The mind is a very different thing than the brain. A high-powered and aggressive mental capacity is a hazard to social welfare unless it be under the domination of a well-disposed mind. A dictionary definition of the word "mind" is that it is a collective term for all forms of conscious intelligence or for the subject of all conscious states. Thus, it appears that the mind of man differs not only among different individuals but in the same man at different times when his conscious states vary. It is not difficult to discover examples of this. The thinking of a man in good health is very different from his thinking when ill. The thinking of a man when tired is less accurate than of the same man when unwearied. Many a contrast might be mentioned, such, for instance, as that which exists between the mind untroubled and the one weighed down by anxiety. A man not acquainted with the conventions of social contacts or inexperienced in handling emotional stress may find the processes of his mind made inoperative at some critical time because of unfamiliarity with circumstances in which he is at the moment placed. It is not an infrequent thing to hear the assertion made of one or another that he is "of the same mind" or that he has "changed his mind."

True education has to do not only with mental development but likewise with establishment of external conditions which affect the mind and thus affect thinking. AmOng such external conditions are inspiration of environment, habits of health, avoidance of needless responsibility, attainment of mastery over one's nervous system, and cultivation of a sense of proportion which distinguishes between major and minor affairs of life. William of Wykeham, centuries ago, wrote over the portal of New College, "Manners makyth man." I once heard a distinguished scholar say derisively, "What an absurd motto for an educational institution." It loses any appearance of absurdity, however, if we supplement this with Ralph Waldo Emerson's statement, "good manners are made up of petty sacrifices." There is no requirement more essential to the life of the present day, when lessened distances have so greatly crowded men together, than that a spirit of accommodation to one's neighbor's habits and a consideration of his interests shall distinguish the educated man,—or any other, for that matter. The disposition to cultivate good manners and to accept petty sacrifices as indispensable therefor might induce within the race eventually a forbearance which would make peace an ideal of the spirit, inviting cooperation, rather than a militant propaganda, antagonizing and arousing controversy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

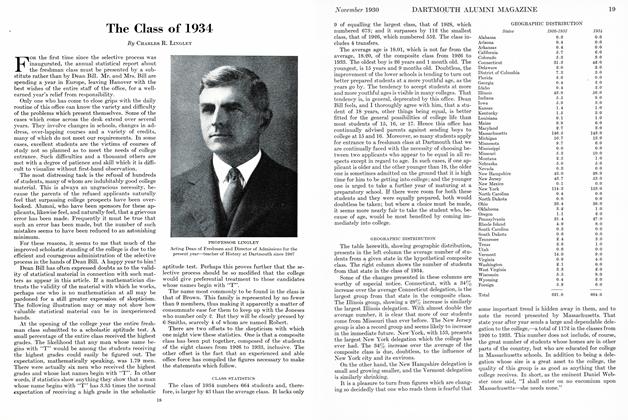

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Class Notes

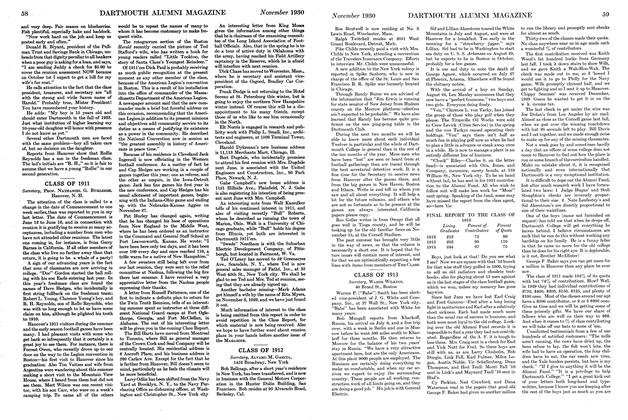

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

November 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1913

November 1930 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1920

November 1930 By Allan M. Cate -

Article

ArticleA Course in the Department of Biography

November 1930 By Harold E. B. Speight

President Hopkins

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate and His College

November 1928 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleThe Opening Address of Dartmouth's 162nd Year

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleAN ACADEMIC HUNDRED THOUSAND

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleFACTUAL KNOWLEDGE IMPORTANT

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

ArticleLIVING AS AN ART

November, 1930 By President Hopkins -

Article

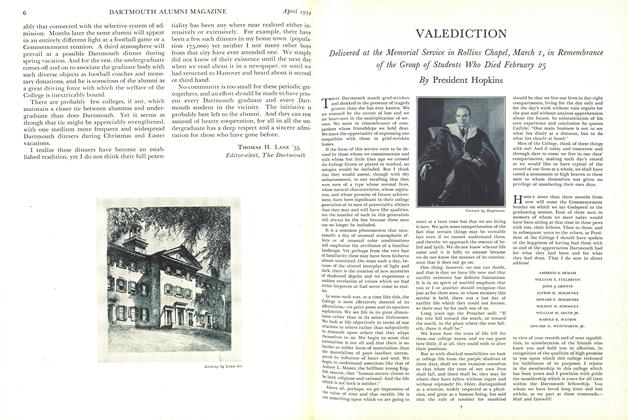

ArticleVALEDICTION

April 1934 By President Hopkins