IN 1923 there were only a few handfuls of people who made personal use of motion pictures. Although professional movies had nearly reached their height of development in the silent form in the field of entertainment, there was practically no individual use of the motion picture medium. In 1923 and 1924, noninflammable motion picture film, sixteen millimeters wide, and simplified cameras and projectors were put on the market and since that time over four hundred thousand users of amateur movies have developed. A new field of recreation and a new medium of expression for the individual were made available.

Whether one would agree or not with the statement that the motion picture is an art form, one certainly cannot deny that it is a medium of expression —a means of conveying ideas and emotions. In this respect, at least, the motion picture belongs in the same category as the seven older arts. It is the only one of this category that was discovered after the industrial revolution and, immediately upon its discovery, it was commercialized. Unlike any of the other mediums of expression, it was unaccompanied by a corresponding amateur development, until comparatively recently. The amateur contingent that has supported the professional musical world, the legitimate stage and the field of literature, has been, in the past, entirely lacking in motion pictures. The movie was not, until recently, rooted in the people. We went to see films that were commercially produced as entertainment but we never made them. Only in isolated cases has the professional use of motion pictures represented individual or class viewpoints or interests. The only wide use to which commercial industry has put motion pictures is theatrical entertainment. Indeed, even today, the great mass of people think of motion pictures only in that light.

Since the box office is used as the criterion of subject matter and taste in professional motion pictures and since everyone who is able to pay fifty cents has a vote, one would logically conclude that professional movies represent the people. Following that thought, one would expect that the development of the amateur motion picture field would closely parallel that of the professional. Peculiarly enough, the amateur has not modelled himself on the professional but has entered new fields.

Amateur movies have a very limited history. Although experiments with their possibilities have been conducted since the beginning of motion pictures, it was not until very recently, when the activities of the largest photographic firms in the world culminated in the production of two narrow film widths with suitable cameras and projectors, that motion pictures could be practicably made by individuals at greatly reduced cost. In addition to the economy effected by the use of a narrower film than the standard 35 millimeter professional width, an almost equal economy was secured by the introduction of the reversal process whereby the need of two film strips to secure a positive for projection was eliminated. In addition to this, at the beginning of the amateur filming movement, central processing and developing stations were installed, handling the film with far greater efficiency that would otherwise be possible. These factors still remain the most marked points of difference between amateur motion pictures and all other forms of photography. To be more specific, a still camera practitioner must take his negatives to a local laboratory for development and printing of positives, while the amateur motion picture photographer's reel is sent to a central station within the region. The professional cinematographer uses positive and negative film, necessitating duplicate film strips and much higher costs, while the amateur requires but one film.

Although recent, the development of amateur movie equipment has been both rapid and thorough. In 1925, only a few cameras and projectors were on the market with a minimum of accessories. Today, every possible accessory to free the amateur of incidental chores is offered. Turret mounted cameras, a wide range of lenses, cameras with several speeds, panchromatic film, a wide variety of screens, improved and vastly more powerful projectors, all types of lighting equipment for interior work and editing and titling services are all provided for the amateur. In addition, by far the most realistic and beautiful of all motion picture color processes is exclusively the amateur's own. Mechanical devices have been supplied to insure correctness in the two bugbears of all, photography, exposure and focus.

Film libraries have been developed to bring every type of film for projection into the amateur's home. Equipment and films for the projection of synchronized and talking movies may be had. Cameras and projectors, of many types, now range in price from as low as twelve dollars to as high as twelve hundred, meeting all purses and all needs.

Amateur motion pictures have brought technical advances never secured for professional films. This field has required only a little over five years to bloom very fully and it has progressed far more rapidly than other branches of photography. The chief reasons for this are, of course, the groundwork of experience of still photography and of the professional movie which lies behind us. Another reason may be found in the fact that amateur movie making is one of the most thoroughly organized of the world's personal activities. The Amateur Cinema League, a noncommercial organization of the world's amateur cameramen, of which Hiram Percy Maxim, the inventor, is president, has members in more than fifty-five countries. It has solidified amateur movie making interests and has directed the tenor of their development. No other hobby field is so well represented by a single association, with the exception of amateur radio, also under the presidency of Mr. Maxim. The Amateur Cinema League supplies aid and information to movie amateurs, publishes a monthly magazine covering the field and prints and distributes periodical monographs to its members all over the world, some of which have been translated into several foreign tongues. It aids amateur movie makers in the purelyrecreational use of film and in many of the more serious purposes for which film is employed.

Amateur movie workers have had ample aid from their professional brethren, but the two movements are not closely allied. Amateurs have been given generous cooperation from the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, under the leadership of Will H. Hays, and from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the professional association of directors, actors and other technicians. Not a few amateurs have entered the professional field and the amateur ranks include many roving cameramen whose product is eagerly purchased for professional use. In spite of this and with complete good will on both sides, the two fields have practically nothing in common. Amateur movie makers are not among those who storm the gates of Hollywood, seeking jobs behind or before the professional camera. Individual users of movies are rarely professional movie fans. One might have expected that the amateur cinema movement would have followed in the train of the professional movies as the little theatre movement has followed the professional legitimate theatre, but this is true to a very limited extent. Only a few groups have produced photoplays modelled on the Hollywood product and, in the majority of cases, these have a flavor of the burlesque.

What, then, are amateurs doing with their personal motion picture equipment? The great part of the film exposed each year is probably used to record personal and topical subjects. Amateur cameramen naturally hasten to film their families, their relatives and their friends. Every personal film library has its share of purely personal film. A good deal of it may be rather dull to a stranger attending a home movie program, but it has the greatest personal importance. Years from now, when children are grown up or when others have passed away, their images in lifelike motion can be recalled from the past. No form of still photography can preserve personality—the tricks of facial expression, the little gestures and the characteristic mannerisms, as can motion pictures.

After the average movie maker has filmed family and friends and ha,s started film diaries of his growing children, he turns his camera to record his vacations, to preserve for himself the happiness of the annual breaks in his routine. On his European trip, on the fishing trip to Maine, on the winter trip to California or Bermuda and on the trip around the world, he takes his movie camera and makes a motion picture record of his pleasure. Hundreds of thousands of feet of film are exposed each year and special processing and service stations have been set up in European, Asiatic and African capitals chiefly to serve the American movie making tourist. Every boatload of travelers carries hundreds of amateur cameras that will be used to bring back a living history of a trip, a record beside which still photographs are limited and cold. Out of the vast amount of film exposed by traveling movie makers, hundreds of beautiful travel pictures are made each year, pictures that are carefully edited and that vie with the best that professionals can produce in interest and photographic perfection.

All outdoor sports are opportunities for the movie camera and sport filming is one of the most popular of personal movie making activities. There are amateur made reels of every sport from volley ball to polo. Golf is, naturally, the most popular and studious fans have made slow motion picture analyses of their strokes. In other fields of sport, the amateur motion picture camera is used as a means of study of technique as well as of record and preservation of entertainment.

Topical films or newsreels are prominent on the amateur screen. Local events—the opening of a new building, the fire in the next block, the visit of a celebrity or the lodge parade are all material for the amateur camera. With hundreds of thousands of movie makers in all parts of the world, it is to be expected that some of their number will have the opportunity to film events that escape the professional cameraman. Amateurs have so often "scooped" the newsreels that this has ceased to be a point of particular moment. Amateur records are being made of many of the outstanding events of the present. A 16 mm. camera, as well as a professional, filmed the Byrd Antarctic Expedition. Amateur movie clubs in different cities have cooperated to make complete film records of air derbies and transcontinental flights. In other clubs, amateur cameramen have worked together to produce complete film studies of their respective cities. Thousands of amateur made photoplays have been filmed. Often these film dramas are produced for or by the youngsters in the family but many of them are more serious in intent. Clubs have been organized for the regular production of photoplays similar to the community player groups. Dramatic films so produced have been exchanged internationally and there exists a regular distribution system for them. Amateur movies, like other hobbies with definite techniques, has its advanced enthusiasts who are masters of camera magic. The trick work, the illusions and lighting effects of the professional are all available to the amateur and many technically minded cinematographers specialize in these fields. The motion picture is at its best in illusion and anything can be represented through its means. Impossible fairy tales become realities on the amateur's screen.

Using the capacities of the motion picture which are shared by no other medium of expression, many amateurs have experimented with movies as an art form. Outstanding productions like The Fall of the House ofUsher, The Gaiety of Nations and H2O are from amateur ateliers. Such films have won recognition from professional studios; for example, The Fall of theHouse of Usher, produced by J. S. Watson and Melville Webber, was acclaimed by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures as one of the most significant steps in the development of the motion picture as an art medium.

Business and professional men were not long in discovering that their hobby had other potentialities than recreation and the preservation of the living images of their families and friends. As the instrument of the individual, the amateur movie camera has entered almost every business and industry. Formerly, industrial and business movies could be made only by commercial companies working with the professional studio technique. Business films were, necessarily, expensive and only the very large industries could afford this medium of advertising or instruction. With the advent of the amateur camera, every business man, every salesman and every industrial instructor became his own producer, if he was so minded. Now, film records, publicity films, and scientific studies are made in profusion and at a low cost hitherto impossible. The increase of the use of the motion picture camera in business and in the laboratory has brought with it entirely new uses and services. In the hands of amateurs, cameras are used to study industrial efficiency, to record the speed of a descending elevator, to cite one instance; to furnish a living picture of the construction of New York's skyscrapers, to cite a second; and to tell the story of the preparation of rubber, the manufacture of typewriters or the drilling of oil wells.

A movie amateur in a municipal government is making a film record of traffic snarls for later analysis, while the retailer has a continuous film display in his window, the product of his own photography. The United States government is reducing its vast film libraries to 16 mm. film size and is making them available without charge for home projection. The modern welfare appeal is made with a 16 mm. movie produced by the patrons of the project. The Amateur Cinema League gives detailed aid in making pictures of this type as it does in purely personal filming. In the last few months, over one hundred and twenty-five such films have been completed under its guidance.

The amateur camera and projector are entering the field of education more slowly but, even there, they have made more progress than in the whole previous history of motion pictures. For the first time, properly controlled and scientifically planned teaching films are made on an adequate scale.

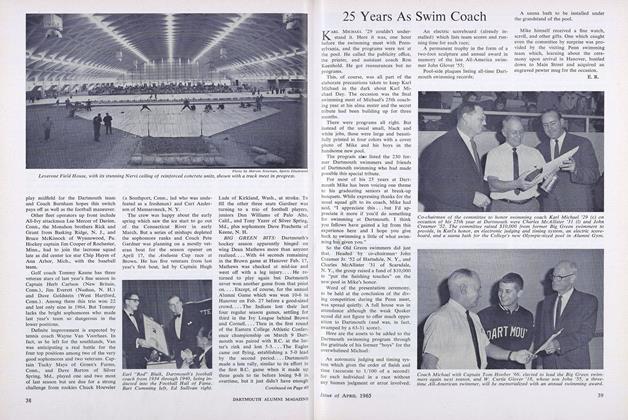

Via sport films, amateur movies have entered the service of colleges and universities. Many colleges, like Dartmouth, have undertaken regular film releases for the benefit of the alumni. In this effort, prestige definitely belongs to Dartmouth for its Alumni Newsreels, which are the most complete and the most regular of all. College athletics and extracurricular activities are filmed and combined with scenics of the campus and classroom; film stories of ski trips and outing club hikes are offered to the alumni. Those who have seen the Dartmouth news releases will realize that there is no better way to keep an effective memory of the College alive. Other than as a service to alumni and a means of publicity for the college, amateur movies are being used in a wide variety of ways. At medical schools they have invaded the classroom and films of operating and dissection technique are screened for students. At the Princeton Observatory, a film study of the use of the telescope was made and, by means of a specially built camera, 16 mm. astronomical films have been produced by students. The amateur film, Sunrise on the Moon, made at Princeton University, presents an astronomical drama impossible in any other medium than the motion picture. In the physics laboratories at Princeton and Leland Stanford, film records of experiments have been made and similar pictures have been filmed in numerous other educational institutions.

The amateur camera has been found to be an invaluable adjunct to coaching. Dartmouth cinematographers recently filmed every move in a football game for the purpose of subsequent analysis. Most athletic managers of the larger colleges have used 16 mm. movies similarly and the personal movie camera has been found to be a very accurate scouting reporter.

Colgate, Leland Stanford, The University of Southern California and both Cambridge and Oxford have seen student made amateur photoplays produced on their campuses. Such photoplays permanently preserve the work of undergraduate player clubs and make it possible for these films to be placed on a distributing chain and to be seen by numbers of alumni who would otherwise miss them. Expenses are generally lower than in the production of a similar legitimate drama, because exteriors and actual sets may be used, which further add interest to the drama for alumni and members of the college.

Professional movie publicity, featuring staggering production costs, has become such a definite part of our consciousness of motion pictures that it may be difficult to think in terms other than those. Whenever the production of a photoplay is mentioned, the professional studio hierarchy is envisioned and monstrous expenses are seen. There is hardly a better example of our national gullibility to high powered ballyhoo. Amateur movies have done a great deal to break up this concept. The study and resistless infiltration of the inexpensive 16 mm. camera and projector, operated by those whose only salary is the pleasure they derive from the results they achieve or the benefit to their major interests, is gradually changing our ideas. The old concept still exists, but, to a considerable extent perhaps, the truth of the matter may be apparent from the fact that one of the best amateur photoplays ever made, rating theatrical screenings, cost a total of but ninety-eight dollars.

At present, an amateur may fill out a home movie program with reduction prints of either silent or talking professional pictures, but, except in isolated cases, he cannot make his own talkies. The amateur and individual use of the motion picture has not yet demanded 16 mm. talkies, except for projection on home programs. Movie makers are still exploring the possibilities of silent films and, in many amateur fields, they will never be supplanted by talkies. However, amateur equipment for making talkies and sound pictures is just around the corner. It will probably find its greatest use in certain industrial and educational fields and in amateur dramatics. In this respect, the 16 mm. field again profits by its isolation from the professional movie, for there need be no period of expensive experimentation, no rush to keep up with other exhibitors or producers.

Movies have a universal and omnipotent fascination. They may serve the professional "fan" as ephemeral entertainment and they may serve the scientist in making grave and serious analyses. The motion picture is not in itself anything but an excellent medium and, in that respect, it can be compared to the written word better than anything else. One may use a movie camera to record or express practically anything that might be expressed in writing, with the exception of abstract thought that cannot be pictorially represented. In many other ways, it is a more powerful medium than the written word.

We already have the real essence of the motion picture. The future can bring only mechanical perfections —entirely natural color, stereoscopic quality and, perhaps, the ability to project movies by radio waves. However, even more important than these phenomena is the development of the use of motion pictures by individuals with the vast new range of service which has come with them.

MOVIES OP YOUR GOLF SWING As an aid to beating par

AMATEUR MOVIES Made of gliding, for student instruction

POLICE TRAINING Furthered by use of instructional 16mm. films

OPER ATIVE TECHNIQUE Taught with the aid of amateur m ovies. This is a photograph from a 16mm. film

EDITING AND TITLING

AT PRINCETON An amateur movie made on the campus

AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY A scene from an undergraduate movie production, "The Fast Male"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

March 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

March 1931 -

Article

ArticleFebruary News of the College

March 1931 -

Article

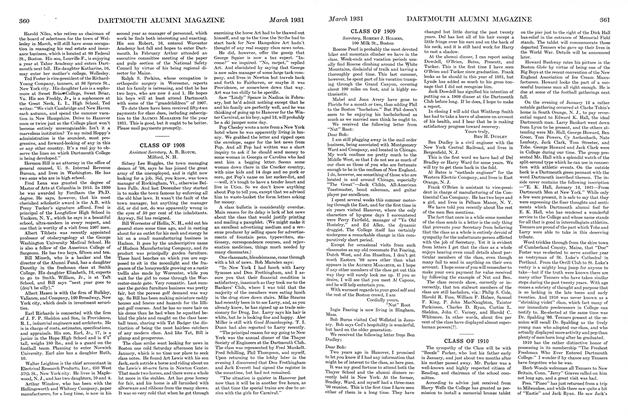

ArticleThe College and Physical Fitness

March 1931 By William R. P. Emerson, M. D. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

March 1931 -

Class Notes

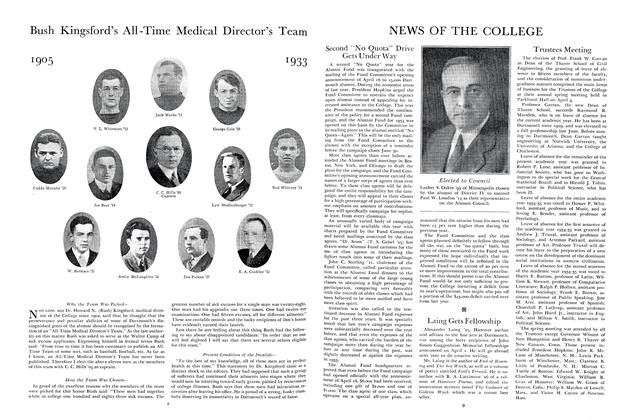

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

March 1931 By Arthur E. McClary, Malone, N. Y., Herford N. Elliott