Athletic Applicants

The MAGAZINE has had one or two requests within the past month from inquiring alumni concerning the attitude of the College authority toward students of athletic prowess who may apply for admission requests for a more definite statement of what that attitude is understood to be.

It is not a particularly difficult matter, we believe. The determination of the College is primarily that it shall be guided in its selection of students by a definite purpose to keep the educational character of the institution uppermost. It isn't looking for athletes it is looking for young men to educate and it is concerned first of all to make sure that what such men want is education. If once satisfied of that, the College is certainly not going to hold against them the further fact that some are uncommonly good in sports; and it is not going to withhold from them, any more than from other students not similarly gifted, such assistance as can be given toward getting work of a gainful character to enable the less wealthy applicant to maintain himself.

In other words, the College wants men of the right sort and will do what little it can to make living possible for such as need to help themselves, wholly regardless of athletics or anything else of a subordinate character; but it certainly will not make a specialty of pandering to athletes in order to induce them to come to Hanover, and it will urgently discourage alumni from exaggerating the athletic element in seeking out promising boys to send to Dartmouth. Above all, it will seek to avoid the reception of applicants whose manifest desire is only to adopt that college which will make the highest bid for their services in the ill-concealed hope of improving its teams.

Why not recognize the problem as on the whole simple? The case is very.rare in which one who is personally interested can have real doubts as to what is the dominant motive underlying an application. If a young man of promising intellectual development really wants to come to Dartmouth because it is Dartmouth, and not merely because he fancies it as a field in which to exert himself as a performer on the gridiron, or diamond, or track, one can usually know it; and if the desire is the contrary one that also can usually be known. All one needs is a little unsparing candor. If a boy honestly wants to go to college, and has good reasons for preferring Dartmouth as the college he would seek, let him be a star athlete or not it makes no difference and should make none. The college will do its best in any case to find incidental work for men who need it in order to pay their way. The thing it will not do is play athletes as a sort of preferred class, to be induced to come to Hanover by making competitive bids. Our athletic teams must be made up of players who are players only as an incident to their status as students. Games played and won by any other sort of players are not worth the playing or the winning.

All any alumnus need ever do is be intellectually honest in assessing the cases that come before him. If he knows perfectly well that he is boosting a candidate mainly because that candidate has shown class as a quarter-back who would bolster the college team in a spot where it may need talent, there is good ground for hesitation, even though the candidate is also a pretty good student. If he knows that a boy is being actively pursued by three or four rival college groups because of his prowess on the athletic field and is only waiting to see which one offers the best bid, there is no ground for hesitation at all. Dartmouth can worry along without that boy much better than it can afford to hire him to be a student for that's about what it would come to.

But if a lad of promise is eager to go to Hanover and if you know that his reasons are good, if he would rather go to Hanover no matter how easy it would be for him to subsidize his college course by going somewhere else, then the fact that he is also a promising player in some line of sport is certainly not a thing to penalize.

It's all a matter of realities. Dartmouth wants the right kind of men to spend her time and effort upon and the right kind of men are not in the market for the highest bidders to pick up. If that's the guiding principle for the boy who is looking about for a college, Dartmouth doesn't need him, or want him. As for the alumnus in his estimate of such matters, we don't believe any one ever has a very serious doubt when standing at the bar of his own conscience concerning the bona fides of a given case. When in doubt real doubt it may be best to play it safe. The College is a college; not an athletic association. Its teams are made up of students who are incidentally players, and not of players who are incidentally students.

Building For The Future

One of the things about that new Library which it seems should appeal especially to those interested is the obvious determination this time not to fall into the mistake which has attended certain past erections the mistake of underestimating future needs. One has only to reflect on the fact that College Hall and Webster Hall, two of the most important early buildings in the new plant of the College, are at this moment inadequate to the purposes for which they were intended. It is impossible to consider Webster Hall large enough for the purposes of an auditorium in the present estate of the College ; and College hall, besides being too small for what is required of it, is in addition somewhat below the desirable standard purely as a building.

The lesson of those two outstanding instances is clearly that what building we undertake from this day forward should be undertaken with the determination to foresee more accurately the necessities of the next thirty years at least. Recent statements from our larger cities indicate that the average life of a modern business block has come to be about 34 years; and while there is no very direct basis for comparing such with the buildings of a college or university, it is at least apparent that what structures Dartmouth put up at the start of its amazing expansion, between 25 and 30 years ago, have revealed within that interval their progressive inability to serve as they were originally intended to and part because of later improvements in fire-safe construction and in part because the College has grown so much more rapidly than any one at the time could have expected.

The new Library has in consequence been planned for a definitely growing community, as was imperative in a unit so rigid by nature. One sees the difference between such a structure as a Library, or an Auditorium, and the ordinary laboratory, recitation hall, or dormitory. One may reduplicate the latter ad libitum, but the Library and the Auditorium and perhaps also the Commons do not admit of that sort of expansion. One building has to do the work, and in consequence it is of the first importance that when it is built it be built large enough to handle the work for years enough to warrant the expense. Of course one cannot always tell what the future is going to demand. The donor and projectors of Wilson Hall no doubt felt that they had devised a library building which would suffice for a great many years—perhaps forever. And they had reason to think they had done so, according to the light then available. There has come to pass a greatly amended situation which it is necessary to take into the account.

Speed Up The Playing

The next revision of football rules, according to Mr. Edward K. Hall of the rules committee, is unlikely to make any radical alterations in current regulations of the game, even with regard to the forward pass. There may be, and it is believed there should be, changes calculated to speed up the play and perhaps some amendment with respect to the penalties attending unsuccessful passes. But the tendency which has marked recent years to open up the playing and make it more intelligible to inexpert onlookers is one which most people appear to commend. The average man of today would probably say at once that football is more interesting and easier to follow play by play at present than it was some 25 years ago, apart from the one deterrent factor which we may describe as the excessive delay, or slowing up, of the action. To be quite frank the games as now conducted often tend to drag, and at times approach the point of boredom, because so much time is consumed between scrimmages.

One's mind goes back to the rude old days when there were two 45-minute halves with a 10-minute rest between. In those days the players were almost constantly in action and plays were pulled off in rapid succession. Contrast the situation with the present, in which time is forever being taken out, whilst the playing periods have been cut to four 15minute quarters with a 15-minute respite in the midst of the game. The effect on the men seems to be curiously opposite to what one might expect. It would be difficult to maintain that the harder and faster game of 25 years ago used up the players much more seriously than the more dilatory and better spaced playing does today.

It would be welcome to have such changes in the playing rules as might tend to reduce the idle time—and there is already talk of curtailing the delay due to the huddle system of imparting signals. The fact is that football needs a bit of speeding up. In addition, it is beginning to be felt by many that there is altogether too much of the custom of taking out and putting in players. In baseball, if a player is "derricked" he cannot return to the game. In football a man may go out and in, ad lib., at the behest of the sideline strategists in command of the play perhaps for the performance of a single operation, like kicking a goal, in which process that player reveals his sole proficiency.

One hesitates to say so, but there is bound to seem that the English view has a great deal to commend it when it holds that a team once started in a game should continue unaltered, barring injuries, to the end. This is totally at variance with the American theory which remakes teams to no end as the game proceeds and as new situations develop; but there is something to be said for it, just the same, from the viewpoint of pure sportsmanship.

At all events the present writers incline to believe that the American system of making every game the subject of intricate strategy and of what the sporting writers sometimes call "politics," through the constant substitution of new talent, has gone entirely too far for the pleasure of the spectators, whatever be thought of it from the sporting point of view or as an ethical question. Certainly the football games of the past season dragged too much for pleasure, and anything that will increase the speed of the play will be welcomed by thousands.

Undergraduate Wisdom

Just what was the basis for selecting delegates to the recent conference of American college students in Milwaukee is not recalled, but some rather interesting resolutions were announced in December as having been adopted by that body, coupled with the statement that the opinions voiced therein would be brought to the attention of President Coolidge and the Congress—a step which it is to be hoped both the White House and the Capitol will appreciate. These resolutions had to do in part with war, in part with economics, in part with politics.

Out of several hundred delegates, it is stated that only 95 adopted the old-fashioned view that if their government became involved in a war it would be their duty as loyal citizens to bear true faith and allegiance to it. On the other hand 327 valiant souls declared that they would not support any war of any kind doubtless preferring the pleasant martyrdom of going to jail for their beliefs; and 740 "affirmed that, while they would not go quite so far as the others, they would only promise that they would support their government in "some wars," in case they approved the underlying cause, reserving the right to withhold allegiance if they disapproved. A fair-sized fraction something like 300 if memory serves made no statement at all.

In the realm of economics there appears to have been substantial unanimity in the assertion that our present capitalistic system of industry is all wrong since it is "based on production for profit instead of on production for use." A few, however, held that the current system at least seems to square "with the general doctrines of Jesus." In another resolution, these sapient youths upheld the idea that there ought to be more control of industry by 'workers." In short, pretty nearly everything was done and resolved that one would naturally expect who knows anything about the sort of students likely to attend such a conference as delegates. The unkind cut is to find the HarvardCrimson referring to these hopeful young reformers as "half-baked and incapable of being anything else" in urging reforms which they do not at all understand, after wholly inadequate experience and insufficient study. The Crimson appears to feel that any undergraduate in college must be ill equipped for any such discussion, and that the bodying forth of such hazy ideas involves a high degree of presumption. Many will agree, though some will mitigate their resentment of the presumption with a saving salt of amusement.

The whole thing is so amazingly in character with the cocky self-confidence of the rudimentary "Intellectual," which flowers so luxuriantly in these days in academic soil along with new verse, cubist art, explosive new ideas on sex relationship, matrimony and communism. The ideas voiced may be worthless—it is likely to seem to any person of full age and experience that they are so—but it may be important to remember that, worthless or not, they are significant of the times. This is an age in which undergraduates are being encouraged to speak out and tell the world what they think so that it is perhaps pardonable if the immature delegate to a conference of boys and girls scarcely old enough to vote, fancies it to be his duty to bring his thoughts to the attention of the president and Congress. The sensible thing might be to ask undergraduate opinion concerning things as to which such opinion might be conceived to have a real value and to represent conclusions based on experience and observation. For example, good might well flow from the recent experiment at Dartmouth in which a representative body of undergraduates was asked to set forth its ideas of the proper scope of college training and the best means for serving it. But when it comes to oversetting the accumulated experience of thousands of years in economic matters, at the whim of a conference of young students assembled at hap-hazard from various colleges, there is hardly need of any great and solemn referendum to register the public's judgment of the idea.

Whether or not the colleges have gone rather too far in flattering the young into a sense of exaggerated importance as sources of social and economic wisdom may be left untouched. They have gone pretty far, and the fashion of the day is to be radical rather than patriotic. Witness the 95 who said they'd support any war that the government undertook, as against the 327 who'd rather go to prison and the 740 who propose to be their own judges of whether to be loyal or disloyal by the ordinary civic standards.

The gay young amateur bolshevik of 18 or 22 years is likely to simmer down before he has been very long out of college and his resolutions at the time of his 40th reunion would probably be of a very different tone. But by the time one is ripe for a 40th reunion there will be still more all-wise youths ready to elbow aside the theories of the oldsters and proffer still more and newer wisdom for the guidance of presidents and Congresses yet to be. Is this at all new ? Reflection will probably convince any one that things were very like this in his own undergraduate day—with the vital difference that no one in older years cared tuppence what undergraduates might think, and very frankly disregarded them as too young to have ideas of very great value. Student conferences weren't common then.

The always refreshing Romeyn Berry, writing in the Cornell Alumni News of some other outburst of undergraduate curiosity as to higher things, sums it up by saying:

"That sort of thing bewilders an old grad who was brought up to , believe that the whole duty of a freshman was to keep his mouth shut and his pores open and to pass his work and that serious problems, like cuts in the leg, would cure themselves if you did not pick them.

"Colleges are likely to become dreary places if undergraduates start going in for education, but they seem to be doing it. There is nothing for the old grads except to accept the situation and to thank God that they themselves lived in another day."

That's more or less true. It is even more true as applied to these self-appointed saviors of society from the college classes who go in, not for education, but for instructing others as to just where they get off. Away with an economic system that seems to square fairly well with the teachings of Jesus! What we want is a system that squares with the teachings of Lenine—and how terribly sure we are of this while still in college and being supported by our parents! "Father and mother pay all the bills and we have all the fun" was once a popular ditty. But there always was a suspicion, even in the elder days, that the old folks didn't know much, although they weren't so keen on hearing our views as people seem to be now.

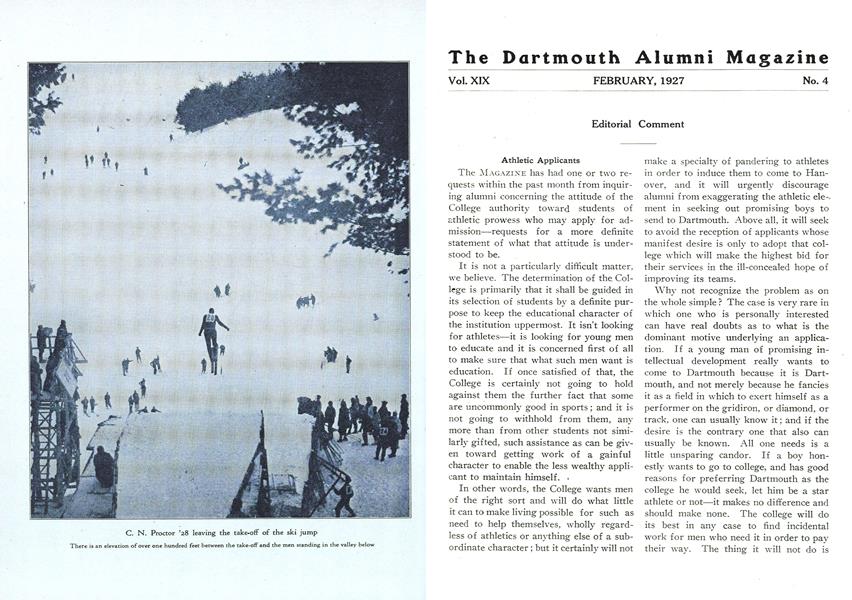

A Carnival ice pillar

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSARAH CONNELL GOES TO THE DARTMOUTH COMMENCEMENT OF 1809

February 1927 By Dr. James A. Spalding '66 -

Article

ArticleA POLISH UNIVERSITY TODAY

February 1927 By Professor Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

February 1927 By Frederick W. Cassebeer -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NEWS

February 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

February 1927 By Herrick Brown

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JANUARY 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorIn Keeping With This Month's Cover Story, The Review Barks Up Dartmouth's Tree.

MAY 1992 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Real World

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood