That's what E. M. Forster wrote at the beginning of his novel Howards End some 75 years ago. So I will. Samuel Fowler Dick- inson '95 (that's 1795), a founder of Amherst College, had a granddaughter who could write. I mean write. She couldn't spell real well and her punctuation was a disaster, but she wrote poetry and prose like no one before or since. Her name was Emily Elizabeth Dickinson and 100 years ago this month, she died, virtually unknown, in her hometown of Amherst, Mass.

At her simple funeral, a few mourners saw the body at the Homestead, the house she lived in most of her life, her lifeless form bedecked in the white cloth that had become the hallmark of her eccentricity. Draped about her neck were her favorite blue violets, and when she was borne to the family plot, it was not through the public roads of Amherst, but, as she had directed, out the back door to the cemetery three short fields away. Along with family, friends, and the minister was Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a well-known man of letters.

For us today, there is rich irony in this scene, because Higginson, as one who might well have thrust Emily Dickinson into literary prominence - he was after all a regular contributor to the prestigious Atlantic Monthly and had received poems from Emily over a period of more than 25 years - utterly failed to recognize her poetic genius. She was too unconventional for him; the end rhymes (when they existed at all) were imperfect, out-of-tune. Worse yet, her grammar was faulty - a tragic flaw from the Boston Brahmin point of view.

It was not until Higginson was involved with the actual editing of her poems, some three years after Emily's death, that he began to appreciate her poetry. And even then, his deep conservatism caused him to alter offending lines, add maudlin titles - in short, to reduce many of the startling originalities of her verse to the dictates of popular taste.

Today, we know a great deal about the diminutive woman who imagined herself maturing into "the belle of Amherst," though there still remain questions that haunt biographers, scholars, and others alike: Who was the man in her life? Was there more than one? Was there a woman, too, who was the real object of her love? Wasn't she neurotic because of an overly-domineering father? And why in those last years did she become progressively reclusive, finally seeing no one outside her immediate family?

The rough outlines of Emily Dickinson's life are well-documented and clear: From a very normal childhood in Amherst and a year at nearby Mt. Holyoke Seminary, Emily returned to the Homestead where, following brief visits to Philadelphia, Washington and Boston, she spent the rest of her life.

Yet as much as we can determine from a vast array of secondary sources, we may never know more about Emily's inner life than what she herself revealed in those haunting, cryptic poems she left locked in a wooden chest in her bedroom, and in those wonderful letters many of her correspondents saved. For when she died, her sister Lavinia burned all of Emily's personal manuscripts except - the poems.

Had Vinnie tossed in the poems with the other papers she destroyed, Emily Dickinson would surely be known to only a handful of 19th-century scholars in American literature, if at all. Fortunately, this was not the case. Vinnie, astonished to find hundreds and hundreds of poems sewn together by Emily into some 49 packets, became convinced, even obsessed, with the notion that her sister's poetry should be published.

Unable, and perhaps unwilling, to entrust publication to Susan Gilbert Dickinson, their older brother Austin's intelligent but sullen wife, Vinnie turned to Mabel Loomis Todd for help. Todd, an accomplished artist actress-author who had taken Amherst society by storm after her arrival from Washington in the summer of 1881, resisted at first. But at Vinnie's repeated behest, she agreed to edit the poems, seeking the assistance of Higginson, who accepted on the condition that Todd do the bulk of the work.

When the first edition of Emily Dickinson's poems appeared in November 1890, it was a smashing success that saw two reprintings by January and 11 editions over the next two years. A second and third series followed fast and then there was trouble. During the editing process - and for some five or six years preceeding - Mabel had been carrying on a turbulent love affair with the one man who was in many ways closest to Emily Dickinson, her brother Austin. But that, as they say, is another story (a story, incidentally, I am writing when I leave the College).

In the meantime, gentle reader, if you feel like "connecting" yourself, get over to your local version of Baker Library and check out the Harvard Belknap Press editions of Miss Emily's Letters and Poems (3 vols. each). You may well discover - or rediscover - the extraordinary power of one who made connections of the most profound order: one who could write, "If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

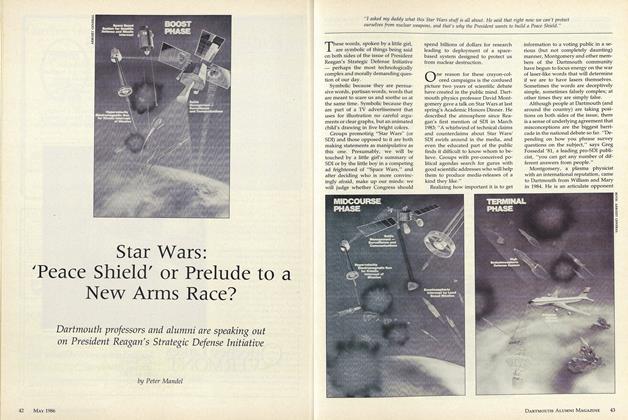

FeatureStar Wars: 'Peace Shield' or Prelude to a New Arms Race?

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Feature

FeatureNative Americans at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Peter Mandel -

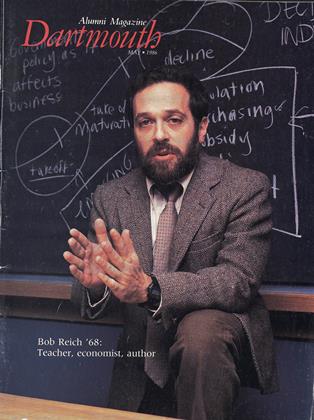

Cover Story

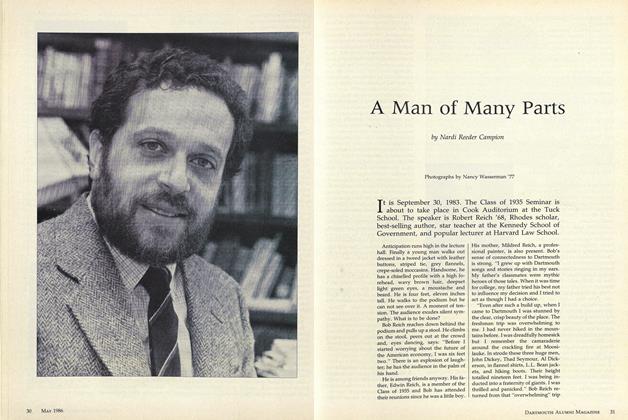

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

May 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Article

ArticleBack where it all began: Al McGuire at Dartmouth

May 1986 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

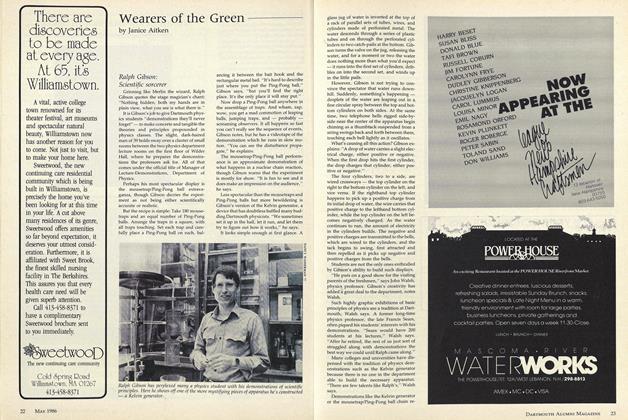

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

May 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

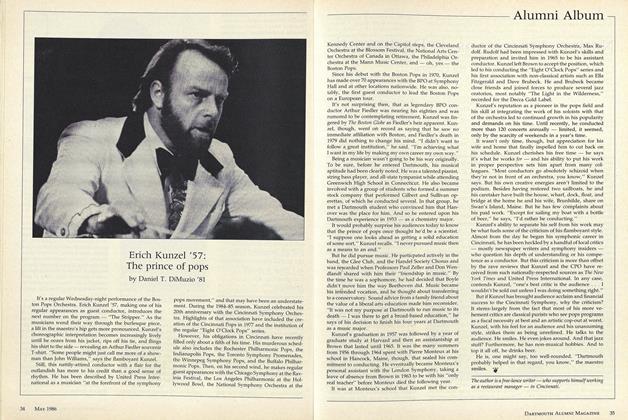

ArticleErich Kunzel '57: The prince of pops

May 1986 By Daniel T. DiMuzio '81

Douglas Greenwood

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor75 and Counting

OCTOBER, 1908 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Real World

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorSome Thoughts on Commencement, 1985

June • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Place of Art

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

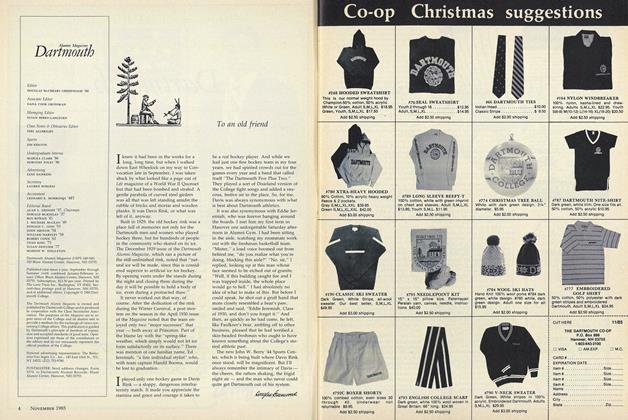

Lettter from the EditorTo an old friend

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

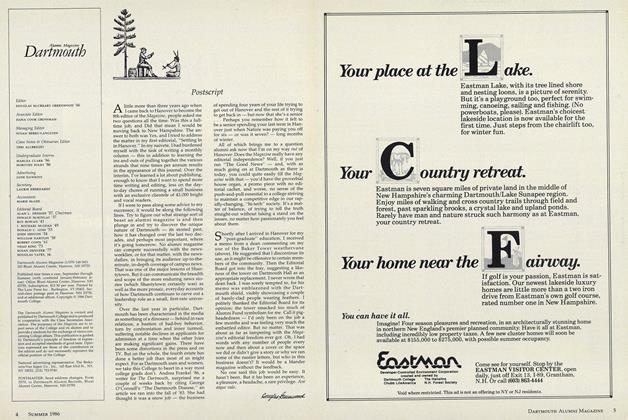

Lettter from the EditorPostscript

JUNE • 1986 By Douglas Greenwood

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

MARCH, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorBetween the Lines

DECEMBER 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorContinuing Education

APRIL • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Family Affair

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

MAY 1932 By Louis P. Benezet