The Department of English

ATYPICAL inhabitant of the United States begins to study English while he is a baby, and he continues to learn and to use it all day long, every day, until he dies. His knowledge of it is developed or called into service whenever he speaks, listens, reads, writes, meditates or dreams. It concerns him not only as an instrument by which his thoughts and emotions are expressed but also as a force that forms and enriches his entire character. During his childhood he discovers that the precise, vigorous, or imaginative English of books affords him pleasure and quickens his perceptions. He becomes aware of style, and of structural artistry, and of other elements that distinguish literature from ordinary reading matter. Long before he enters college, and long after he graduates, he may think of literature not as a subject in which to specialize but rather as a field which is every man's natural common ground.

These facts compel the teachers of English to assume a large but limited responsibility. Specialization in English must be of a different kind from specialization in most other subjects. The obvious purpose of literature is to afford pleasure to the reader, and this pleasure runs the risk of degenerating into pseudo-aesthetic comfort into a mere warm bath of emotional relaxation. But the true aesthetic pleasure, if properly cultivated, becomes a source of experience infinitely valuable. The distinguishing character of art is its power to fuse and harmonize all sorts of material, simple or complex or incongruous, into a definite intelligible unit. Thus literature is the key to many kinds of knowledge and to comprehension of the broadest as well as the most subtle and most elusive relationships among human beings. Wordsworth says that the essential character of the poet is that he is "a man speaking to men" and that the reader of poetry responds without being confined to the particular interests of a "lawyer, a physician, a mariner, an astronomer, or a natural philosopher." For this reason the function of literature is to connect and to interpret the special interests of different classes and professions and of different epochs in civilization. There is much truth in Wordsworth's assertion that "in spite of difference of soil and climate, of language and manners, of laws and customs, in spite of things silently gone out of mind, and things violently destroyed, the poet binds together by passion and knowledge the vast empire of human society, as it is spread over the whole earth, and over all time."

This function of literature cannot be thoroughly fulfilled unless the reader is prepared to appreciate the knowledge as well as the emotions of an author. The forces of literary genius are affected or determined by many kinds of historical, social and biographical circumstances; and unless the student applies himself to the understanding of these circumstances, the full value of the writer's genius cannot be realized. For example, Chaucer is a poet whose knowledge of human nature is as enjoyable and as enlightening today as it was five hundred years ago, but his essential modernity never becomes fully apparent until we have studied the language, social organization, and chivalric ideals of mediaeval England. Similarly, Shakespeare's value to us is proportionately increased when we study him in the light of Elizabethan literary fashions and the conditions of the theater. Nor is it possible to reach a full understanding of a twentieth century writer without regard to the social and intellectual currents of thought in our own time.

The requirements in English at Dartmouth are based upon the belief that some familiarity with every chronological period is desirable. Since one of the great values in literature is its power to interpret the universal and permanent importance of human life in past epochs, a student who neglects literature written earlier than his own generation loses a large part of his inheritance. Modem and contemporary literature is no less important than that of previous centuries and the department offers several courses in which the writers of our own day and of recent years are studied as interpreters and as innovators of ideas dominant in the modern world. So far as possible, the student is advised to elect courses in accord with his personal needs and tastes, rather than according to any uniform prescription.

The department believes that the study of literature is made more vital and effective when a student maintains the habit of casting his convictions and perceptions into written form. For this reason all of the courses in literature lay considerable emphasis upon composition. Furthermore, for students especially interested in critical or creative writing the department offers a variety of composition courses in journalism, the short story, the drama, and criticism.

In planning and grouping his courses a student has a wide field of choice, especially in senior year. Sixteen courses are offered for juniors and eighteen for seniors. It would require too much space to describe these courses in detail. The total number of courses in English required for the major program is ten; i.e., two in each semester of junior year and three in each semester of senior year.

Men, who at the end of sophomore year have attained a general point-average of 2.6 may become members of the honors group if they so desire, and if their candidacy is approved by the department and by the faculty Committee on Educational Policy. As a rule, the English honors group will be limited to men whose point-average in freshman and sophomore English courses is 2.7 or higher. The general intention of the honors work is to encourage men to self-reliance in the acquirement of education largely by their own efforts, without an elaborate mechanical system of check-reins and spurs. The assumption is that the honors student not only can but will work harder and learn more than the average student. He undertakes honors candidacy of his own volition; if he dislikes it after trial, he can drop back into the general major-group without upsetting his college career. Tutorial guidance and supervision are the chief feature of the honors program. Each student is assigned to some member of the department, with whom he meets once a week for an hour s conference; and he is not required to attend classes in his major courses. The tutor is responsible for ascertaining whether the work done is consistently of high grade (not less than B) but his principal function should be friendly, informal direction and encouragement. At each weekly conference, the student reads aloud an essay (approximately 1500 words) which he has written on a topic approved by the tutor. During junior year, the topics of these essays are in English literature from Beowulf to the close of the 17th century; during senior year, in English and American literature from 1700 to the present. So far as possible the topics follow a chronological sequence, and the program as a whole traces chronological developments, with regard to historical and social background as well as to literature and language. The purpose, however, is cultural, not technical; students are not expected to specialize as if they were members of the graduate school in a university. During the year 1930-31, emphasis will be put only on a few important authors, and their lesser contemporaries will not be studied in detail.

All students majoring in English, whether in the honors group or in the general group, are privileged to make use of Sanborn House. In this building the living room on the main floor will be open afternoons and evenings as a place of resort for conversation and informal conferences among the students and members of the department.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMy Love for Languages

August 1930 By Dr. James A.Spalding '66 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

August 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Lettter from the Editor

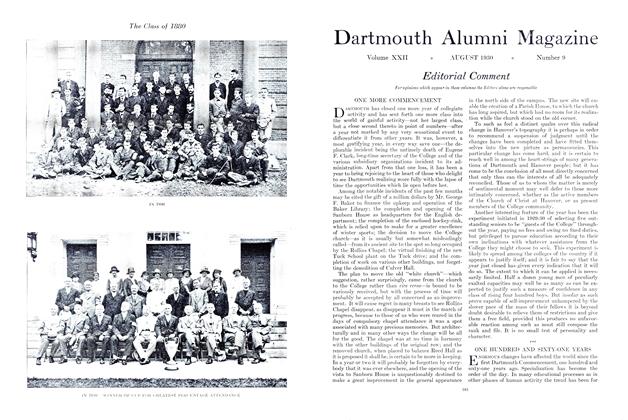

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

August 1930 -

Article

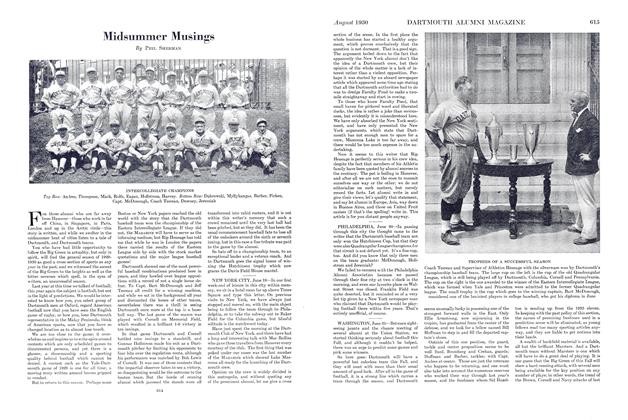

ArticleMidsummer Musings

August 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Article

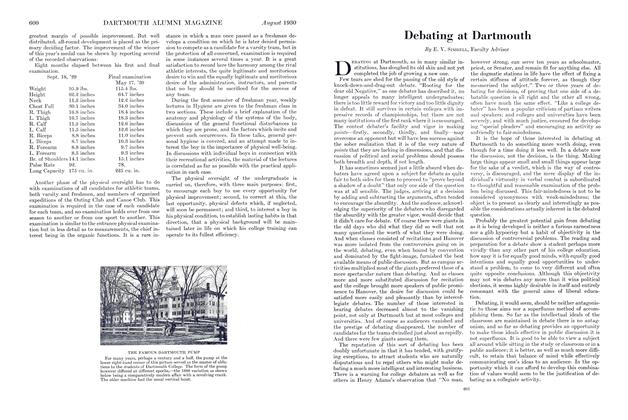

ArticleDebating at Dartmouth

August 1930 By E. V. Simrell, Faculty Advisor -

Article

ArticleAgain Among the Hills

August 1930 By Arthur Dewing