In response to the demand of the alumni expressed atvarious association gatherings and brought bach to Hanover by the men who go out to speak to such meetings theAlumni Magazine is presenting to the alumni a resume ofthe intellectual work of the College through the heads of thedepartments in the College or through men delegated byeach department to present its case to the alumni. This seriesof articles will give to the alumni a general idea of some ofthe departments of the college and some of the phases ofintellectual life touched upon in each department. In thisissue Prof. Herbert F. West presents the subject of "Comparative Literature" a department unknown at Dartmouthbefore 1919, yet one which followed quite naturally after theperiod of international relations in 1917 and 1918.

COMPARATIVE Literature may be defined as the study of literature in its international relationships. More specifically, perhaps, the study of, and drawing conclusions from, literatures in different languages; how one was influenced by the other, and other fitting and profitable comparisons. Courses in Comparative Literature are a relatively recent phenomenon in the American college. One of the best courses in the heyday of the Harvard triumvirate (William James, Josiah Royce, George Santayana) was Prof. Santayana's course on three philosophical poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe. Prof. W. K. Stewart instituted the department of Comparative Literature at Dartmouth in the year 1919. Most of the major colleges in the country now have such departments.

The courses given at Dartmouth follow the above definition in general but more specifically in the course on "The Romantic Movement" and the course on "Medieval Life and Thought." A sketch of one of these will suffice to explain. The course on "The Romantic Movement" traces the origins and history of Romanticism, in its threefold form—prose, poetry and the drama—in England, France and Germany. The interrelationships and influences of one movement or one man on the other are noted. The lectures include a detailed account of the writers involved, and the student has daily assigned readings in their writings. This is the only course in the department which requires of the student a reading knowledge of either French or German. It is, like the "Medieval Life and Thought," a year course.

The rest of the courses given, six of them, are in general histories of thought of the various countries involved. For example: Comparative Literature 14 is called "Types of German Thought". This may be described and be taken as typical of the others, with one exception, which will be discussed in the next paragraph. Lectures are given on Luther, Erasmus, Grotius, Spinoza, Leibnitz, Herder, Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Kant, Fichte, Hegel, Hebbel, Wagner, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Ibsen. The range of ideas discussed is wide for it includes religion, philosophy, literary criticism, aesthetic theories, international law, the musicdrama, economics, poetry, and drama. Discussions and daily reading assignments in the works of the men named supplement the formal lectures given by the instructor. Spinoza, Grotius, and Ibsen, although not Germans, are Germanic in the broader sense of the word, and are included. Ibsen lived for years in Germany and was considerably influenced by Hebbel. Sometime it is hoped by the writer that a course on Scandinavian thinkers may be included. Similar courses in the department may be listed as follows: Types of American Thought; Types of English Thought; Types of French Thought; Types of Italian Thought. A new course instituted in 1927-28, Types of Rebel Thought, will be discussed separately.

This course has not the national continuity, nor the same time sequence, of the other courses, as it ranges from Socrates in ancient Greece to Romain Rolland in modern France, and includes such diverse thinkers as Lucretius, Jesus, Machiavelli, Bruno, Swift, Cervantes, Swedenborg, Shelley, Heine, Leopardi, Proudhon, Tolstoy, and August Strindberg. The ideas of these men are traced down to contemporary times if vestiges of these ideas remain. In most instances the thought considered radical in its own day has since become part and pattern of our own thinking. Lectures, discussions, and an optional semester thesis comprise the mechanics of the course.

Most of the courses are thus seen to be broad in scope, and because of this, no doubt, lack the profundity of a long concentrated study of one idea or one school of literature or philosophy. As we are concerned with undergraduate study it is hoped that the breadth of these courses gain rather than lose in their possible lack of depth. Somewhere Marcel Proust, the French novelist, has said, "No man can be certain that he has indeed become a wise man ... so far as it is possible for any of us to be wise . . . unless he has passed through all the fatuous or unwholesome incarnations by which that ultimate stage must be preceded. . . . We are not provided with wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves after a journey through the wilderness which no one can take for us, an effort which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world." It is hoped that the student, coming in contact with the ideas of the leading countries of western civilization, reading the stimulating thoughts of the great thinkers of the ages, will so have his perspective broadened, his tolerance strengthened, his mind cleared and tempered, that he may face the often bewildering problems of his own life and times, with the success commensurate with happiness, social well-being, and intelligent citizenship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Associations

December 1928 -

Sports

SportsSport for Sport's Sake, and—for Health

December 1928 By Robert J. Delahanty -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

December 1928 -

Article

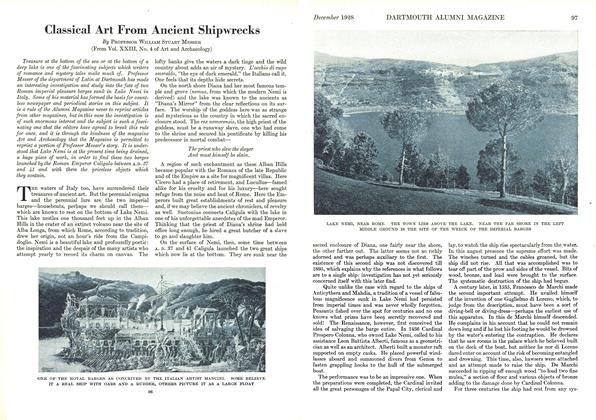

ArticleClassical Art From Ancient Shipwrecks

December 1928 By Professor William Stuart Messer -

Article

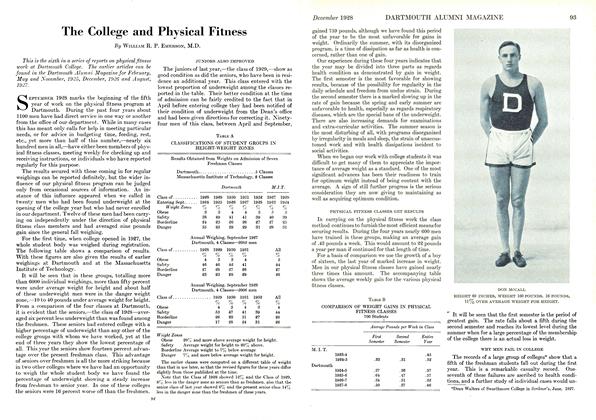

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

December 1928 By William R.P.Emerson, M.D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

December 1928 By Herrick Brown

Article

-

Article

ArticleRESIGNATION OF SECRETARY KNAPP

April 1917 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth-in-Portrait

November 1944 -

Article

ArticleTuck School Perpetuates Their Name

May 1945 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues Welcomes First Woman Lecturer

February 1950 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

SEPTEMBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleThe Frescoes

December 1933 By Albert F. Cochrane