The New York Times commented editorially on President Hopkins' opening address, reprinted in full in this issue of the MAGAZINE, under the caption, "Orientation":

It is doubtful if a better definition of the objective of a liberal college has been made than that which President Hopkins of Dartmouth framed in his address at the opening of the 161 st year of that once "little college," now loved by a number exceedingly large, and sought by so many that, as a sophomore complained, it has become "too independent." After differentiating this American institution from the technical school, and the "truncated" junior college from the undergraduate departments of universities, he describes this type of college as interested, by contrast, in all human thinking rather than the development of ideas in a specific field. From this general survey,, of higher education the definition emerges, with some sense of orientation in time rather than in space:

The objective of the liberal college is to stimulate minds to activity in consideration of present-day problems under restraint of lessons of the past and under spur of imagination as to the possibilities of the future.

There is no place in it for a mind that is not active in all three tenses. The mind that interests itself merely in the past, that depends entirely upon the written word, produces the bookish man. The mind which looks to the future alone, knowing naught of the past, may find one idea of worth, but at the hazard of a "thousand avoidable mistakes":

An individual or a generation which ignores its continuity with the past is incapable of understanding its relation to the present and renders itself sterile for participating in the future.

It is in the habit of courageous response to contemporary life that these relationships to the past and future furnish leadership in the present. The youth of America least of all should let their enthusiasm be dulled or their aspirations circumscribed with such a world before them. Education is not merely an orientation that adjusts one to environment; it involves struggle to conquer. If youth abandons the buoyant attitude toward the present and strikes the pose of passivity, which is a phase of pessimism, it slips into the absurdity that follows artificiality. It is in the spirit of the times or in the attitudes taken by groups or generations that the difference lies, since natural attainments and mental capacities cannot vary so greatly as to account for the differing achievement.

"The single flight of a fearless youth" has done more to promote good will than "provincial legislatures can destroy." There suddenly comes now and then a rehabilitation of the spirit of mankind in the presence of a courageous response to the challenge of environment—one that makes us know that "dour rationalization" is not all. If such an address could be heard by all the college youth in America, it should stir them to see themselves as pioneers in a new age and oriented in time instead of mere space.

The following editorial appeared in the Boston Herald on September 20. 1929:

"It is the misfortune of Boston that Mr. Ernest M. Hopkins does not live and work here and give the community the benefit of his outlook on life. Few men among our educators have sifted the false and the true of a bewildering age more skilfully than he, and perhaps no college president of the day has been so successful in holding the esteem of the older generation, and the respect and affection of the up-and-coming.

"President Eliot used to tell a story of hearing himself referred to as 'old man Eliot' in a horse car when he was under forty, and as 'Charlie' in a trolley car when he was more than 80. He was mature when he was young, and young when he was mature. There is a rough resemblance between him and the Dartmouth president. Mr. Hopkins came to intellectual maturity years before other men of his age, and 'President Hopkins' was the colloquial designation at Hanover during his novitiate. He is now 'Hoppy' to undergraduates and alumni, and it is not the familiarity of casual regard which has so labelled him. It is a tribute to his refusal to abide blindly by conventions which do not properly apply to the present. Reading the address which he delivered at Dartmouth last night, even a non-Hanover- ian can understand why he holds his unique place. Like President Eliot and Father Wil- liam, he has kept all his limbs very supple.

" 'Optimism and buoyancy are qualities which are natural attributes of youth,' said Mr. Hopkins. 'When youth abandons these, it abandons the vital sources of power to make itself an active factor rather than a passive one in the life of its generation.' Speaking on Orientation—did the freshmen anticipate a disquisition on the Far East?—he reminded his hearers that there is a helpful past and a promising future, that our main problems are of the present, and that college youths should be alert to the spirit of the day. They should be serious without solemnity, determined without losing their sense of humor, profound without becoming dull, and purposeful while still remaining good-natured. 'Poignancy is not a necessary concomitant of intelligent concern . . . dour rationalization is not all of life.' A few evangelical Hallelujahs and the 'let's go' mood may be helpful. 'The world at large desires to know truth,' and President Hopkins asks college graduates to spread it. 'Most great achievement springs from human minds which acquired the habit of courageous response to the challenge of contemporary life.' In short, he asked his young charges to keep their limbs very supple.

"What is the aim of Dartmouth? Certainly the primary purpose is not to satisfy the transitory, nebulous sentiments of fickle undergraduates. A liberal college should teach what is best for mankind as a whole. It should not 'ignore vital phases of human existence.' It should stimulate minds to work 'under restraint of lessons of the past and under the spur of imagination as to the possibilities of the future.' The principal concern of the liberal colleges, of which Dartmouth is a notable member, is 'that civilization shall benefit from the absorption into itself of individuals who are better, wiser and more competent and more co-operative than they would otherwise have been.'

"That old phrase of Daniel Webster's which moved him and his hearers profoundly is still a good sentence, but not in accord with the facts of today. There are those who love Dartmouth, but it is no longer 'a small college.' As President Hopkins says, the material, relevant facts are 'not as vital as the intangibles beyond them,' but they are most impressive. Last year, 5,683 alumni contributed to the support of their Alma Mater. It cost $1,633,000 to pay for what the students received, and it cost them only $809,000 or less than half the expense of what they got.

"We hope that the president's associates will put this significant address into pamphlet or book form and distribute it widely. It would make excellent reading for the parents of every boy at Dartmouth, and every graduate of the institution."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

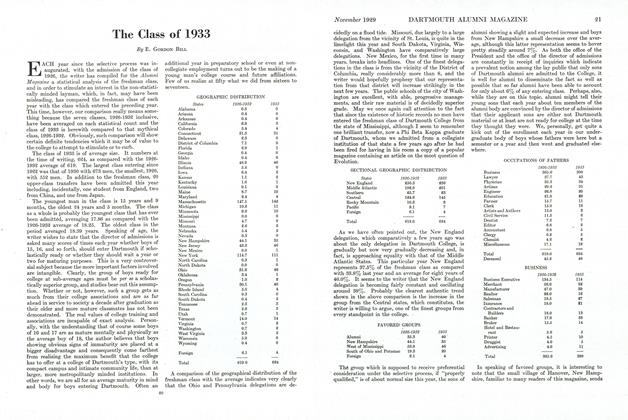

ArticleThe Class of 1933

November 1929 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

Article"ORIENTATION:" The Opening Address of Dartmouth's 161st Year

November 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1929 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

November 1929 By Frederick W. Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

November 1929 By Robert J. Holmes

Article

-

Article

ArticleWho's Who in Hanover

March 1933 -

Article

ArticleAttains Flag Rank

February 1947 -

Article

ArticleCampus Communications Leaders.

MARCH 1966 -

Article

ArticleWhat the Workshops Meant

JUNE 1970 By GUY DE MALLAC-SAUZIER -

Article

ArticleGREEN JOTTINGS

JULY 1969 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleORIGINALS AND COPIES

JUNE 1991 By James O. Freedman