by Alexander Dean, 'l6. Associate Professorof Dramatic Art and Literature, NorthwesternUniversity, School of Speech. D. Appleton andCo., 1926.

Reviewed by E. B. Watson The Little Theatre in America can no longer be regarded as a passing fad. The scores of volumes telling us how to conduct it prove the existence of a large group of widely experienced amateur producers and a host of others eager for advice about the smallest technical details of Little Theatre organization and production. Mr. Dean in the present volume has contributed one of the most complete of these treatises and, in its practical aspect at least, one of the best. Admirable as his work is in all that pertains to the technique of the stage, to business organization, and to community relationships, his selfrevelation as a devoted Thespian is still more engaging, for playing around his more practical matter are lights and shadows from which the reader unconsciously constructs a mental autobiography of one of the most successful creators of the American Little Theatre.

This fetish of earlier times has lost much of the magic of its intellectual pose and its former exaggerated insistence upon the exotic and has developed instead a sincere amateurism, which, as Mr. Eaton remarks in his preface, unlike that of our other arts, notably music, is rapidly becoming self-expressive: "In our Little Theatres we ourselves are not only audience, but actors, scene painters, costume designers, even increasingly playwrights." This aspect of the Little Theatre has evidently claimed Mr. Dean. He lays down as the chief article of his creed that his theatre lives for and by its amateur spirit. He takes a refreshingly reactionary stand against those who are now urging professionalism as the culminating stage in the Little Theatre triumph. Mr. Dean's amateurism, however, is balanced by a sane demand that it be financially self-supporting; but he is concerned only with "actors who play for the love of it rather than as a business" and "with the production of plays and advancement of the drama for a definite audience and at definite periods of time". Among these "definites", those of school and college rank high: "It is to the ambitious director of school dramatics", says Mr. Dean, "to whom my heart especially goes out". To the director, then, he offers a helping hand. He has convinced himself that most Little Theatre mortality is due to lack of knowledge of the technique of management, and this knowledge he modestly supplies in generous portions, not as lecturer, but as friendly confidant opening up' his horde of hard earned experiences. A list of his various successful managements from Dallas, Texas to the North Shore Theatre Guild of Chicago would attest the immense value of this experience, but the author nowhere parades them.

Although he evinces not only wide familiarity with dramatic literature and with all that is vital in the newer stage art of our day, his policy as a director is marked by a wise conservatism, at least so far as his dealings with audiences are concerned. In this respect he seems in accord with the policies of such distinguished community theatres as that at Pasadena. He has learned that in order to get his public to accept what he wants to give them he must first give them what they think they want—the commercial success. This baiting of the audience has more than justified itself, for, in the long run, what the public wants, Mr. Dean confidently asserts, "is, as I have constantly found it, the best."

For readers who are not Little Theatre zealots the book has much interest especially on the pages devoted to a study of the decline of the theatrical "road," the rise of New York as a dramatic center, and the response of the Little Theatre to the new demand throughout the country. All this is solemn dramatic, not to say social, history and merits perusal by students other than those of literature and the stage.

Mr. Dean comes roundly to the defence of Little Theatre activities in schools and colleges. He finds them importantly educational quite apart from their obvious and more generally recognized function of stirring student interest in drama as a living art. "Our younger generation," he argues, "is too content with inertia and idleness, or activity which accomplishes little or nothing. They, for the most part, look on events in life—a few leaders achieve—but the majority look on school contests, on the theatre, on the radio, on the movies, and on life. Between times they hang around doing nothing, or they take a joy ride. They dance and they dance, and know nothing of the pleasure and satisfaction of achievement". In College theatres Mr. Dean sees "a wonderful opportunity to reach the coming generation." As much of our mental training fails to do, it makes necessary "the creation of a policy, an idea or ideals—the working to execute that plan", thus constituting a valuable lesson that would later be valuable in any walk of life.

Upon such preliminary laying of foundations Mr. Dean constructs an exceedingly well proportioned exposition of the workings of a Little Theatre from its inception as idea to its fulfilment in a vigorous self-supporting community playhouse. Nothing is forgotten from the telephone number of the. subscriber to the director's handling of late-comers at rehearsals. Individual experimenters might differ with Mr. Dean as to policies, principles of play selection, and methods of stage management or discipline, but all would, I believe, admit that he has plotted a thorough and consistent chart which must be invaluable to any sincere seeker in the maze of the community theatre—Land where is there a more perplexing labyrinth ? The authenticity of his advice attested by his wide and most successful experience in Little Theatre founding and management is apparent on every page. This is no text-book of dramatic theories it is a handbook of dramatic accomplishment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

May 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1927 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

May 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

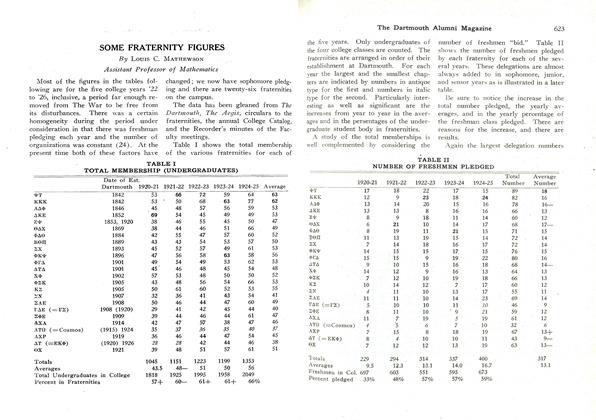

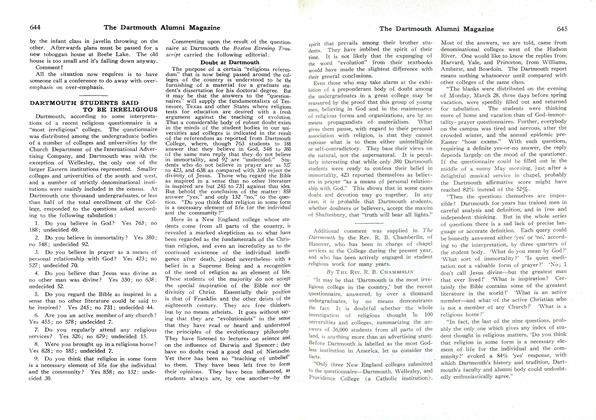

ArticleSOME FRATERNITY FIGURES

May 1927 By Louis C. Mathewson -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS SAID TO BE IRRELIGIOUS

May 1927 -

Class Notes

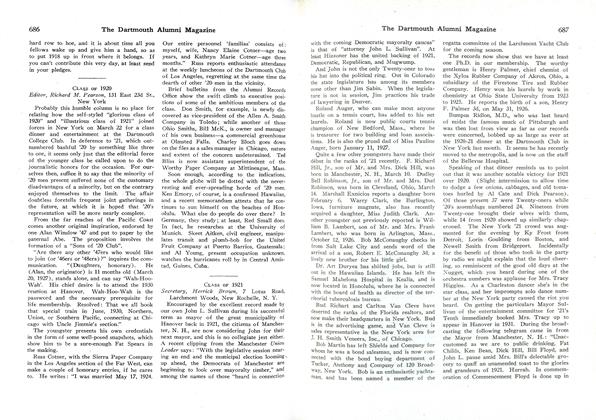

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1927 By Herrick Brown

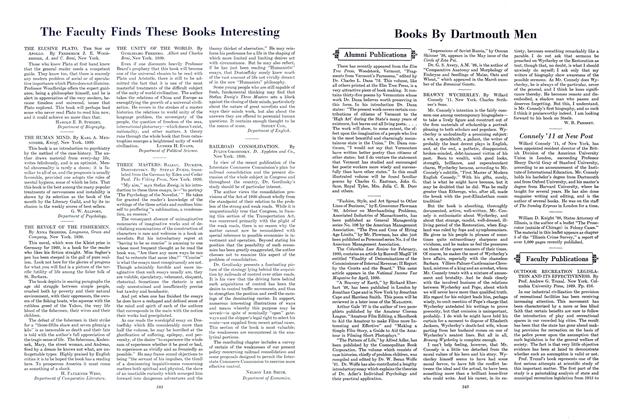

Books

-

Books

BooksConnely '11 at New Post

JUNE 1930 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

October 1956 -

Books

BooksYES, MY DARLING DAUGHTER.

June 1937 By Benfield Pressey -

Books

BooksNORTHERN LIGHTS: WRITERS FROM THE UPPER VALLEY OF VERMONT AND NEW HAMPSHIRE.

June 1974 By CLAUDE G. LIMAN '65 -

Books

BooksRENAISSANCE LITERARY CRITICISM,

November 1945 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksRELIGION AND CONDUCT

AUGUST 1930 By William Kilborne Stewart