The Closing Year

The college year just closed has been remarkable for many things which suffice to lift it out of the ordinary run and place it among the notable epochs in annals already fairly replete with very white milestones. The completion and dedication of the Baker Library, besides putting the College at last in possession of a thoroughly essential part of its educational plant which was sadly lacking before, produces in the outward aspect of Hanover a change so outstanding as to alter completely the appearance of the College and its familiar campus. To those of us who have longed for this material addition to the facilities of Dartmouth it seems almost too good to be true that it has come to pass—but it actually has, through an act of generosity on the part of Mr. George F. Baker for which every Dartmouth man, undergraduate or alumnus, will be forever grateful. This is what makes it seem so wonderful—the fact that a library, for which it had seemed the College must wait through many years and for which it must strain the resources of its sons, has come to us by free gift and has been erected with what, to those who were not on the spot to see the labor involved, must seem rather like magic.

The library of any college must always be the temple's inner shrine—the abode of the sacred Ark. Books are the very essence of the "educational factory," to borrow a term used by President Lowell in his brief but admirable address at the 150 th anniversary luncheon last spring at Phillips Andover Academy. To have abundant books, worthily housed in conditions which make them readily accessible to the faculty and students who must use them, is a primary essential. Dartmouth now has the space to harbor her needful volumes for many years to come, if not for all time. For that and for sundry other notable gifts, summarized in the president's annual talk at the Alumni dinner at Commencement, every Dartmouth man is devoutly thankful.

And we say "devoutly" with intention, by the way. Is any one of us sufficiently imbued with the feeling that these good gifts and this rapid progress we're so proud of come from an inspiration far above and beyond us ? This is a materialistic age, in which little is said, by comparison with older years, of the bounty of God. The danger is that as prosperity increases and possessions multiply we shall forget what we still owe to faith. The Library is rather a spiritual than a material monument—a Temple of Thought, into which one may properly enter with a lowly, reverent and obedient heart. For this and for all other blessings, may God make us forever thankful.

The Library, however, is not the whole story. It is the great outstanding, visible momument; but there is more behind. By virtue of the Library's existence the College has the facilities at last to proceed to the development of an educational structure far exceeding in scope and possibilities anything Dartmouth has ever known, in the way of an extension of what may be called "honors courses" for the benefit of students endowed with special abilities and a craving to satisfy them. Such a development must necessarily entail a very considerable addition to the costs, involving, as it does, not only a great additional effort in the upkeep of the machinery of the Library, constant additions to the books and' so on, but also the expensive set-up of what one may term the tutorial, or preceptorial, system whereby individuals, or small groups of students, can command extra-special attention.

This the College could not have afforded to undertake at this time had it not been for one other benefaction announced at Commencement; to wit, the gift of $1,500,000 in the form of two investments of $750,000 each—one from the General Education Board funds and the other from a generous individual donor who prefers to remain anonymous for the present. From these combined funds will be derived the necessary income to enable an immediate progress toward an educational system such as few—and those only the largest universities—can hope to offer. Let it be remembered the Dartmouth is not, and has no intention of becoming, a university. It is a college, and a college it intends to remain. But it seems possible now to dream of it as a sort of supercollege, exceeding in opportunity anything that the most sanguine among us could have envisaged.

When, two years ago, President Hopkins outlined before a meeting of the Alumni Council his hopes for the future, he naturally included a Library along with many other things and spoke incidentally of his wish that there might some day be a tower containing a carillon. That the same Council meeting two short years later would find the Library built and in operation, and would hear the soft chime of melodious bells ringing from its steeple, none but a visionary would have dared to predict. But it was even so—and from it one draws the faith to anticipate further miracles of achievement. In this one year, now closed, the College has received in actual benefactions more than it could count as its total assets fifteen years ago.

Nothing succeeds like success. The progress thus far made is due in large part to the readiness of the President and Trustees to be bold in planning and building largely—one might almost say imperially. The Baker Library was designed, not for a half-century, but for the indefinite necessities of all time to come. This boldness has borne fruit and has begotten other benefits. That there was in it nothing Quixotic or chimerical is clear.

Thus does Dartmouth College complete another year of creditable progress, with every augury for continuance of the same through the years that are to come. Fortunate indeed are we, the present alumni, to be alive to see. And doubly fortunate, perhaps, are those of us who knew Dartmouth first in the days of its littleness, for we are the more appreciative of what Dartmouth has become. Yet there must be deep within the heart of such a wholesome humility mingling with the pride. Non nobis, non nobis, Domine!

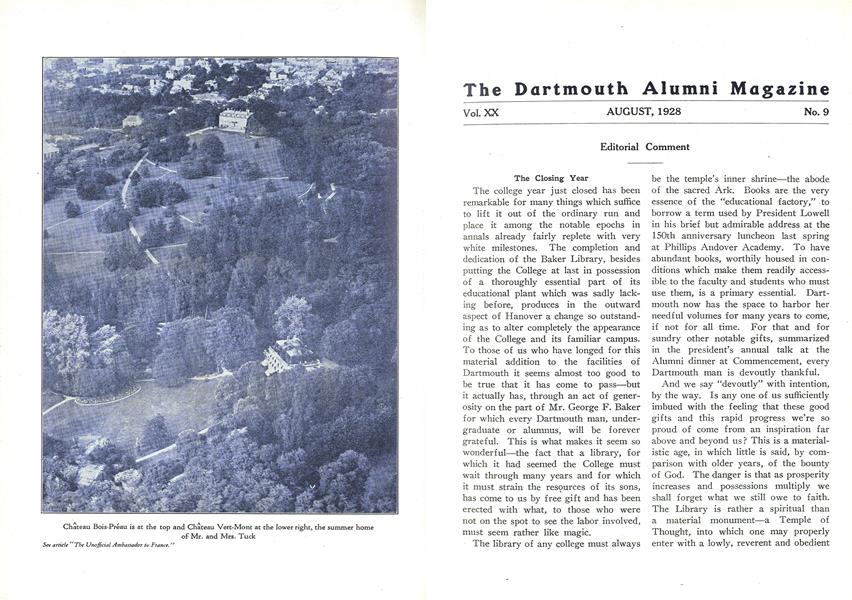

An Unofficial Envoy

There is hardly need to supplement the article printed elsewhere in this issue on the great service of the cause of international amity and good understanding rendered by Mr. Edward Tuck, long resident in Paris, but we would at least direct' the reader's attention especially to that article. We have all known and appreciated the benefactions which Mr. Tuck has sponsored in our own country —especially in our own college—but have naturally not had so intimate a knowledge of his activities in France, where he has spent his business lifetime. These Robert Davis 'O3 considers in detail under the appropriate heading "An Unofficial Ambassador to France" and the account is illuminating.

Dartmouth College has abundant reason to be proud of the service of this notable son, as well as grateful for his many gifts to herself. It is never very easy for an American to make his home abroad and identify himself so thoroughly with the progress of a country not his own, yet at the same time blend therewith an equally active and generous interest in the land of his origin. In doing this Mr. Tuck has succeeded to a marvel, lit is well to have brought home to us, so prone to note only the manifold good things which have been done in our own environment, the fact that this has been by no means a one-sided development but has its counterpart in a generous cooperation overseas.

Its effect on the relationships between the Americans and the French is indirect, but highly important—quite as much so, we imagine, in the long run as are the more direct contacts afforded by officially accredited envoys. Indeed it is often thus. The exploits of Col. Lindbergh as an emissary of goodwill are too recent to require recapitulation. America is judged abroad by what is seen of Americans who come and go—but most of all by those who, like Mr. Tuck, remain as residents through many years and enter into the community life.

An Essential of Teamwork

The Dartmouth alumni at the present time constitute an amazingly effective team. It is doubtful that there is to be found a parallel for them in any other American college, when it comes to a question of intelligent and enthusiastic support for the undertakings of the college administration. To safeguard and insure the continuance of this situation is therefore of paramount importance, because without it there would certainly be a diminution of effectiveness and a dissipation or diffusion of effort which would impede, if it did not prevent, the speedy realization of plans which now appear to be well within the scope of a reasonable ambition.

With this in mind, and seeking to insure against unintentional impairment of alumni resources, the Alumni Council a few years ago adopted a resolution, the purport of which was that, before any considerable or general solicitation of funds from the alumni for college purposes were undertaken, such projects should first be laid before the Council for its official sanction. In consequence at least two such proposals have been referred to the Council and have been sanctioned, while one or two others similarly referred have been postponed. The whole idea, of course, is to prevent collisions of well meant efforts such as might lead to the failure of some desirable plan through mere lack of coordination and direction.

A moment's reflection will suffice to show the necessity of some such provision. The Dartmouth alumni are not overwhelmingly numerous, and there is not to be found among them such a number of men with superabundant means as to afford an inexhaustible field. It would easily be possible, in the absence of any directing agency, to impair the available supply of power to support the needful activity of the College by simultaneous efforts—no matter how well meant or desirable in themselves—to enlist substantial backing for unrelated ends. Particularly would such a situation menace the full effectiveness of the Alumni Fund, on which the College must, for several years to come, depend for the supply of one item in its annual budget.

It may be especially pertinent at this time to bring this matter to the attention of alumni in general because the natural enthusiasms of this triumphal stage in Dartmouth's progress may easily inspire so many laudable ideas involving a recourse to alumni support. To coordinate these as they arise by reference to the judgment of the Alumni Council seems to us to be well nigh imperative if we are to continue in full effect the great supporting power of our alumni as a whole.

That Famous Spirit

In view of the occasional outbursts of smart undergraduate cynicism, which tend to call in question the customs and practices of an elder day, there might seem to be ground for questioning the endurance of some things which have commonly been esteemed rather vital. This is an era in which young men appear to be fearful of over-sentimentality—an era in which it is rather fashionable in some quarters to make light of cherished loyalties, such for example as love of country—in order to dispel any impression that one is a mere member of what is usually called "the herd." At times one is asked to believe that it is a sort of amiable weakness to feel, or at least to give open expression to, a reverence for anything which men commonly hold in reverence—the flag, say, or one's college—as if to confess such sentiments argued one a sort of commonplace Babbitt. It is comforting to feel that this is probably in most cases a pose based on mistaken standards, born of immature judgments and certain to be outgrown; for one could not with equanimity face a future in which Dartmouth men might feel it somehow beneath their dignity to rejoice openly in a fellowship so honorable, or to admit the impulse of a spirit so long cherished.

The student of today is the alumnus of tomorrow. The man who but yesterday was subject to college discipline and in position to see and comment upon the folly of his elders, now becomes an alumnus himself and as such subject in turn to the analysis and criticism of those who follow. It usually happens—and with speed—that such discover there is really something in this Dartmouth Spirit, after all; something real and something vital, without which the College would be a poor thing indeed; something it is not self-belittling to feel and to avow in the sight of men. Argue as one may in one's moments of superior wisdom in favor of having the head rule the heart, it is out of the fulness of the heart the mouth speaketh.

It happens that Dartmouth College is in an especial manner dependent on the enthusiastic spirit of her sons, and it is matter for hearty gratitude that as the alumni body grows in size that spirit grows apace therewith. Only so have we attained to what we now possess; and only by continuing instant in this spirit can we go on—or even hold what we now have. To the thousands who constituted the alumni in 1927 are now added the several hundred eager young men who were the seniors of 1928, but who are seniors no longer. These are welcomed into the great and earnest body of the Dartmouth Alumni with all the "privileges, immunities and signal obligations" appertaining thereto. What the immunities may be is somewhat difficult to put a finger on; but the privileges and the signal obligations all of us know, and all of us can testify that they are worth our having.

The Dartmouth Spirit is one of the realest things in the world. It cannot be seen, in itself, but it can be felt. Its works are manifest. It is the greatest of all the college assets. On it and its maintenance the College was built and has grown. Long may it live!

Why Do They Come?

Does the average student in any college come to that college to get an education, or only to get himself duly graduated? If he comes consciously and sincerely to get an education, as he would go to the nearest tobacconist to get some cigarettes, he may be left quite safely to himself. He will get what he has come for as a matter of adequate self-service. If he has come mainly to get himself duly graduated—which means in its essence nothing more than to avoid being dropped for deficiencies in scholarshipit seems to be a somewhat different matter. The fact that most of our higher institutions of learning insist on a certain amount of prodding and oversight indicates a very meagre belief that the ordinary college man is where he is because of any burning thirst for culture.

Something depends on who is talking. Students today, as did their fathers a generation ago, usually insist that faculties are unduly anxious for their account. Faculties indeed appear to be somewhat less skeptical than they were once—-witness the greater latitude allowed in many colleges to men who have given some evidence of a real purpose and intent to lay hold on what the college is trying to give, the growth of "vagabond" courses and so on—but for the great multitude there remains that mass of irksome disciplinary requirement which indicates that, in the estimation of his elders, the merely average student is not anxious to get his money's worth but is concerned to attain his A. B. degree with the irreducible minimum of work, to which he must be held by stern compulsion lest he fail even of that. Is it an unreasonable assumption? Of course not! If it were, someone outside the undergraduates would discover the fact.

it may not be fair to impute this neglect of opportunities to youth alone. Something very like it, though applied to other ends, appears to endure throughout life, involving other forms of compulsion on the conduct of adults. The student is running true to form. Before you waste too many epithets on him, a little self-analysis may be in order.

Fagging vs. Hazing

Schoolmen from both sides of the Atlantic have been heard of late commenting on one curious difference between the customs of the English "public" schools, so-called, and those of the American private schools and colleges. It has been pointed out that, oddly enough, the "fagging" system of the British schools for boys is derided as intolerable by American critics, who ignore completely the fact that a very similar system of oppressing the lowerclassmen obtains in pretty nearly every American college, although it is frowned upon as an intolerable institution when applied to secondary schools abroad involving much younger boys.

The extent to which the college freshman is held liable by upper-classmen to run errands, collect mail, beat rugs and do other services varies with the institutions in question, no doubt, but to an older alumnus it does seem as if the custom had grown greatly with the years. It seems to be regarded as wholly fitting and proper that new-comers should "fag" for those longer in residence, just as is the case with the little boys in the British schools, although with us the fags are several years older and must experlence some bitterness of spirit at finding themselves, lately seniors in a big prep school, relegated to the role of servants in a college dormitory.

The intent of this comment is not necessarily to declaim against the system, which is at least better than the organized hazing which it appears (at least in a measure) to have supplanted and which may have the effect of curbing the natural freshness of the newcomers, long recognized as an evil which demands stern remedy. Rather is the intent to draw attention to the curious parallel with the customs of the English lower schools and to hint at a lack of consistency on the part of such as talk as if the custom in England were tyrannical beyond what a free-born American would tolerate. It may be pretty much of a muchness all around, and it all arises in any case out of the widely diffused feeling that by some means or other the newest comers have to be taught their place and kept in it. That idea is as old as the hills, and since it is so persistent it may actually have validity. Happy the institution where this ineradicable propensity manifests itself in the least harmful and violent of ways.

Are They Irreligious?

A visitor from Mars, supposing one could come down to us, might be a trifle amused by the exaggerated concern which terrestrial critics are manifesting for the religious estate of the young men and women in the colleges. It might seem odd to him that the young men and women in the colleges should be so generally assumed to be essentially different from young men and women outside—or different from much older men

and women—in this particular. It seems to us that they are not, really; but from the outgivings of the magazine writers and occasional educators it is usually made to appear that in their attitude toward formal religion the college students of the day present a problem highly peculiar.

Is' it not somewhat more reasonable to suppose that the undergraduates of the American colleges are very much like other people elsewhere? There has certainly been a fairly general complaint during recent years that public indifference toward the churches is growing and consequently there has been a demand that something be done about it. It isn't especially remarkable if this tendency has manifested itself among the younger people of the country who happen to be studying in the colleges. For a guess, the American college population of the moment, which we may estimate as including about half a million youngpersons, is very much like the non-college population in its attitude toward things of the spirit when judged by the standards which for several generations were accepted as determining whether or not an individual could be called "religious." It is even matter for doubt whether those now in college are in fact any less religiously disposed than were their fathers; but as they are infinitely more numerous it is natural their demonstrations should be more impressive.

Something may be at fault with the standards, as applied to the present day. President Hopkins recently wrote in a letter to a critical alumnus, "llf being religious necessarily means to be churchgoing, or if being good means being standardized to the conventions of a few years ago . . . then Dartmouth is none of these things." The same can be said of pretty nearly every college that is worth its salt. But one is glad to append the belief that being religious does not necessarily mean mere formal observance, or mere lip-service; and one is particularly glad to add thereto a belief that the youth of the present day, especially in the American schools and colleges, is just as genuinely religious in spirit as the youth of any previous, day. It isn't spelled out in the same characters, to be sure, but that ought not to lead to any mistake of fact as to what is really there. The cleanness, the loyalty, the reverence for right living and fair play, the capacity for ready self-sacrifice on behalf of such ideals as youth does honestly and candidly recognize—all these things are indicative of a spirituality which it would be well to admit savors of something higher than the purely animal.

Consider the attitude of the younger men toward each other in matters which are peculiarly their own concern. President Coolidge mentioned this in his address at the Phillips Andover sesquicentennial last May, stressing the highly exacting standards on which youth inexorably insists. Has there ever been a time in which morality, properly so called, has been held in more exigent esteem among college men? Has there ever been cleaner living? Ought quite so much to be read into the mere decline of daily chapel services, as if on that alone depended the religiosity of the day? One suspects that college students are at bottom quite as truly religious as they ever were—hopefully indeed are somewhat more so than of yore—but that neither they nor their critics recognize the fact for what it is. It might be well if the essentially religious quality of the student mind could be drawn to the notice alike of those who have it, and of those who persist that it isn't there merely because it doesn't lead to the same set of outward manifestations that used to be expected.

Speaking generally, it may be said that mankind in the mass is not quite so self-confident as it used to be in the assumption that it knows all about God and can set metes and bounds to true religion to which every one must conform. That the young men in college reject any more than we others do of the ancient tests of religiosity seems too much to believe. What they reject it is wholly probable that you also reject. Why pretend otherwise, as if all virtue lay in formulae, and no virtue in anything else ? The orthodoxy of today was heresy forty years ago. President Tucker, while a professor of theology at Andover, was tried for his spiritual life, along with four other highly reputable and godly men, for holding that God was probably too good and too just to condemn to everlasting punishment heathen to whom the gospel happened not to have been preached! It is always a risky business, this dogmatizing about the aims and purposes of the Creator. Men have been changing their ideas about it ever since the dawn of civilization, and curiously enough the changes haven't yet wrecked religion. May it not be in order to assume that God can still handle the case among his creatures ?

These young men and women obviously do not see religion exactly as it used to be seen, of course; but we doubt that they reject God, or fail in their willingness to be of service to man under the inspiration and leadership of Jesus Christ. That they refuse to exalt formal worship may be true, but we doubt that they differ very much from their contemporaries in that. In any event we have a lurking suspicion that the will of Heaven is not going to be thwarted by what looks like the careless indifference of juniors and sophomores, who are at bottom a great deal more religious than they know themselves. There is even a possibility that they are more religious than are some of their critics.

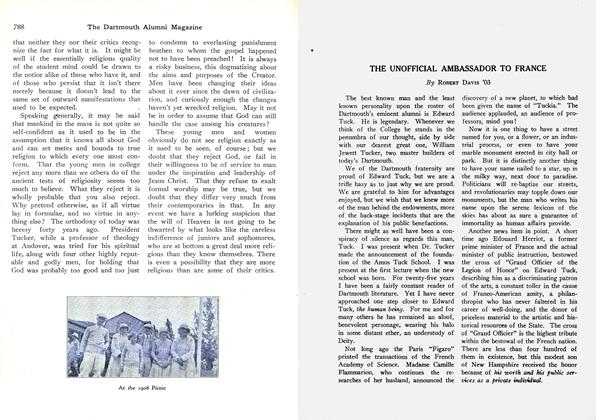

Château Bois-Préau is at the top and Château Vert-Mont at the lower right, the summer home of Mr. and Mrs. Tuck

At the 1908 Picnic

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNOFFICIAL AMBASSADOR TO FRANCE

August 1928 By Robert Davis '03 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF ALUMNI COUNCIL

August 1928 -

Books

BooksGREEK THOUGHT IN THE NEW TESTAMENT.

August 1928 By Charles D. Adams -

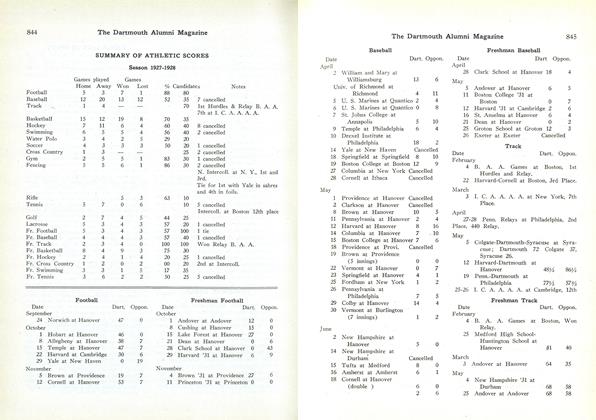

Sports

SportsSUMMARY OF ATHLETIC SCORES

August 1928 -

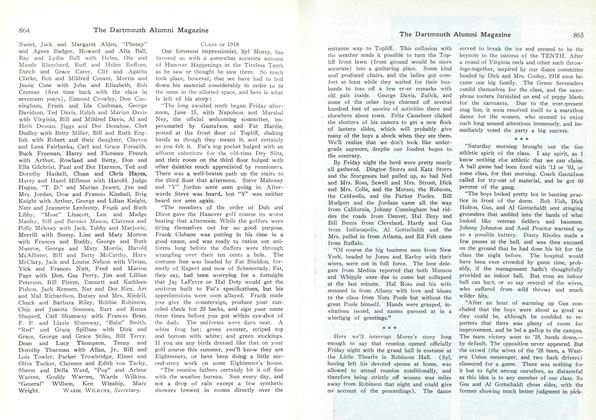

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

August 1928 -

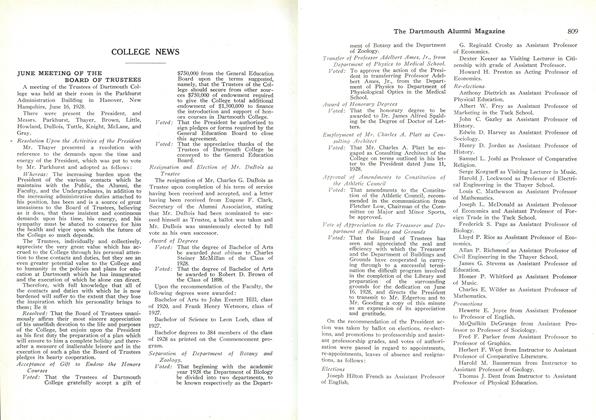

Article

ArticleJUNE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

August 1928