A study of the nature of Sociologyin the light of The Positive Politics of Auguste Comte. By McQuilkin DeGrange, Professor of Sociology, Dartmouth College. The Sociological Press, Hanover, Minneapolis, Liverpool, 1930. 214 pp.

The title of this very interesting book is misleading. The curve of societal movement is in a sense the climax of the exposition, but its discussion occupies only a small portion of the text. Moreover the title has a highly technical sound, whereas the contents is of considerable general scientific and philosophic interest (witness the selection as reviewer of a man who is not a sociologist). Hence, the misleading title would seem to be also unfortunate: A large circle of potentially interested readers is likely to be lost. The subtitle (A study, etc.) is much better. To summarize the contents in a brief re- view is manifestly impossible; for, though brief, the book contains much. To tell briefly what it is about and thereby to offset the implications of the title and to make a little more precise the scope suggested by the subtitle is, however, practicable.

As to the author's purpose let him speak for himself: "What is sociology? Despite all the efforts that have been made since the time of Comte, this question still remains unanswered. The failure has thrown discredit upon the whole attempt to discover law in the realm of social phenomena. It embarrasses the student of sociology and keeps him on the defensive when his right to be considered as a man of science is challenged. . . . . (This volume) seeks to formulate a new definition of sociology, a definition that shall grow logically out of the work of the man who first clearly saw the need and the possibility of a science of social phenomena. . . . Back to Comte, then . . .

not back to the Comte of the Positive Philosophy, . . . (but) to the product of the maturest thought of the great philosopher; ... to the Comte of the Positive Politics."

Many writers have regarded the later works of Comte beginning with the PositivePolitics as a retrogression rather than an advance. The author comes vigorously to the defense of his master and seeks to show with an abundance of quotation and documentation that the neglect of these later writings is nothing less than shameful, that it is in them that his genius burned with the brightest flame, and where he left his most significant message to mankind. With such enthusiasm and valor does the author attack this phase of his task that one is almost led to believe it to be the author's principal purpose.

This would, however, put appearance before reality. His fundamentally important purpose is as he states "to formulate a new definition of sociology." Fundamental in his discussion is the distinction between an abstract and a concrete science; and, it should be observed, it is as an abstract science that he seeks to define sociology. In Gomte's (later) hierarchy of the (abstract) sciences there are only seven: Mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, sociology, morals, and in this order, an inherent logical order of development, an order of increasing complexity. In order to make clear his point of view the author finds it necessary to give a rather full discussion of the principles underlying this classification, of the nature of an abstract science, and of Science as a whole; he also gives an historical sketch of the development of these sciences. Here lies the general scientific and philosophic interest of the book. It can be cordially recommended to any one interested in the history of scientific thought and its philosophic attributes. This does not mean that the reviewer altogether agrees with the author. For he doesn't. He is, for example, dubious as to the validity of the conception of a hierarchy of the sciences; it seems to him to involve an oversimplification; the development of the sciences does not seem to him to be a simple sequence, but at least a network. And there are other questions he looks forward to thrashing out with the author. But it does mean that the book is highly stimulating, that it is closely and trenchantly reasoned, and will provide food for vigorous thought to any one interested in the problems it discusses. It is perhaps precisely because he doesn't altogether agree that the reviewer feels like recommending it to others. For it is surely true that a book with which one agrees throughout is hardly worth reading.

This reviewer is not qualified to comment on the technically sociological results of the book. He may perhaps venture so far as to say that to a layman the author's problem seems of prime importance and that his definition of the societal process appears not only logical and appropriate but potentially fruitful. The author generously gives the bulk of the credit for this definition to Comte and in part to Sumner; but one strongly suspects that the definitive formulation is due to the author's own trenchant analysis. May it help to hasten the day when sociology will be universally accepted as a science.

CAMPUS CORNER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMy Love for Languages

August 1930 By Dr. James A.Spalding '66 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

August 1930 By Frederick W. Andres -

Lettter from the Editor

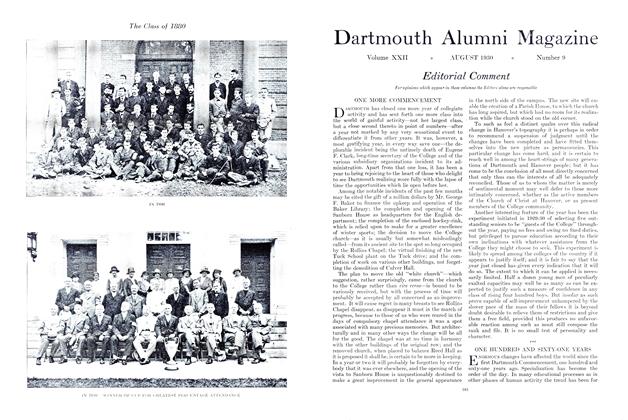

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

August 1930 -

Article

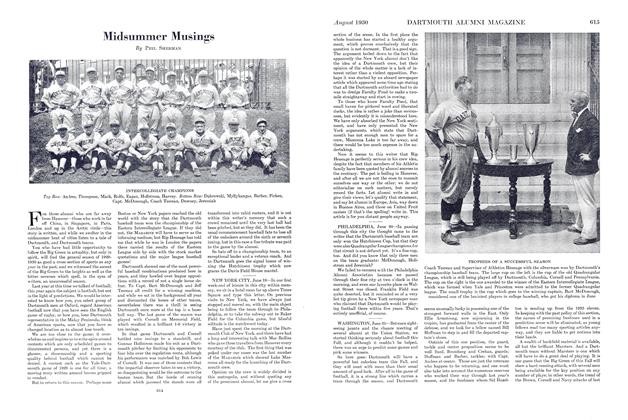

ArticleMidsummer Musings

August 1930 By Phil Sherman -

Article

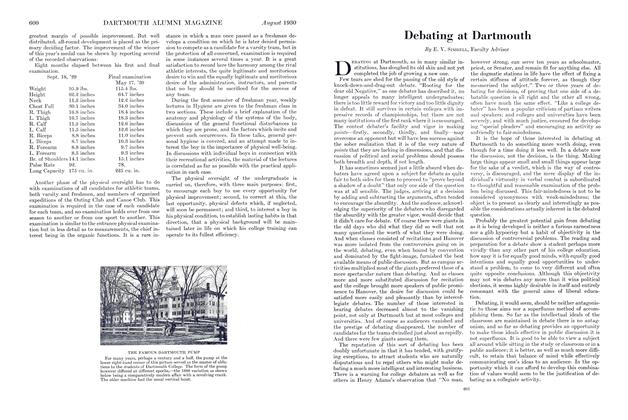

ArticleDebating at Dartmouth

August 1930 By E. V. Simrell, Faculty Advisor -

Article

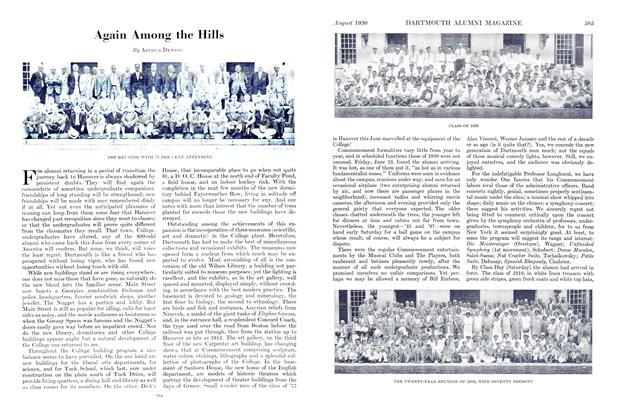

ArticleAgain Among the Hills

August 1930 By Arthur Dewing

Books

-

Books

BooksSpinning Spheres a Story of Copernicus

April1935 -

Books

BooksWINGS IN THE NIGHT

November 1938 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Books

BooksAN INTRODUCTION TO LABOR.

November 1954 By HARRY P. BELL -

Books

BooksAMERICAN HERETICS AND SAINTS

November 1938 By John M. Mecklin -

Books

BooksWAGON WHEELS: A STORY OF THE NATIONAL ROAD.

November 1956 By MARCUS A. MCCORISON -

Books

BooksASPECTS OF CRITICISM, LITERARY STUDY IN PRESENT-DAY GERMANY.

JANUARY 1969 By STEPHEN G. NICHOLS JR. '58