COSMIC ECOLOGY: THE VIEW FROMTHE OUTSIDE IN

by George A. Seielstad '59University of California Press, 1983.190 pp., $24.95 cloth.

Ecology is "that branch of biology which deals with the mutual relations between organisms and environment," but it is common practice to confine the scope of those relations to earthy habitats. A sense of impending catastrophe has recently raised the level of public awareness regarding the balance of those systems and processes that maintains the status quo, and yet there is little evidence of our showing any inclination to temper our meddlesome impulses. Human history with all its spectacular intellectual achievements is blemished by an unremitting plundering of the earth. When numbers were small and weapons of destruction were primitive, the consequences of witless exploitation were hardly noticeable. Now, they are everywhere apparent. A host of nature's balances have already been upset to a point of no recovery. And most alarming the tempo of change is quickening. Although we are a very late arrival on the list of living creatures, the disproportionate development of the human brain has brought us rapidly to a critical moment in our evolution, because it is in the nature of intelligence to accelerate change at a rate far outstripping the usual pace of biological evolution.

No organism is a merely passive reactor to its environment, but among all creatures our species is unique in having developed its influence globally, and with effects that can lead to its own extinction. Full of knowledge but wanting in understanding, we have become the victims of our own cultural evolution. The ancient wisdom by which we acknowledged, as an axiom, a harmonious existence with our environment has been forgotten. A reaffirmation is now essential but a thinking population wants also to know the rational foundation on which such a truth rests, and in this search it helps to expand the ecological argument to the cosmic scale. This is the objective of George Seielstad's admirable book, Cosmic Ecology. The message is grand, but the author is in such complete control of his subject that he can be both brief and clear, even in explaining matters that are technical and difficult. Reading this book is made all the more pleasurable not only by its handsome format but also by Seielstad's easy prose, which is both graceful and apt.

The author has been a practicing astronomer for two decades, and when he says in his preface that we should all wonder whence we came, he doesn't mean it with the usual anthropocentric myopia. He means to start at the beginning, with the "Big Bang," because from then on everything is connected. That is what we have to understand. To lead us along the chain of events from the creation of the universe to the creation of the earth, to the creation of life, and finally to the human species and the immediate question of its fate, Seielstad needs only 162 pages. His perspective is revealed by the fact that biological evolution is not taken up until page 105. All that precedes sets the stage by treating atomic evolution, chemical evolution, and speculation about the existence of life on other worlds (which Seielstad thinks probable because if the universe is infinite in extent, nothing can be unique, every conceivable variation must exist, and life somewhere else is, therefore, logically likely). He emphasizes the continuity of inanimate and animate evolution in which we again, we in its broadest sense are children of the cosmos: "That we are direct descendants from ancestral stellar giants establishes a tie between us and those nightly beacons from which we had heretofore seemed wholly divorced. The iron in our blood, the calcium in our bones, even the gold fillings in our teeth, are sprinkings of Stardust manufactured in, and explosively spewed from, physical predecessors that now exist only as galactic memories."

How resoundingly this modern message echoes the words of other sages in other times. Compare, for example, the teaching of a neo Confucian philosopher, Chang Tsai from the eleventh century "My body is of the same substance as that of heaven and earth; my nature is of the same organizing principle which controls heaven and earth." We moderns have broken that bond between life and its setting. Seielstad says, "Rather than passively (even gratefully) accepting the offerings of his environment, man learns to manipulate it actively to suit his specifications." It is that manipulation which has brought us so quickly to the present. The catalytic influence of collective intelligence has led us to invent skills at a rate far exceeding the development of wisdom in using them.

After elaborating on the frightening consequences of unrestrained progress, Seielstad confronts the crucial issue: What shall be done? He sees that the greatest threat "may be not biological extinction, but, instead, an extinction of the cultural values that define our humanness." Nonetheless he is optimistic and envisions a new kind of evolution, described as "participatory and collective," one which replaces the "unbridled self-indulgence" of biological evolution with one "dominated by cognition." He expects that the future will be selected consciously rather than naturally. Whether we will choose the right courses of action remains unanswered. Can we cure ourselves of the syndrome of what Barbara Tuchman calls "cognitive dissonance" an unwillingness to listen to facts? The history of humanity does not promise a sudden mending of our short-sighted and selfish ways. The record of the past strongly suggests that we act more in response to what we feel than to what we know: and whether we have the capacity to project conceptually in time is debatable. Only the reality of the moment seems to be appreciated. We can ill afford the luxury of despair, but perhaps some frustration is pardonable.

The authors' preface warns the reader not to expect any detailed solutions; the book's purpose is only to be informative. The last section is therefore very brief, but in it Seielstad drops the encouraging hint that another book will follow, and that it will treat more fully his ideas about a remedy for our predicament.

"Cosmic Ecology" is an important subject which could easily lead to a ponderous and unreadable book for all but the specialist. George Seielstad, in no way intimidated by the vastness of his subject, has written aft instructive book notable for its clear exposition. Anyone interested in understanding the significance of John Muir's "When we try to pick up anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe" can do no better than read Cosmic Ecology, and those who think they are not interested should read it to find out why they ought to be.

Marsh Tenney is the Nathan SmithProfessor of Physiology in the Dartmouth Medical School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

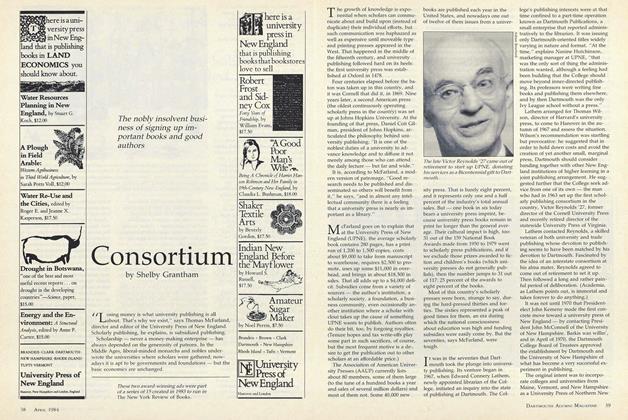

Cover StoryConsortium

April 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHanover Sabbatical

April 1984 By Robert Conn '61 -

Feature

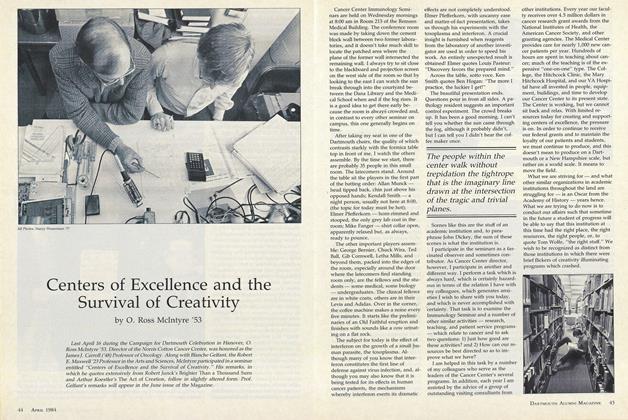

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

April 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

Feature

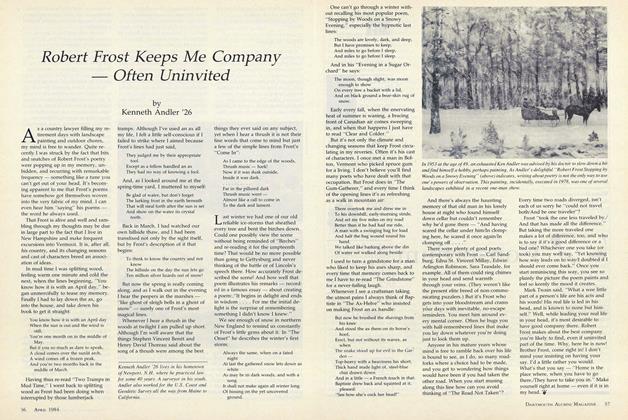

FeatureRobert Frost Keeps Me Company Often Uninvited

April 1984 By Kenneth Andler '26 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

April 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1984 By William G. Long

Books

-

Books

BooksFunny Latins Chileans Are Not

May 1975 By BERNARD E. SEGAL -

Books

BooksTHE PLANS OF MEN

July 1940 By C. N. Allen '24, Harold G. Rugg -

Books

BooksROBERT FROST: FARM-POULTRYMAN

FEBRUARY 1964 By C.E.W. -

Books

BooksBANK LOANS TO SHOE MANUFACTURERS,

May 1949 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Books

BooksWhen Life Begins

June 1962 By HE MILFORD (N. H.) CABINET -

Books

BooksQUEST FOR MYTH

December 1949 By Vernon Hall Jr.