(From The New York Herald-Tribune)

President Ernest M. Hopkins, of Dartmouth College, would revolutionize intercollegiate football. He offers three suggestions, the limiting of participation in football to sophomores and juniors, the development of two varsity teams and coaching by undergraduates. His aim is to establish a better balance between academic endeavor and athletic activity and to eradicate the commercialism which clouds intercollegiate sports.

His third suggestion has much in its favor. The benefits that might accrue from the first and second changes are not as clear. But much more important than the specific proposals is the fact that Dr. Hopkins, the head of a college which has had a distinguished football record in recent years, should feel it necessary to suggest extremely radical changes in the conduct of the game. In our judgment his action is fairly conclusive evidence that all is not well in intercollegiate football.

Dr. Hopkins's suggestions are indicative of the dissatisfaction which exists in the undergraduate body. Here and there, notably at Harvard, Williams, Amherst and Wesleyan, the students have been showing signs of unrest, of a change in feeling toward intercollegiate com petition, of a contempt for the ballyhoo and commercialism which have turned friendly competition into public spectacles and youthful athletes into gladiators. Dr. Hopkins has our full support in his campaign for change, but we doubt whether all his suggestions will bring the best results.

What we need in American intercollegiate circles is a bit more of the spirit to be found at Oxford and Cambridge. Recently we had the report of Dr. Howard J. Savage, who made an exhaustive investigation of athletics in British schools and colleges for the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. In a word, he found that in England sport is regarded as an incident in school and college life. It never assumes the proportions of a life and death affair. Failure to make a varsity team is not the death knell to a college career. The president of the Oxford Union commands as much respect as the president of the Oxford Boat Club or the Rugby team. The afternoon is given over to recreation and the undergraduate can do as he pleases—play football, golf, paddle on the river or walk or study.

President Hopkins's proposal to limit undergraduates to two years of intercollegiate football will strike most observers as an extremely radical reform. Certainly, if the true spirit of amateur athletics prevailed in American colleges no such restriction would be dreamed of. A freshman is stroking one of the English varsity crews this year. A senior should be at the height of his physical development. Windebar him from the football team? The war on "tramp" athletes should go on. The colleges should admit only students who seek admission because they want a college training, consisting of cultural, social and athletic development. This is the real goal.

The second suggestion is a compromise facing a number of practical objections. With two varsity teams, will the ballyhoo he lessened or increased ? Suppose two Dartmouth football teams defeat Harvard the same afternoon. Will there be the gain along the lines President Hopkins hopes to advance?

We see no objection to the football teams or any other teams being coached and directed by undergraduates. Much gain is likely. Incidental, we believe that a professional trainer should be retained. It is too much to ask an undergraduate to keep his eye on the physical condition of his candidates.

In the end the undergraduates will solve their problem. We believe that they are capable of conducting their competitions in a sane and rational way. In the mean time such suggestions as these put forward by President Hopkins are a great aid to debate and clarification of views. The greater the number of college men participating in sports the better it will be for the colleges and the country.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AND CHOATE IN COLLEGE

May 1927 By Herbert Darling Foster '85 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1927 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

May 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

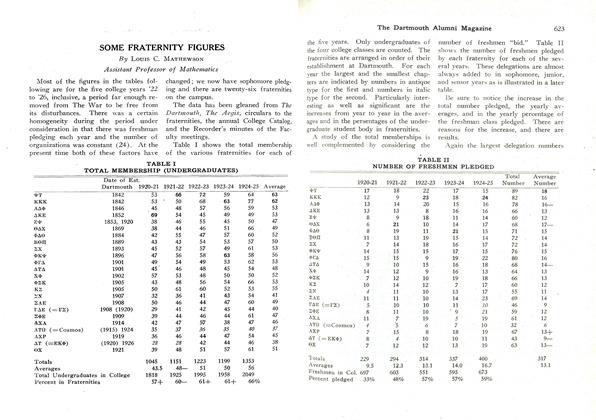

ArticleSOME FRATERNITY FIGURES

May 1927 By Louis C. Mathewson -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS SAID TO BE IRRELIGIOUS

May 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

May 1927 By Herrick Brown

Article

-

Article

ArticleMAINE ASSOCIATION WEEKLY LUNCHEONS

November, 1922 -

Article

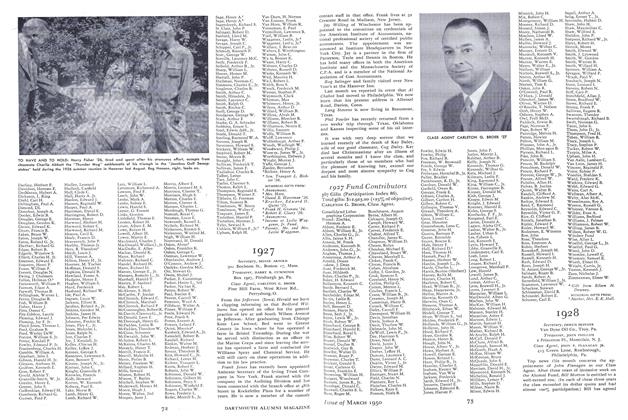

ArticleTO HAVE AND TO HOLD:

March 1950 -

Article

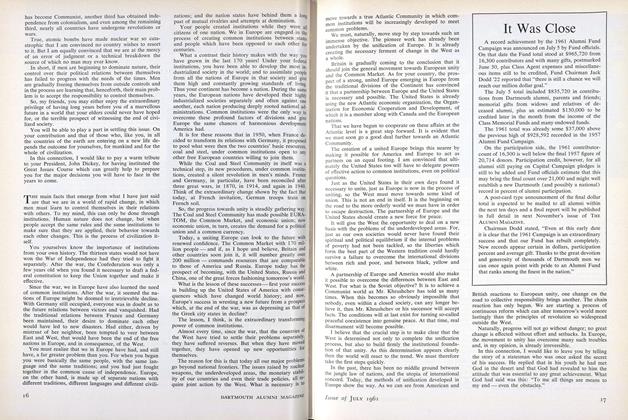

ArticleIt Was Close

July 1961 -

Article

ArticleAfternoons With Frost

October 1973 By FIERMANJ. OBERMAYER '46 -

Article

ArticleFamiliar Ring

December 1994 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

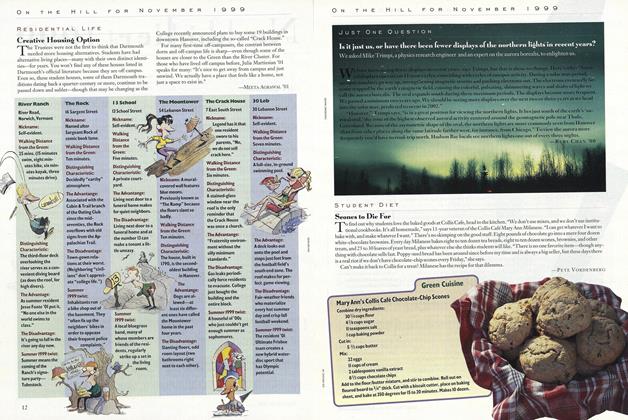

ArticleScones to Die For

NOVEMBER 1999 By Pete Vordenberg