The Department of German

Professor R. W. Jones carries on the story of the curriculum in this number with an account of the German department. There is an added interest to this article when onerealizes that German departments in American collegeshave been almost reconstructed since the war when therewas a general abandoning of the study of that language. Inthe next number the department of Latin will be discussed.

THE courses in the German department are planned to suit the needs of two classes of students, those who wish to acquire a reading knowledge of the language as quickly as possible so that they can use German as a tool in pursuing advanced studies, and those who wish to obtain a knowledge of the German language and literature and of the culture and thought of Germany for its own sake.

The number of those in the first group has increased relatively since the war because the study of German was abandoned to such an extent in the secondary schools. When a student decides upon his life-work and begins to look up the requirements of the graduate and professional schools, he finds that a knowledge of German is usually demanded. For many lines of work, indeed, it is almost indispensable. The importance of German for the study of chemistry, for instance, is indicated by a recent tabulation of the references in a volume of The Journal of the American Chemical Society, which shows that of the foreign periodicals (i.e., excluding those published in the United States) 52.5% were published in the German language.

What may be termed a fairly satisfactory reading knowledge can be obtained by taking courses 1-2, 3-4, and 13-14. After the first semester the chief emphasis is laid upon the reading, the material selected consisting mostly of modern stories and plays. In German 13 and 14 some reading of a scientific nature is chosen. There does not seem to be sufficient demand to warrant putting in a special course in scientific German. Experience shows, moreover, that a student who can read fairly difficult prose of a general character will have little trouble in mastering the difficulties of a special technical vocabulary.

Students whose interests are primarily linguistic may take the course in composition and conversation; those who would prefer to make the acquaintance of the classical writers Schiller and Lessing may choose German 15-16 instead of courses 13-14 in which the works of more modern prose writers are read.

For these elementary courses, including the freshman courses for those who enter with two or three years of German, the publishing houses, which as a result of the war hesitated to put out new books, are now making available a constantly increasing number of works of very modern writers, to meet the demand incident to the revival of interest in German throughout the country.

VALUE OF ADVANCED COURSES

The advanced courses in German introduce the student more systematically to the wealth of one of the great literatures of the world. A full year course is devoted to Goethe, the greatest of all German poets by reason of the depth of his personality and the wide range of his interests and accomplishments. Especially his masterpiece Faust, which has been termed a world tragedy of the human spirit, and his matchless lyric poems are deserving of study and can not be fully appreciated unless read in the original.

Aside from lyric poetry it is in the field of the drama that German literature has reached its greatest heights, and for that reason three semester courses are given over to this subject. In the first two semesters special emphasis is laid upon the historical development of the German drama during the classical period of the eighteenth century; in the third semester the works of later writers are studied, including Kleist, who was fired by the new patriotic spirit that was awakening in Germany at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Grillparzer, Austria's foremost dramatist, and Hebbel, who laid the foundation of the modern psychological and social drama in Germany.

In a one-semester course the student follows the development of prose fiction from the Romantic movement of the beginning of the nineteenth century, through the works of the so-called Young German group, writers inspired by political and social strivings and ideals, to the more realistic productions, the stories of peasant life, and, particularly, the works of those great masters of the novelle, Keller and Meyer.

The work of the separate courses is correlated and supplemented by a year course covering the whole field of German literature from the early beginnings down to recent times.

The greatest handicap with which students interested in German have to contend is the still relatively small amount of German offered in the preparatory schools. They are obliged to take in college elementary work which they could have done more easily and profitably at a younger age. But the situation is slowly improving, though it will take years to repair the undoubted mistake of dropping German from the curriculum of the schools. Germany is again getting on its feet economically, and along with the economic recovery there is coming the realization that Germany has intellectual values to offer the world which must not be neglected.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

February 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Round Table

February 1929 By Leonard W. Doob '29 -

Article

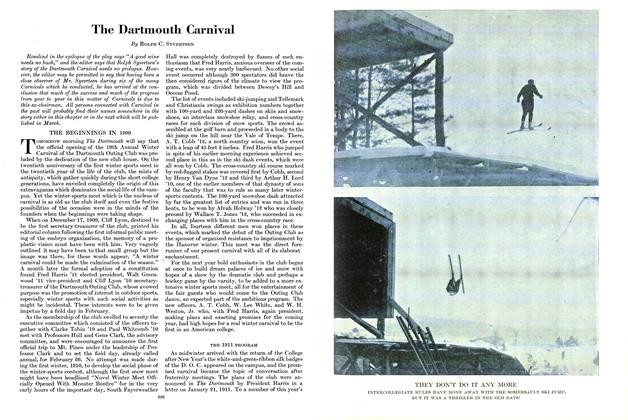

ArticleThe Dartmouth Carnival

February 1929 By Rolph C. Syvertsen -

Article

ArticleAn Umpire Talks!

February 1929 By Albert D. (Dolly) Stark -

Article

ArticleThe Story of an Indian

February 1929 By Samson Occom -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1923

February 1929 By Truman T. Metzel