless there remains an insidious and very indirect form of professionalism which has to be constantly dreaded, whereby, in spite of all one can do or say, perfectly well-meaning alumni groups sometimes seek to recruit the college elevens, or the college nines, or the college track teams, with boys whose one great claim to regard is what they can do on the track, diamond or gridiron. This is sometimes glossed over by a process of self-persuasion, until the sponsors for the recruit convince themselves that it isn't really the athletic side of their candidate that weighs most with them. "He's a good lad," they argue. "Why regard the fact that he shone at quarterback in his prep school as a handicap?" The difficulty is to draw the line between regarding it as a handicap, and regarding it as the one real reason for taking an interest.

It is pleasant to feel, as the MAGAZINE honestly does feel, that Dartmouth suffers vastly less from this indirect form of professionalism than was the case in by-gone years. There seems to be springing up a very genuine feeling of alumni pride in the fact that college teams are not only beyond the need of special pleading to establish their bona fides, but are also notable for the lack of any worry over eligibility on the part of the players. The very best evidence of athletic' purity is a team in which no prominent member is a source of anxiety to the Dean. The players who are practically induced to go. to college merely to adorn the athletic scroll commonly do not figure in the top half of the class; and when you get a winning eleven that is pretty nearly of Phi Beta Kappa grade throughout, you may be sure that what you have is the real thing.

An interesting development of student participation in college affairs has been revealed by the report of an undergraduate committee at Harvard, pronouncing against the "honor system" in examinations, at least as applied to Harvard. The report intimated that while the honor system might -be advantageous to employ in a smaller college, it seemed to the committee inapplicable with good effect to a larger one. The inference is that the old system of proctoring still has favor at Cambridge.

There is no very clear reason why the honor system should be more desired in smaller colleges than larger ones, save the possibility that students are more intimately acquainted in the former. The theory of the honor system is that men. placed on their word not to cheat in examinations will keep to that word when not overseen by a system of faculty espionage, where, if there were no such pledge, but if a very obvious and suspicious overseer were present, it might be regarded as fair game to circumvent the latter. The testimony of the colleges varies as to the efficacy of honor systems, but it seems not to have impressed the Harvard committee with reasons for favoring it.

The honest student who has no intention of cribbing in any circumstances can have no very strong objections to the presence of a proctor, since the latter's presence or-, absence makes no conceivable difference in his conduct. The sole question is the effect on the student potenially open to temptation. Is the student in a small college less open to temptation than in a big college? Is that why the honor system is imagined to function better in the little college? We feel some doubt of this. There is also a vague doubt that placing men on their honor and leaving them alone, relying solely on their sense of obligation to a plighted troth, is as efficacious as theorists assume. It should, however, be quite as efficacious at Harvard as elsewhere. Beyond doubt there is a sense of honor, widely distributed, which will make young men slow to break their pledges when thus given; but we must be mindful of the fact that a breach, if made, would pass undetected unless information of it were given—also a thing from which students would be likely to revolt.

Wherefore, although doubting somewhat the various reasons given, it is this MAGAZINE'S opinion that the Harvard committee on the whole reached a sensible and practical conclusion. The one obstacle is the fact that young men in that situation sometimes feel that the

presence of an overseer is a tacit inspiration to evade his vigilance if possible, where absolute dependence on good faith would be an inspiration to be honest. So much in this is theoretical that we incline not to place much stress upon it and to admit that from the practical point of view the proctor system is hard to beat and impossible reasonably to decry. The proctor's presence does to a certain extent imply that the faculty prefer to watch while the young men fill their bluebooks, and may be slightly unflattering in consequence. But the student committee at Cambridge appears to feel that this vigilance is not without its grounds of reason and we see no occasion to file any dissent.

It all comes back to the validity of the proposition that men put on their honor won't cheat, where men not put on their honor very likely will—especially if they are being watched. Much has to be taken for granted under the honor system. The other, no one has any doubts about. Do men crib when unwatched and told that honesty is purely up to them? Who really knows? The impulse is usually against doing it—but temptations are strong, and no one is likely to turn informer in case one yields. "It isn't done," as they say in England. So one assumes that honor systems work, when possibly this involves a strain on the credulity.

The recent meeting of the Secretaries Association has again demonstrated the important place which this body occupies in the organism of the College. When sixty or seventy busy men are willing to leave their own activities and for a space of two days listen to speakers on the state of the College and contribute their own discussions on the state of the alumni body there is little danger of flagging interest among the classes or associations.

A range of sixty years and even more was illustrated between the oldest secretary present and the youngest. A wide variety of professions was represented: lawyers, doctors, clergymen, teachers, graduate students and business men in numerous fields. Distant cities sent delegates: Buenos Aires, Chicago, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, with a numerous delegation from New York and the New England cities. But diversified as the callings and the residences of these men were the same spirit was evident in the whole gathering—a live and eager interest in Dartmouth.

There is no more inspiring moment in the college calendar than that of the rollcall of the classes for this Association. Two whole generations of Dartmouth men, according to the ordinary span of human life, rise and state their name and class within the space of five minutes. It is in effect a living symbol of the evolution of the Dartmouth graduate.

With equal interest discussions were followed on the Alumni Fund, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, the Alumni Council, the Selective Process, the Chicago PowWow, and other aspects of the life of the College, whether the listener was a graduate or Civil War days or of the most recent post-war classes. This fund of information and realization of present problems now centers in the classes and local association groups and cannot help but stimulate helpful activity. Whatever of value the secretaries may take away with them after a visit to Hanover, however, they leave a tremendous stimulus and optimism among the resident officials of the College.

The observer from the outside cannot but be in favor of the recent action of the trustees looking toward some definite control over certain features of undergraduate activity. With each reappearance of spring there emerge from places of winter concealment an extraordinary assortment of motor vehicles. However disguised, as sheet-iron torpedoes or packing-cases, their approach is heralded from afar and their diseases occupy a considerable portion of the labor-time of the local garages.

All undergraduates operating motorcars are now required to register them with the Dean and to present a written authorization from the student's father. This action will at least tend to enlist the cooperation of parents and doubtless in certain cases to check the use of cars which are unsafe as well as far from aesthetic.

Equally desirable seems the more explicit statement of the trustees with reference to the building or alteration of fraternity houses. The spirit of emulation between groups and individuals is no less operative among an undergraduate community than in the world at large. The faculty is likely to experience this spirit when classes wish to exceed the record of their predecessors in social events to the point of unwarranted extravagance. This rivalry is perhaps even more to be feared among the fraternities where the example of other colleges is cited and there is danger of each new fraternity house being planned, not only for its utility but also to surpass anything yet found on the Hanover plain. Fortunately this danger, remote though it may have been, seems obviated by the vote of the trustees. The fraternities should be thankful for a provision that protects them aganist themselves and the alumni for action that promises to preserve the comparatively simple New England village they have always known.

The swing of the pendulum on the Campus has of late been calling forth a vigorous campaign on the part of TheDartmouth. The editor finds a too prevalent attitude of superficiality, pose and fear of being natural. He sees this clothed in a pseudo-aestheticism which is far from appreciating the arts in their true values. And finally he would bring back the universal spirit of friendliness and naturalness in all student contacts. He would indict only a small group as affecting the attitude he condemns, but a much larger group as being indifferent to the tendencies he attacks.

The MAGAZINE in its position of detachment can hardly claim to follow the currents of the Campus. It is true, however, that student opinion veers in cyclesfrom generation to generation. The interests of 1925 must be different from those of 1900 and will inevitably express themselves in a different manner. There is undoubtedly more appreciation of aesthetic matters than was the case in earlier years and we are positive that this interest is expressed by the great majority in a reasonable and wholesome manner.

If there is a small group emphasizing false standards of taste and aesthetic values and exerting an influence out of proportion to their numbers the alumni will heartily approve of any measures which may be taken to check the tendency. Those whose observation of the College has been frequent and close will also concur in the feeling of The Dartmouth that the undergraduate body as a whole is as sound as it ever has been and possesses as sane a sense of values as of old. Whatever effect the campaign may have, a thorough examination of the whole matter and a searching of hearts on the part of the students themselves cannot fail to be helpful.

It should be unnecessary to do so, but the MAGAZINE feels that a last-minute word on the pressing necessities of the Alumni Fund may well be uttered. It is of the first, importance at this critical period in the college history that there be no diminution of alumni enthusiasm and of alumni generosity in providing the money with which, for the past few years, the administration has been able to bridge the gap between income and expenditure. The spirit and zeal with which the alumni always respond have come to be recognized as fairly dependable factors. They must be kept so. Without them the things which the College is doing and of which we are all so proud could not be done. As the situation stands, the choice lies simply between going forward on our course and slipping backward again. No true Dartmouth man can have the slightest hesitancy in making the choice to go forward, when all that is needed to guarantee such progress is a maintenance of loyalty and a reasonable readiness to give.

In the few days that remain before the Commencement season it is absolutely imperative to put the Fund across in the usual triumphal fashion. The College relies on it, and it has never relied in vain. This money represents the interest on an imaginary endowment fund, accruing annually, and enabling the administration to close its year without a deficit, after paying all its just debts and maintaining an adequate teaching force under salaries for which one has not to blush with shame— although it is still a fact that Dartmouth doesn't yet pay enough to hold her best men as she develops them. Here's the whole thing in a sentence: The college isn't extravagant—but is sailing just as close to the wind as it can and still hold to its progressive course. The alumni are only asked to enable it to keep on doing that.

So there you are. We know our job and we have every confidence in our pilot. It remains only to make the record for 1925 as creditable as the record for 1924. The MAGAZINE assumes that every one who has always given to the Alumni Fund will continue to do so. It merely reminds such that the time is nearly up and that good intentions need the fruition of performance. If, like the present writer of these lines, you have been postponing the matter, pray do as he proposes—and mail your contribution tonight.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES—MAY 1-2, 1925

June 1925 -

Article

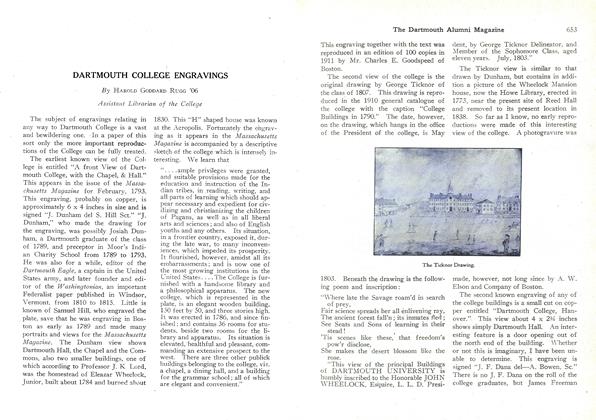

ArticleDARTMOUTH COLLEGE ENGRAVINGS

June 1925 By Harold Goddard Rugg '06 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1925 -

Article

ArticleNEW CURRICULUM IS ADOPTED; A. B. ONLY DEGREE TO BE GIVEN

June 1925 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1917

June 1925 By Ralph Sanborn -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

June 1925 By Frederick W. Cassebeer

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE HONORABLE DAVID CROSS, LL. D.

October, 1908 -

Article

ArticleLEAGUE OF FREE NATIONS ASSOCIATION

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleBalloting for election of alumni councilors is now in progress

May, 1926 -

Article

ArticleStill Going Strong

MAY 1992 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago .... Cry Havoc!

December 1933 By Bill McCarter '19 -

Article

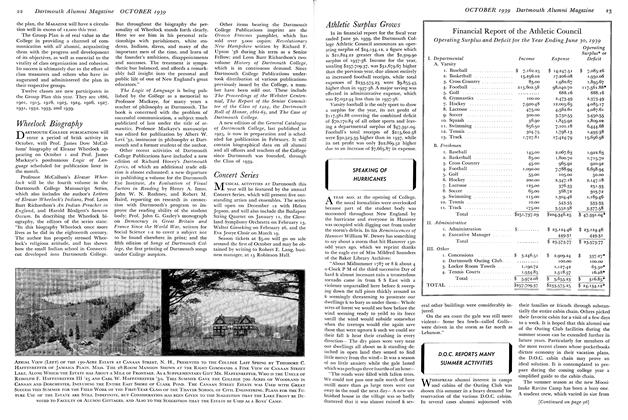

ArticleD.O.C. REPORTS MANY SUMMER ACTIVITIES

October 1939 By Hans Paschen '28t