Unhurried, and without ostentation, in the peace and quiet of a north-country village Sabbath, the body of Dartmouth's great leader was borne past the College Green and among the College buildings to its rest. Of him, as of another long before, it could have been said, "If you would see his monument, look around."

Yet, no sufficient monument could be erected were the wealth of the Indies available for this. Bricks and mortar and stone were only minor accessories to the great ends he sought. The true record of his work can never be compiled because the material for this could only be found in the kindled souls, the quickened minds, and the bigger hearts of men who knew him.

Words can no more describe the personality of a great man than they can sound a great symphony or picture a great painting.

Someone at some time may tell with reasonable completeness what President Tucker did, so far as tangible results indicate this. No one can ever know, much less say, how much the intangible factors of life in his time were affected by him. Certainly his influence upon these was very large.

There lies before me a mass of clippings from editorials of the daily press of the country, published since he died. Seldom has appreciative comment upon the achievements of a man, even one stricken down in the midst of his active career, been so widespread. Never within my observation has it been so understanding.

Yet in all that has been written there is no complete picture of this man whose personality and character were as powerful in influence, even, as his extraordinary ability and his indefatigable industry. Phases of his life may be indicated by written or spoken language. The composite man,—that is, the whole man,—was too great, too varied in his genius, and too far-seeing in his vision to be understood entirely or to be described adequately.

President Tucker's coming to the presidency of Dartmouth was for the College one of those occasional pieces of great good fortune attaching to the lives of educational foundations which justifies belief that institutions of good intent and worthy accomplishment become a matter of solicitude to a special and kindly Providence. Full of experience and wisdom, the peer of any thinker of his time, scholarly, cultured and forceful, he would have adorned any postion to which he might have gone, and the prestige of the position would have been heightened and would have won added respect because it was held by him.

He believed in the importance of Dartmouth College to society and he believed in its individual distinction. Thus it came about that to the great heritage which was already Dartmouth's were added those qualities which inhered in him, and which radiating from him, enlivened and stimulated whatever they touched. To the many facets of Dartmouth's life was added that bright and flashing one which reflected and reflects from the College the qualities of his own spiritual and intellectual self. The College of today cannot be explained, nor indeed understood, except as one has some knowledge of the qualities which were his.

He had no pride of opinion which made him willing to ignore evidence which supported beliefs contrary to his own. He never sought to avoid conviction which might lead him away from beliefs pleasing to him or away from preconceived impressions, the substantiation of which he might have wished. No man could ever be more meticulously honest with himself than he was. And slowly the College began to be formed in his very image.

This patrician by instinct and by inclination, by faith made himself a militant leader in defense of democracy. This student by nature and by preference, in the cause of needful service made himself a great administrator. This highpotential mind, capable of analyzing the problems of the universe, stooped without counting the cost and without consciousness of sacrifice to the problem of the individual boy. This soul, simple and humble as that of a reticent child, became in defence of an accepted principle, haughty and unyielding. This heart, naturally as tender as a heart could be, became hard and unimpressionable in the presence of acquisitive self-seeking, insincerity, or bad faith.

To no man of whom I have ever known has it been given to work so pervasive an influence of helpfulness and ennoblement upon so many different kinds of people.

Snobbishness he abhorred, cheapness he despised, and vulgarity he hated. Life as he would have had it lived by mankind would have had nothing soft, nothing small, nothing indifferent in it, but, granted his example could have been made all-pervasive, would have been cleaner, straighter, more unselfish and more free from littleness and meanness than life among men has ever been.

His effect upon those with whom he came into contact was to make them wish to be larger and more unselfish. In his company men outgrew the limitations of their natural dimensions. In association with him it became easy to visualize a world of increased goodness and decreased evil, and to consecrate oneself to the vision.

On that beautiful morning when the body was brought to its place in the cemetery, beneath the guardian pine which stands above his grave, there came to my mind the picture painted by J. M. Barrie in his matchless tribute to the memory of George Meredith.

In this, the great writer whom death had called was represented as sitting apart while his funeral cortege wended its mournful way to Dorking. When the procession had passed into the distance, age and physical infirmity of a sudden began to fall away from him. Soon, with old-time vigor and abounding vitality, he went out-of-doors in the lustiness of youth, and breasted the nearby slope, above which were gathered the hosts of those who called him "Master," for, said Barrie, "When a great man dies, the immortals await him at the top of the nearest hill."

We, on that Sunday, as was meet, observed the ceremony that custom decrees, to mark the break in earthly relationships which death compels, and we grieved. But the truer note of the day was the note of triumph, sounded by those who participated in the various services. Had not the great heart and soul and mind we revered been freed from the trammeling hold of physical weakness and of restraining infirmities?

If, on some neighboring height, beneath the gorgeous canopy of autumn leaves that day, there awaited him those gone before, who called him "Master," what a host was gathered there! Parishioners of the churches under his pastorate in earlier years, whom he had led to knowledge of their better selves; religious leaders and theological students whom he had released from the spiritually stifling atmosphere of dogmatism and outworn creeds; college men to whom he had revealed alike the value of learning, the worth of moral purpose, and the beauty of holiness. They would all have been upon this hill, and many more,—his erst while associates and neighbors and friends.

On these things I thought. I saw again the quick step, heard anew the incisive tones of a kindly voice, felt once more the keen glance of a piercing eye. Then, as thousands of times before, longing surged within me until it became physical pain, for knowledge of how to make my love and reverence known.

Such were my thoughts, yet they were not mine alone. Thinking these things and grieving, I still had joy in the knowledge that I but responded to the sentiment common among Dartmouth men that day. Honor, respect, affection,—so greatly due him,—were his in abundant measure. He still lived in the hearts of men whom he had served and in the life of the College which he had loved.

And we were no helpless and bereft mourners, but disciples of his own. On us it devolved to glorify the immortality of his life and work.

E. M. H

This appreciation of Doctor Tucker was given by President Hopkins at the memorial service in the Old South Church in Boston on October 22.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsMERE FOOTBALL

November 1926 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Lettter from the Editor

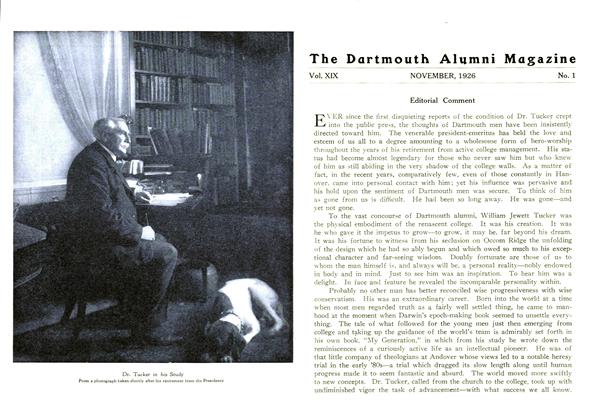

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1926 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1926 By Herrick Brown -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1926 By Prof. Nathaniel G. -

Article

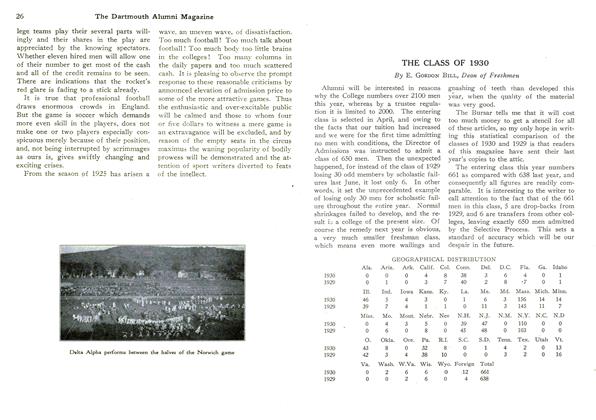

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1930

November 1926 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1917

November 1926 By Ralph Sanborn

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Players Score Again

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleInformal Alumni Carnival, February 21-22

FEBRUARY 1930 -

Article

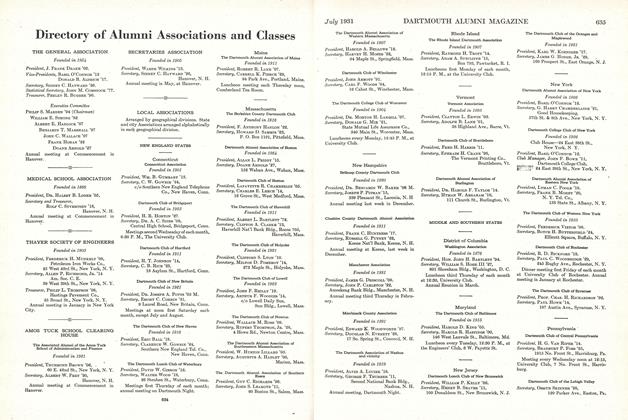

ArticleMEDICAL SCHOOL ASSOCIATION

JULY 1931 -

Article

ArticleTurner Oil Given to College

January 1955 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER INN MOTEL

November 1960 -

Article

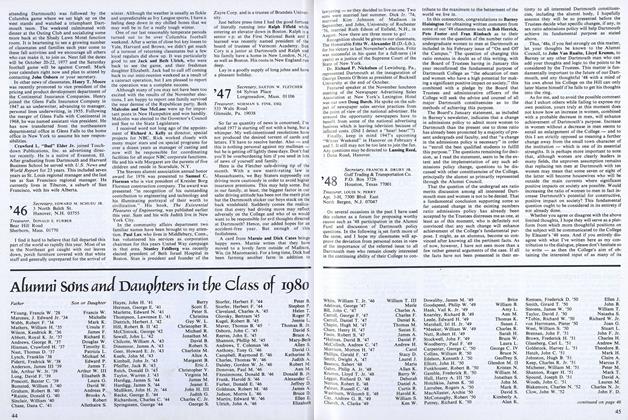

ArticleAlumni Sóns and Daughters in the class of 1980

January 1977