Nevertheless, in emphasizing the college function to develop a habit of mind, we cannot generalize that the college should disregard what for the time being seems to be factual knowledge or that it should give release to its students from the obligation to acquire due measure of this. A learning which has no background and no method will little deserve the name of learning. If we do not know how men have thought in the past or do not know the processes and the tests by which certain beliefs have come to be held as axiomatic truths, we are little likely to find that our habits of mind either have utility or that they afford any basis for self-satisfaction. Moreover, it seems to be true that the law of unearned increment applies to the human mind, as elsewhere, and that the greater knowledge a man possesses, the easier it is for him to acquire more. The mind, disciplined by experience in careful analysis of what is held to be fact and trained to acquisitive power by securing possession of existent knowledge, reaches out more surely with its arms of speculation and imagination toward new truth and grasps this more securely when touched than does any other.

The question will doubtless be asked at this point which is constantly asked by critics of the American college. Why, if these things are so, does the college allow time to be spent on anything except mental development? Why are extraneous things, such as physical training or the development of recreational aptitudes made a part of college requirements? Why are the distractions of elaborate social events allowed to intrude upon the time of the college year? Why are the emotional fervors of intercollegiate athletic competition tolerated? I will not attempt here to discuss the extent to which these are legitimate. However, the argument is not conclusive that their very existence must of necessity call for apology.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

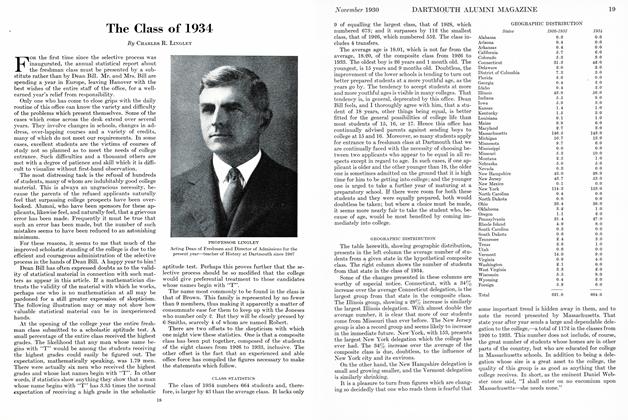

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

November 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1913

November 1930 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1920

November 1930 By Allan M. Cate -

Article

ArticleA Course in the Department of Biography

November 1930 By Harold E. B. Speight

President Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate and His College

November 1928 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleAN ACADEMIC HUNDRED THOUSAND

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleOLD CULTURE AND NEW

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleWIDENED BOUNDARIES

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleEMPHASIS ON CONSTRUCTIVE THOUGHT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleVALEDICTION

April 1934 By President Hopkins

Article

-

Article

ArticleCHINNING RULES

October, 1909 -

Article

ArticleTHAYER SCHOOL BANQUET AT MOOSE MOUNTAIN CABIN

April, 1922 -

Article

ArticleTuck's Executive Program

October 1973 -

Article

ArticleAUSTRAL AND AMADIO

MARCH 1931 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS DENIES DISCRIMINATION AGAINST JEWS

June, 1926 By Ernest M. Hopkins -

Article

ArticleGeorgia

JUNE 1969 By GLOWER W. JONES '58