The Function of the College

In their welcoming speeches to the great rush of incoming students, the college presidents are just now sowing the seeds of wisdom in the minds of our future "intelligentsia." If but a half of the grain falls on good ground, and is well watered by subsequent instruction, we shall have wise leadership when these young men and women come to their full intellectual and dynamic powers. President Lowell tells the Harvard cohort that they must cultivate individualism. The university, he says, does not want to make its students all alike. The word is timely. We tend in this country too much to standardization. It is not for the Harvard hallmark that men should go to Cambridge, but for an effective training of their individual powers.

In reading over the reports of these presidential addresses, we find the most suggestive quality in the words of President Hopkins at Dartmouth. He boldly ventures to take up the question of the leadership of educated men in connection with our "American" doctrine that the voice of the people is the voice of God. We may have, Dr. Hopkins thinks, an undiscriminating confidence in this infallibility of public opinion; we "demand that our legislators, our courts, our churches and our schools shall be subject to the popular will of the time, however ephemeral or capricious this may be." We may well question, the president of Dartmouth intimates, "whether man's enlarged dominion in the fields of physics and chemistry has not introduced a hazard to the social state beyond man's ability to control." In other words, the "vox populi" needs intelligent direction as much as, if not more than, it ever did. The implication is that it is the function of the college to train leaders who know the demand of the time in this respect. The college must know the people, know the spirit of the time, and know how that spirit is to be wisely led. And this is Dr. Hopkins' conclusion: If the only options available to this college were to graduate men of the highest brilliancy intellectually, without interest in the welfare of mankind at large, or to graduate men of less mental competence, possessed of aspiration which we call spiritual and motives which we call good, I would choose for Dartmouth College the latter alternative. And in doing so I should be confident that this college would create the greater values and render the more essential service to the civilization whose handmaid it is.

The "greatest values" these are what the colleges are all after. To attain them, even to know them, is a great task. Such an address as this shows how far our higher institutions have progressed beyond Greek roots and the infinitesimal calculus. They are becoming allied with human growth. The colleges have themselves a lot to learn—and their highest function is to carry their students along with them in the learning of it.—The Boston Transcript.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTODAY'S RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE

November 1927 By President Ernest M. Hopkins -

Article

ArticleDICK'S HOUSE

November 1927 By Eugene Francis Clark '01 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

November 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

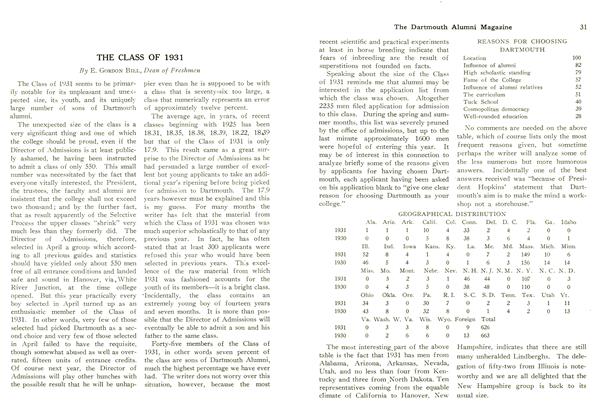

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1931

November 1927 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CLUB OF DAYTON, OHIO, ESTABLISHED

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in Surinam

February 1942 -

Article

ArticleReplacing Old Faithful

December 1975 -

Article

ArticleLanguage Change

March 1950 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleFreshman Football

December 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleAuthor and Sophomore

March 1961 By TED BREMBLE '56