By Charles B.McLane '41. New York: Columbia University Press, 1958. 310pp. $5-50.

It has often been assumed that Communist Parties abroad are mere puppets of Moscow and that their actions are always determined by the Kremlin puppeteer. It is also often assumed, somewhat contradictorarily, that the Chinese Communist Party is likely at some point to break with the Soviet Party and follow an independent course.

By examining carefully the nature of the relationship between the Soviet and Chinese Communists in the period 1931 to 1946 (that is, prior to the coming to power of Chinese Communism) Charles McLane contributes to our understanding of these crucial problems and of the nature of Sino-Soviet alliance. This study reaches two extraordinarily interesting conclusions: 1, that the Communist Party of China remained largely free of Soviet control during this period (Mao's rise to leadership was for instance not the result of Moscow interference in internal party affairs); 2, that, nonetheless, the Communist Party of China in most important respects followed the line of Moscow in Chinese and international affairs.

Often the policies followed by the two parties were parallel rather than coordinated, and differences of emphasis and interpretation were evident. Contrary to popular impression, however, McLane finds no serious diversity of view, even on matters of ideology, in which Mao is often regarded as an exponent of an independent Chinese Marxist doctrine.

These and other conclusions are based on a prodigious amount of research, mainly in Russian materials, but also in sources available in English, including translations of Chinese Communist documents. As well as using libraries in the United States from Stanford to the east coast, the author even conducted several interviews in Tokyo and Hong Kong to fill in crevices in his study. Taking nothing for granted, McLane has investigated every scrap of evidence available in languages known to him, and has engaged in sober, cautious speculation about some of the more confusing and ambiguous aspects of this complicated history. Where things still remain obscure, he is not afraid to say so. It is his belief that examination of Chinese sources would not alter the conclusions fundamentally, a belief that can only be verified when some other scholar produces an equally careful study of these sources.

The study also throws considerable light on the nature of Soviet policy in China during this period and on the process of Soviet foreign policy formulation. Russian attitudes towards the Chinese Soviets after 1930, the United Front after 1935, the war against Japan, the evacuation of Manchuria, and the negotiations between Chiang Kaishek and the Communists down to their breakdown in 1946, are all examined and interpreted. From this analysis, it appears that even in so important a matter as the question of support for a Chinese Communist revolution, Soviet Russian policy was not as inflexible and predetermined, nor as foresighted and consistent, as is usually assumed. Soviet policy, in this case as elsewhere, seems not to be a mere reflection of ideological preconceptions but to take into account Soviet practical interests under changing conditions.

In one important episode McLane describes an apparent conflict of policies between different departments of the Soviet administration. He also indicates that Soviet attitudes were sometimes reactions to American policies rather than unchanging policies laid down on the basis of permanent Soviet objectives.

The author does not himself draw any conclusions concerning American policies toward Soviet and Chinese Communism. His case study does, however, indicate the necessity of a flexible American policy, not a rigid attitude dictated by our own ideological preferences and false assumptions concerning Soviet ideological preferences.

Although the study suggests the strength of Soviet-Chinese bonds of unity, and the unlikelihood of serious splits in the alliance, it may also be concluded that Chinese Communist policy is in part also a reaction to American policy, and may shift in accordance with changes in our own attitudes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Nasties Upset Since Bunker Hill"

February 1959 By COREY FORD '21h -

Feature

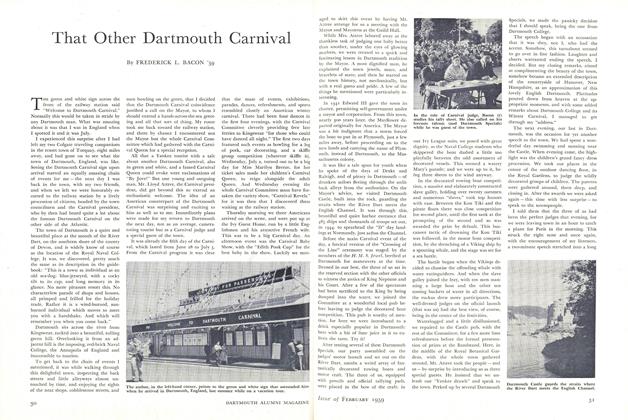

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

February 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

February 1959 -

Feature

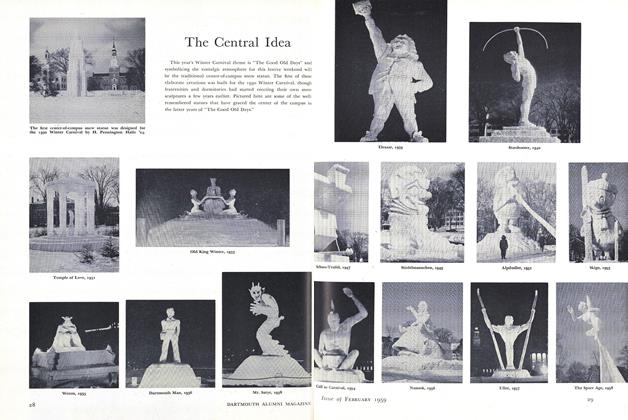

FeatureThe Central Idea

February 1959 -

Article

ArticleSome Consequences of Inflation Psychology

February 1959 By COLIN D. CAMPBELL, -

Article

ArticleShould We Blame the Unions?

February 1959 By MARTIN SEGAL

Books

-

Books

BooksMr. Elmer E. Smead

November 1936 -

Books

BooksShelf Life

May/June 2002 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN HOLLAND

November 1950 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTRAVELS IN NORTH AMERICA IN THE YEARS 1780, 1781, and 1782.

MARCH 1964 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksJOHN DEE: THE WORLD OF AN ELIZABETHAN MAGUS

JUNE 1972 By JAMES A. EPPERSON III -

Books

BooksA PHILOSOPHER LOOKS AT SCIENCE.

MAY 1959 By R.W. CHRISTY