For a long time I have speculated upon the circumstance that while the origins and the development of such institutions of society as the church, the state, and the home have been and are being subjected to the critical analysis of microscopic examination, the interpretations and speculations of what constituted real culture have been nowhere scrutinized in any like detail.

Professor Charles A. Beard, the qualities of whose own culture and cosmopolitanism alike are beyond question, has suggested in his writings more than once in recent years that the ideals of culture were originally defined by the landed aristocracy of ancient times and has drawn comparison with what in more recent times the Southern gentleman thought of those not his professional associates and especially of "greasy mechanics and chaffering merchants."

It is not so much that question is to be raised about the merit of the ideals and aspirations which became formalized as culture among the leisure class of landowners in ancient times. They found in the quiet life upon their estates the satisfactions which they craved. The doubt comes as to the perpetuation into modern times of the bitterness of mood engendered in them when the supremacy of their class began to be threatened by the entrepreneurs of trade. Then, through the written word, in use of which they were beyond competition, they poured out the antagonism and contempt they felt for the merchants whose growing influence and power threatened the exclusiveness of the existing order. Thus there became frozen in classical literature definitions of what culture was and where it was to be found which have small relationship to the affairs of the changed world of today.

Even after we have granted the unloveliness of the buccaneering crews who ranged up and down the Mediterranean, it still remains true that in their courage to take great risks and in their responses to the challenge of adventure and in their insatiable curiosity which carried them to unknown lands and among strange peoples in search of goods to sell they developed characteristics which, transmitted to succeeding generations, made for qualities in life which could not have been spared.

Regardless of this, the analogies in modern life to conditions of the olden times are too few for us to accept unquestioned a conception of culture which, in its aesthetic responses, for instance, utilizes but few of the sanctions available in conditions of modern times. Not for a moment would I take exception to the spirit which finds itself uplifted by intimate acquaintanceship with great poems and literature, with great art and music, or with great sculpture and architecture. Likewise, I would insist that the man who spends four years in our north country here and does not learn to hear the melody of rustling leaves or does not learn to love the wash of the racing brooks over their rocky beds in spring, who never experiences the repose to be found on lakes and river, who has not stood enthralled upon the top of Moosilauke on a moonlight night or has not become a worshipper of color as he has seen the sun set from one of Hanover's hills, who has not thrilled at the whiteness of the snow-clad countryside in winter or at the flaming forest colors of the fall—I would insist that this man has not reached out for some of the most worth-while educational values accessible to him at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

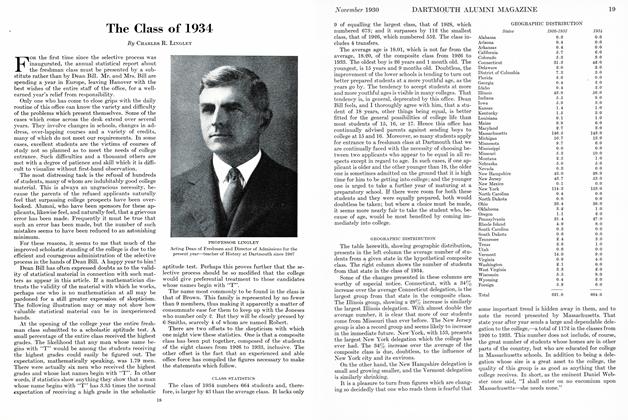

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

November 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1913

November 1930 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1920

November 1930 By Allan M. Cate -

Article

ArticleA Course in the Department of Biography

November 1930 By Harold E. B. Speight

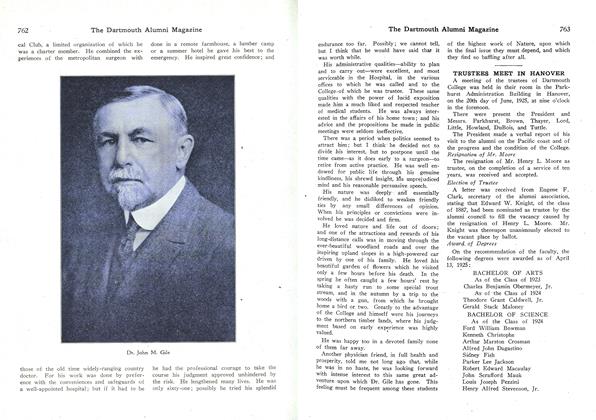

President Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleBELIEF

AUGUST, 1927 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleAN ACADEMIC HUNDRED THOUSAND

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleFACTUAL KNOWLEDGE IMPORTANT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleMIND VERSUS BRAIN

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleWIDENED BOUNDARIES

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleVALEDICTION

April 1934 By President Hopkins