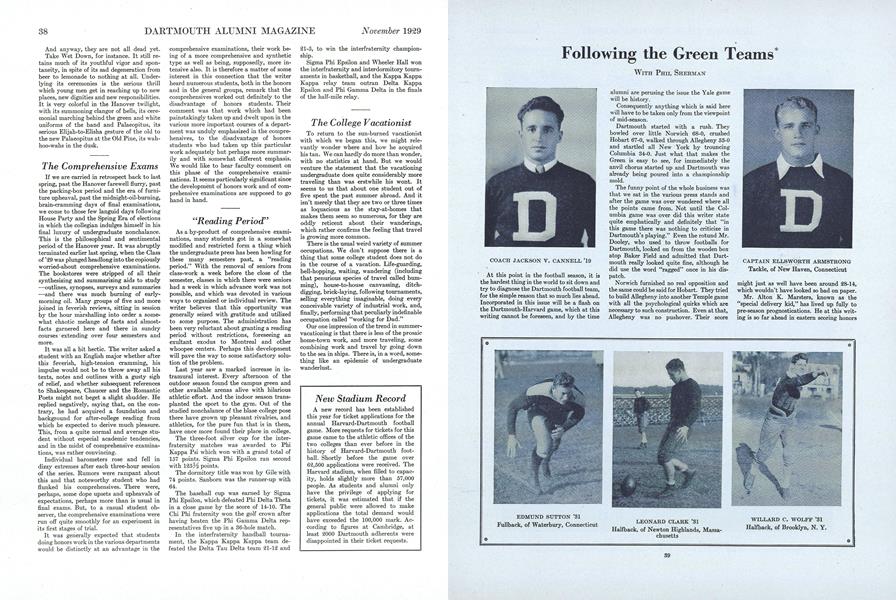

If we are carried in retrospect back to last spring, past the Hanover farewell flurry, past the packing-box period and the era of furniture upheaval, past the midnight-oil-burning, brain-cramming days of final examinations, we come to those few languid days following House Party and the Spring Era of elections in which the collegian indulges himself in his final luxury of undergraduate nonchalance. This is the philosophical and sentimental period of the Hanover year. It was abruptly terminated earlier last spring, when the Class of '29 was plunged headlong into the copiously worried-about comprehensive examinations. The bookstores were stripped of all their synthesizing and summarizing aids to study —outlines, synopses, surveys and summaries —and there was much burning of earlymorning oil. Many groups of five and more joined in feverish reviews, sitting in session by the hour marshalling into order a somewhat chaotic melange of facts and almostfacts garnered here and there in sundry courses 1 extending over four semesters and more.

It was all a bit hectic. The writer asked a student with an English major whether after this feverish, high-tension cramming, his impulse would not be to throw away all his texts, notes and outlines with a gusty sigh of relief, and whether subsequent references to Shakespeare, Chaucer and the Romantic Poets might not beget a slight shudder. He replied negatively, saying that, on the contrary, he had acquired a foundation and background for after-college reading from which he expected to derive much pleasure. This, from a quite normal and average student without especial academic tendencies, and in the midst of comprehensive examinations, was rather convincing.

Individual barometers rose and fell in dizzy extremes after each three-hour session of the series. Rumors were rampant about this and that noteworthy student who had flunked his comprehensives. There were, perhaps, some dope upsets and upheavals of expectations, perhaps more than is usual in final exams. But, to a casual student observer, the comprehensive examinations were run off quite smoothly for an experiment in its first stages of trial.

It was generally expected that students doing honors work in the various departments would be distinctly at an advantage in the comprehensive examinations, their work being of a more comprehensive and synthetic type as well as being, supposedly, more intensive also. It is therefore a matter of some interest in this connection that the writer heard numerous students, both in the honors and in the general groups, remark that the comprehensives worked out definitely to the disadvantage of honors students. Their comment was that work which had been painstakingly taken up and dwelt upon in the various more important courses of a department was unduly emphasized in the comprehensives, to the disadvantage of honors students who had taken up this particular work adequately but perhaps more summarily and with somewhat different emphasis. We would like to hear faculty comment on this phase of the comprehensive examinations. It seems particularly significant since the development of honors work and of comprehensive examinations are supposed to go hand in hand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

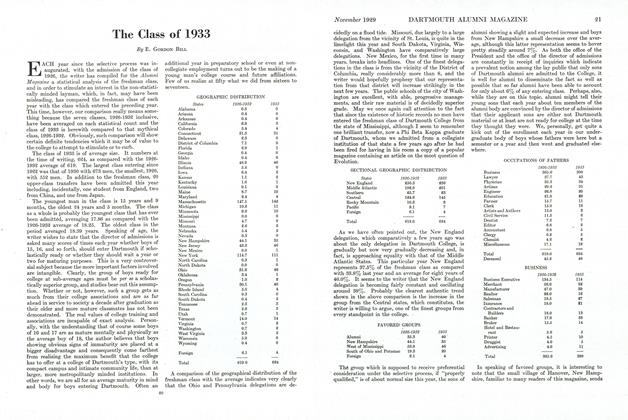

ArticleThe Class of 1933

November 1929 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

Article"ORIENTATION:" The Opening Address of Dartmouth's 161st Year

November 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1929 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1929 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

November 1929 By Frederick W. Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1909

November 1929 By Robert J. Holmes

Albert I. Dickerson

-

Article

ArticleLectures

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

JANUARY 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

FEBRUARY 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

October 1937 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

May 1938 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

January 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON