(From The New York Times')

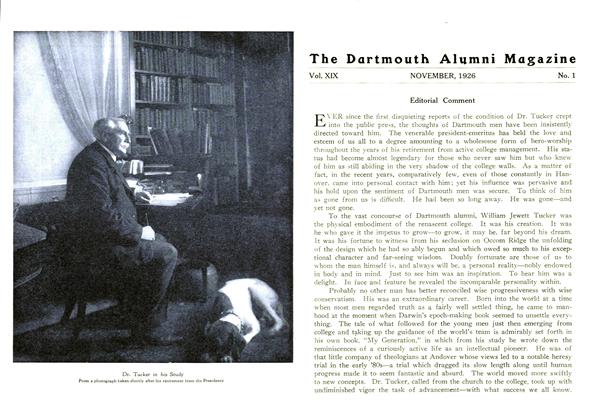

The seventeen years beyond his three score and ten that Dr. William J. Tucker lived in retirement since his resignation as President of Dartmouth College did not dim his achievement in the eyes of those whose memories go back even a little way into the nineteenth century, out of which he came an eloquent preacher and a great teacher into the college world of the twentieth century. Under him the institution of which Webster said, "It is a small college, but there are those who love it," became a large college without diminished devotion. Not only did he lift it out of the financial debt in which he found it, but he put it among the great national institutions of higher education.

In speaking twenty-five years ago of the famous Dartmouth College case, he said that before the college had found a shelter in the wilderness it had been introduced to the Royal Chamber of Great Britain and gained entrance into the most honored families of England, whence it got its corporate name, and that the very animosities and strifes which came in the early days gave to the country the name of a case which was to affect the legal, political and economic interest of the country for many generations. The college "became nationalized by the process." Dr. Tucker, more than any one other man before his coming, won for it a national constituency, comporting with the national fame which Webster's eloquence and Marshall's decision had given it. Indeed, it is now one of the efforts in the new scheme of admissions to insure a national geographical distribution of students while recognizing the demands of its more immediate New England environment and seeking to meet the claims which graduates make for their sons.

It was not merely the physical growth of Dartmouth and the addition of large funds to its resources that came in President Tucker's administration. The curriculum was liberalized, as in other institutions, but with this distinctive purpose: he sought to bring them all under what he called the "idealizing process." He thought "reverently of all knowledge," he insisted upon work as a moral discipline, and he held all intellectual attainments and achievements as tributary to social good. He was not afraid of "useful knowledge." If utility could create the knowing mind, he said that he wanted its aid. He would accept at any time "the moral result of serious thinking on the inferior subject in place of less serious thinking upon the greater subject." Though a the ologian and one of the last of the clerical college presidents, he found no value in the "gymnastics of the old dialectics." Even discourse about God was not necessarily religious or moral. But he believed that his idealizing process in the treatment of all knowledge would result in righteousness.

It was under the leadership of such a liberal, lofty spirit that the Dartmouth College which had been the private school of Eleazar Wheelock in the wilderness, primarily for Indians, and the small college of Webster's day, rose to giant stature even among twentieth century colleges and to a nation-wide "public-minded" service. It is of auspicious promise that one who was as an Elisha to him succeeded, after an interval, to the office of President of Dartmouth. The mantle of Tucker is upon the shoulders of Hopkins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

November 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1926 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1926 By Prof. Nathaniel G. -

Article

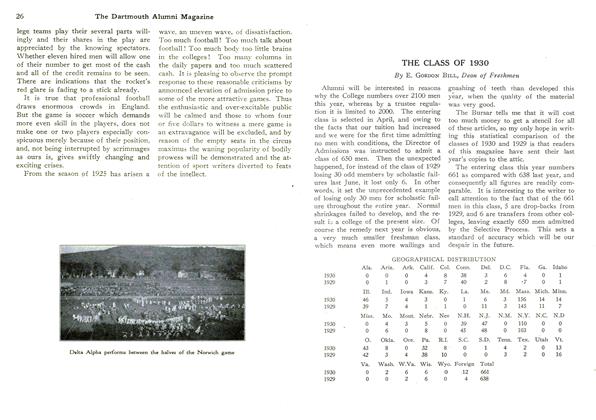

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1930

November 1926 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1926 By Ralph Sanborn

Article

-

Article

ArticleArbiter

December 1948 -

Article

Article"I Am Not Entirely Unaware.

April 1942 By BANCROFT H. BROWN -

Article

ArticleLacrosse

May 1962 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleThe Class of 1933

NOVEMBER 1929 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

ArticleMaster of Arts

August, 1926 By HARLAN COLBY PEARSON '93 -

Article

ArticleShoot the Pager

Novembr 1995 By William Scherman '34