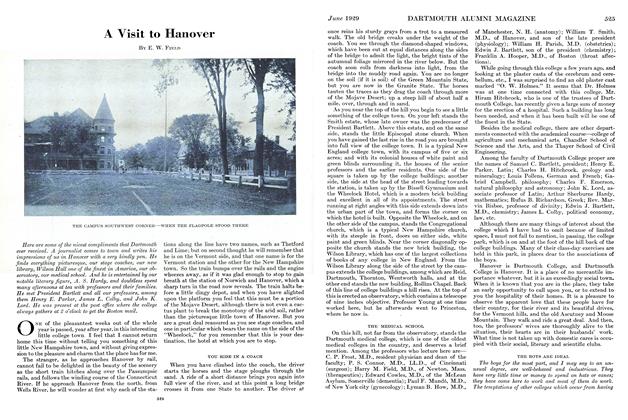

It is strange, this aspect of cloistered serenity, this atmosphere of academic dignity, which the visitor from the "outside world" sees and feels when walking under the elms of a college campus. The spirit of wise old men seems to be in the air, and a quiet veneration for learning, and that sort of cumulative soul of the college which grows as generation upon generation of its sons go out into the world taking a part of the college with them and leaving a part of themselves. All this seems quite tangible and almost inescapable to the stranger walking the green lights and shadows of campus turfs. Yet the student, following unreflectively the loose routine of his day, is altogether unconscious of it all. And if it were brought to his attention, he would probably accuse one of frequenting the cinema and reading CollegeHumor. It is rather odd.

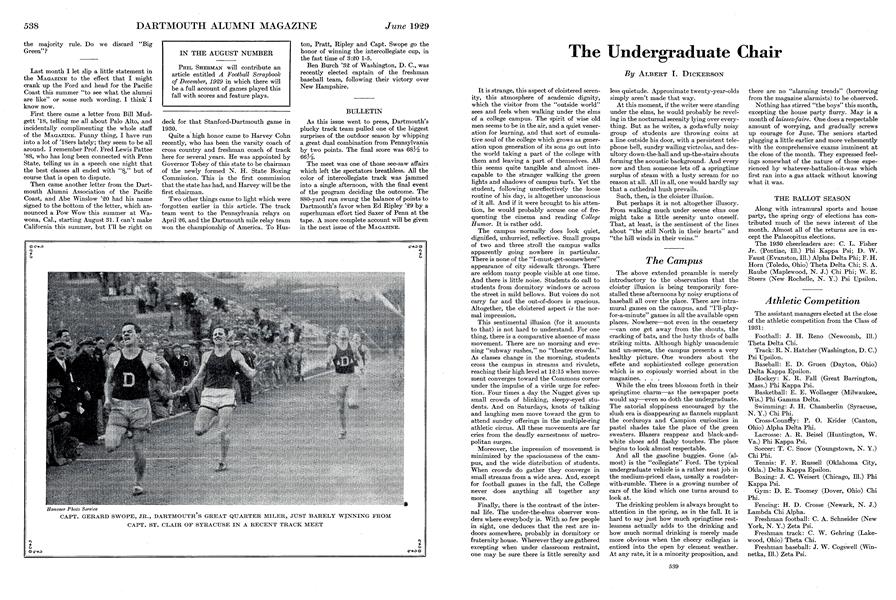

The campus normally does look quiet, dignified, unhurried, reflective. Small groups of two and three stroll the campus walks apparently going nowhere in particular. There is none of the "I-must-get-somewhere" appearance of city sidewalk throngs. There are seldom many people visible at one time. And there is little noise. Students do call to students from dormitory windows or across the street in mild bellows. But voices do not carry far and the out-of-doors is spacious. Altogether, the cloistered aspect is the normal impression.

This sentimental illusion (for it amounts to that) is not hard to understand. For one thing, there is a comparative absence of mass movement. There are no morning and evening "subway rushes," no "theatre crowds." As classes change in the morning, students cross the campus in streams and rivulets, reaching their high level at 12:15 when movement converges toward the Commons corner under the impulse of a virile urge for refection. Four times a day the Nugget gives up small crowds of blinking, sleepy-eyed students. And on Saturdays, knots of talking and laughing men move toward the gym to attend sundry offerings in the multiple-ring athletic circus. All these movements are far cries from the deadly earnestness of metropolitan surges.

Moreover, the impression of movement is minimized by the spaciousness of the campus, and the wide distribution of students. When crowds do gather they converge in small streams from a wide area. And, except for football games in the fall, the College never does anything all together any more.

Finally, there is the contrast of the internal life. The under-the-elms observer wonders where everybody is. With so few people in sight, one deduces that the rest are indoors somewhere, probably in dormitory or fraternity house. Wherever they are gathered excepting when under classroom restraint, one may be sure there is little serenity and less quietude. Approximate twenty-year-olds simply aren't made that way.

At this moment, if the writer were standing under the elms, he would probably be reveling in the nocturnal serenity lying over everything. But as he writes, a godawfully noisy group of students are throwing coins at a line outside his door, with a persistent telephone bell, sundry wailing victrolas, and desultory down-the-hall and up-the-stairs shouts forming the acoustic background. And every now and then someone lets off a springtime surplus of steam with a lusty scream for no reason at all. All in all, one would hardly say that a cathedral hush prevails.

Such, then, is the cloister illusion. But perhaps it is not altogether illusory. From walking much under serene elms one might take a little serenity unto oneself. That, at least, is the sentiment of the lines about "the still North in their hearts" and "the hill winds in their veins."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Faces in the Windows

June 1929 By Clifford Hayes Smith '79 -

Article

ArticleAviation Opportunities for Dartmouth Men

June 1929 By Lieut.Barrett Studley,U.S.Navy -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1923

June 1929 By Truman T.Metzel -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1929 -

Article

ArticleA Visit to Hanover

June 1929 By E.W.Field -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1898

June 1929 By H.Philip Patey

Albert I. Dickerson

-

Article

ArticleGreen Key

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleBait and Bullet

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleIn the Tower Room

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

January 1935 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1936 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

October 1938 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON