Professor of Comparative Literature

MY TASK IS to try to set forth the advantages and drawbacks, the rewards and penalties, the successes and pitfalls of the profession of teaching. It is assuredly a very large subject. Let me hasten to limit it. Since my own experience has been confined entirely to college teaching—and virtually all to teaching in Dartmouth—l shall not attempt to say anything about the problems which confront the teacher in the primary or the secondary school. Those are questions of which I have only such scant knowledge as comes by hearsay or by analogy.

There are two diametrically opposed views about the dignity of teaching. The first is expressed very nobly in the Book of Daniel: "The teachers shall shine with the brightness of the firmament." The contrary opinion has been tersely and trenchantly put by Bernard Shaw: "He who can does, he who •can't teaches." It would flatter me to think that the Hebrew prophet was entirely correct, and that the epigram of our leading Anglo-Irish satirist was only an ill-natured jibe, prompted by personal spleen. But, in truth, the judgment of the world has wavered rather remarkably between these two statements. On the one hand, education (at least here in America) is fairly idealized and the teacher's repute thereby automatically enhanced; and, on the other side, the teacher himself is undoubtedly looked at askance in the world of practical affairs as something of an incompetent.

This curious blend of respect and contempt appears to be the necessary social aura of the teacher in our country at the present time. It goes back, I suppose, to the old cleavage between learning and life. To be sure, we had not so long ago a President of the United States who had been a college professor, and we have one today who has surrounded himself with a veritable cohort of such men. Whether the net effect of these experiences will be to increase or to lessen the prestige of the teacher is a question which posterity can answer more intelligently than we of today. In the meantime, it is enough to note that the teacher is still somewhat suspect in the world of affairs.

Caricature, which always lags a generation or two behind the facts, used to picture the professor as white-bearded, absent-minded, gullible and help

less—a type which even in those days was as extinct as the dodo. It represents him now as a prig and a pedant, and this conception is even perpetuated in paintings on our college walls here at Dartmouth. Prigs there may be in the profession, but hardly, I think, pedants. Personally, I cannot recall a single real pedant in the range of my observation during the last twenty-five years. If our well-meaning but very uniformed critics were to substitute in their conception pretenders for pedants, they would come uncomfortably nearer the truth. Not that the teaching profession has more high-flown pretensions than any other; but here, as elsewhere, the charlatan is always abroad in the land.

DR. TUCKER ONCE referred to teaching as one of the self-sacrificing professions—meaning that the pecuniary rewards were of necessity relatively limited. The financial heyday of teachers was during the early part of the present economic depression, when salaries remained stationary while the cost of living fell. But that blissful state of affairs did not endure long. In calculating the money rewards of teaching, one has to balance a somewhat meagre, but comparatively sure, salary against unknown opportunities in the so-called open market. The prospects of the latter, frankly, do not look as good as they once did.

Because of comparatively short working-days and more than ordinarily long vacations, the teacher's life cannot fail to make a very strong appeal to those who value leisure. There is plenty of time for reading and reflection. In this respect it may be called an easy life—just how easy it is, only those who have tried a more competitive line of work can adequately appreciate. But this does not necessarily mean that teachers are idle or lazy. There are plenty of them who are as busy as publicans or politicians. But their energies are in great part self-directing; and in that there lies a glorious freedom.

Turning from externals to the true inwardness of teaching, one may safely assert that, for the person who has a real vocation for the job, the major satisfaction comes from the mere imparting of knowledge. If the information is lucidly given and is properly appropriated, then the imparter is a successful

teacher. Every one who enters the profession will have to find out some time—and the sooner he does it, the better—that the problem of education is one of learning and not of teaching. In fact, the best definition of teaching I have ever heard was given by a former professor of mine, himself an excellent teacher. "Teaching," he used to say, "is giving an opportunity to learn." The utmost that even the best teacher can do is to stimulate interest, to ease difficulties, and to act as a general mentor and guide. For the rest, the work has to be done by the pupil. In recent years too much has been said, in my opinion, about the necessity of "personality" in the teacher. The demand is unfortunate because, by placing emphasis on the wrong sort of thing, it tends to make the unessential and the meretricious seem important. Yet this modern demand is apparently here to stay and, willy-nilly, the would-be teacher must face it. Perhaps it has arisen from the suspicion that the teaching profession has been too frequently a place of refuge for those who seek a sheltered existence and who are therefore presumably lacking in robustness and vitality.

Besides knowing his subject well and being able to expound it clearly, the teacher has to cultivate patience and sympathetic understanding. A sense of hlimor also helps, as it does everywhere else in life. There is, of course, plenty of drudgery connected with the work. The unhappy few practitioners who look upon teaching as "the dismal profession" are those who are unable to rise above its stodgy routine. I suspect that they are also the ones who do not really like young people. Not the least of the rewards of associating with the young and liking them is that it helps keep you young yourself.

I WOULD NOT underestimate the disappointments which a teacher almost inevitably meets with in his labors. He will find many students reluctant to work, and not only intellectually incurious but actually opposing a dogged, though perhaps unconscious, resistance to the acquisition of knowledge. He will soon learn not to take anything for granted, and, by that same token, not to expect too much. All the keener will be his delight when he finds that some seed has fallen upon fertile ground. And if he happens to run across former students—perhaps after the lapse of some years—and receive from them the assurance that they not only remember him but can even recall what he said in class, then indeed he will realize that his labors have not been in vain.

WHERE THERE are so many imponderables in the situation, it is obviously impossible to give a categorical answer to the question, Shall I become a teacher? So much will depend on personal predilection and on particular circumstances. But if one were to apply the pragmatic test and judge only by human satisfactions, a rather sweeping generalization might be made. A few members of the profession, who are either manifestly miscast for their part or who have taken up their calling as a makeshift, would doubtless give to prospective teachers the same famous advice that Punch once gave to those contemplating matrimony: "Don't." But, on the whole, the men and women engaged in teaching are, as far as one can observe and compare, just about the most serene and contented group to be found anywhere. And this is saying a very great deal in a world which is not at all remarkable for its happiness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

March 1934 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

March 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1934 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

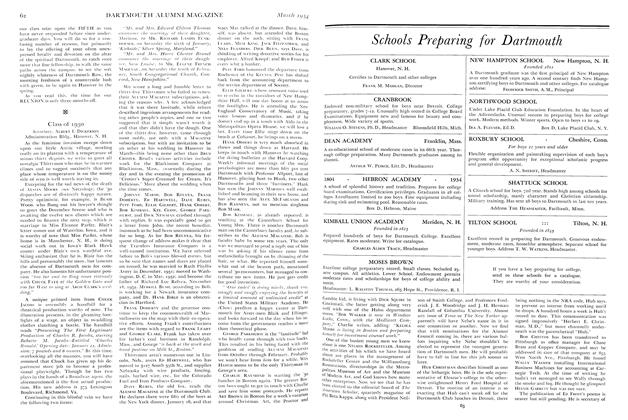

ArticleTRIBUTES TO PROFESSOR LINGLEY

March 1934 By Friends and Associates

William Kilborne Stewart

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE FRATERNITY AGREEMENT

December, 1912 -

Article

ArticleDEATH OF DR. NICHOLS SADDENS ALL HANOVER

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleThe Skier

FEBRUARY 1932 -

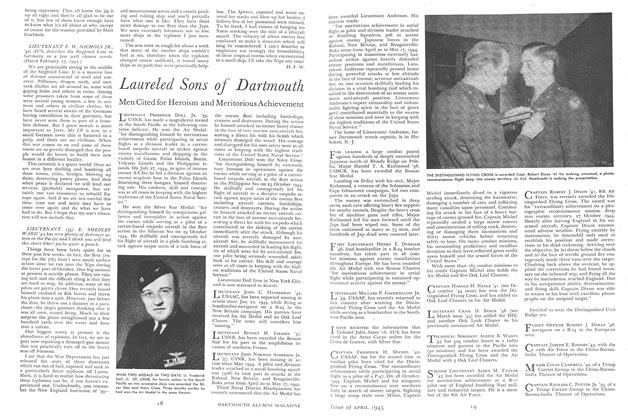

Article

ArticleGOD AND TOTAL WAR

April 1945 By Edward Rasmussen '42 -

Article

ArticleLong Island

FEBRUARY 1968 By MICHAEL R. PENDER '47 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

February 1942 By The Editor