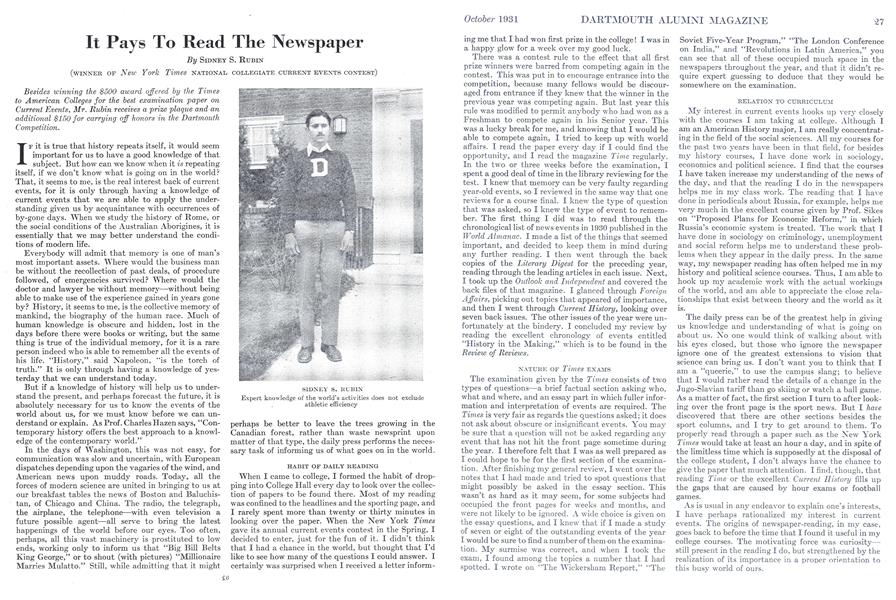

(WINNER OF New York Times NATIONAL COLLEGIATE CURRENT EVENTS CONTEST)

Besides winning the $500 award offered by the Timesto American Colleges for the best examination paper onCurrent Events, Mr. Rubin receives a prize plaque and anadditional $150 for carrying off honors in the DartmouthCompetition.

IF it is true that history repeats itself, it would seem important for us to have a good knowledge of that subject. But how can we know when it is repeating itself, if we don't know what is going on in the world? That, it seems to me, is the real interest back of current events, for it is only through having a knowledge of current events that we are able to apply the understanding given us by acquaintance with occurrences of by-gone days. When we study the history of Rome, or the social conditions of the Australian Aborigines, it is essentially that we may better understand the conditions of modern life.

Everybody will admit that memory is one of man's most important assets. Where would the business man be without the recollection of past deals, of procedure followed, of emergencies survived? Where would the doctor and lawyer be without memory—without being able to make use of the experience gained in years gone by? History, it seems to me, is the collective memory of mankind, the biography of the human race. Much of human knowledge is obscure and hidden, lost in the days before there were books or writing, but the same thing is true of the individual memory, for it is a rare person indeed who is able to remember all the events of his life. "History," said Napoleon, "is the torch of truth." It is only through having a knowledge of yesterday that we can understand today.

But if a knowledge of history will help us to understand the present, and perhaps forecast the future, it is absolutely necessary for us to know the events of the world about us, for we must know before we can understand or explain. As Prof. Charles Hazen says, "Contemporary history offers the best approach to a knowledge of the contemporary world."

In the days of Washington, this was not easy, for communication was slow and uncertain, with European dispatches depending upon the vagaries of the wind, and American news upon muddy roads. Today, all the forces of modern science are united in bringing to us at our breakfast tables the news of Boston and Baluchistan, of Chicago and China. The radio, the telegraph, the airplane, the telephone—with even television a future possible agent—all serve to bring the latest happenings of the world before our eyes. Too often, perhaps, all this vast machinery is prostituted to low ends, working only to inform us that "Big Bill Belts King George," or to shout (with pictures) "Millionaire Marries Mulatto." Still, while admitting that it might perhaps be better to leave the trees growing in the Canadian forest, rather than waste newsprint upon matter of that type, the daily press performs the necessary task of informing us of what goes on in the world.

HABIT OF DAILY READING

When I came to college, I formed the habit of dropping into College Hall every day to look over the collection of papers to be found there. Most of my reading was confined to the headlines and the sporting page, and I rarely spent more than twenty or thirty minutes in looking over the paper. When the New York Times gave its annual current events contest in the Spring, I decided to enter, just for the fun of it. I didn't think that I had a chance in the world, but thought that I'd like to see how many of the questions I could answer. I certainly was surprised when I received a letter informing me that I had won first prize in the college! I was in a happy glow for a week over my good luck.

There was a contest rule to the effect that all first prize winners were barred from competing again in the contest. This was put in to encourage entrance into the competition, because many fellows would be discouraged from entrance if they knew that the winner in the previous year was competing again. But last year this rule was modified to permit anybody who had won as a Freshman to compete again in his Senior year. This was a lucky break for me, and knowing that I would be able to compete again, I tried to keep up with world affairs. I read the paper every day if I could find the opportunity, and I read the magazine Time regularly. In the two or three weeks before the examination, I spent a good deal of time in the library reviewing for the test. I knew that memory can be very faulty regarding year-old events, so I reviewed in the same way that one reviews for a course final. I knew the type of question that was asked, so I knew the type of event to remember. The first thing I did was to read through the chronological list of news events in 1930 published in the World Almanac. I made a list of the things that seemed important, and decided to keep them in mind during any further reading. I then went through the back copies of the Literary Digest for the preceding year, reading through the leading articles in each issue. Next, I took up the Outlook and Independent and covered the back files of that magazine. I glanced through ForeignAffairs, picking out topics that appeared of importance, and then I went through Current History, looking over seven back issues. The other issues of the year were unfortunately at the bindery. I concluded my review by reading the excellent chronology of events entitled "History in the Making," which is to be found in the Review of Reviews.

NATURE OF Times EXAMS

The examination given by the Times consists of two types of questions—a brief factual section asking who, what and where, and an essay part in which fuller information and interpretation of events are required. The Times is very fair as regards the questions asked; it does not ask about obscure or insignificant events. You may be sure that a question will not be asked regarding any event that has not hit the front page sometime during the year. I therefore felt that I was as well prepared as I could hope to be for the first section of the examination. After finishing my general review, I went over the notes that I had made and tried to spot questions that might possibly be asked in the essay section. This wasn't as hard as it may seem, for some subjects had occupied the front pages for weeks and months, and were not likely to be ignored. A wide choice is given on the essay questions, and I knew that if I made a study of seven or eight of the outstanding events of the year I would be sure to find a number of them on the examination. My surmise was correct, and when I took the exam, I found among the topics a number that I had spotted. I wrote on "The Wickersham Report," "The Soviet Five-Year Program," "The London Conference on India," and "Revolutions in Latin America," you can see that all of these occupied much space in the newspapers throughout the year, and that it didn't require expert guessing to deduce that they would be somewhere on the examination.

RELATION TO CURRICULUM

My interest in current events hooks up very closely with the courses I am taking at college. Although I am an American History major, I am really concentrating in the field of the social sciences. All my courses for the past two years have been in that field, for besides my history courses, I have done work in sociology, economics and political science. I find that the courses I have taken increase my understanding of the news of the day, and that the reading I do in the newspapers helps me in my class work. The reading that I have done in periodicals about Russia, for example, helps me very much in the excellent course given by Prof. Sikes on "Proposed Plans for Economic Reform," in which Russia's economic system is treated. The work that I have done in sociology on criminology, unemployment and social reform helps me to understand these problems when they appear in the daily press. In the same way, my newspaper reading has often helped me in my history and political science courses. Thus, I am able to hook up my academic work with the actual workings of the world, and am able to appreciate the close relationships that exist between theory and the world as it is.

The daily press can be of the greatest help in giving us knowledge and understanding of what is going on about us. No one would think of walking about with his eyes closed, but those who ignore the newspaper ignore one of the greatest extensions to vision that science can bring us. I don't want you to think that I am a "queerie," to use the campus slang; to believe that I would rather read the details of a change in the Jugo-Slavian tariff than go skiing or watch a ball game. As a matter of fact, the first section I turn to after looking over the front page is the sport news. But I have discovered that there are other sections besides the sport columns, and I try to get around to them. To properly read through a paper such as the New York Times would take at least an hour a day, and in spite of the limitless time which is.supposedly at the disposal of the college student, I don't always have the chance to give the paper that much attention. I find, though, that reading Time or the excellent Current History fills up the gaps that are caused by hour exams or football games.

As is usual in any endeavor to explain one's interests, I have perhaps rationalized my interest in current events. The origins of newspaper-reading, in my case, goes back to before the time that I found it useful in my college courses. The motivating force was curiosity still present in the reading I do, but strengthened by the realization of its importance in a proper orientation to this busy world of ours.

SIDNEY S. RUBIN Expert knowledge of the world's activities does not exclude athletic efficiency

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe College as a Cooperative Enterprise

October 1931 By Ernest Martub Hopkins -

Article

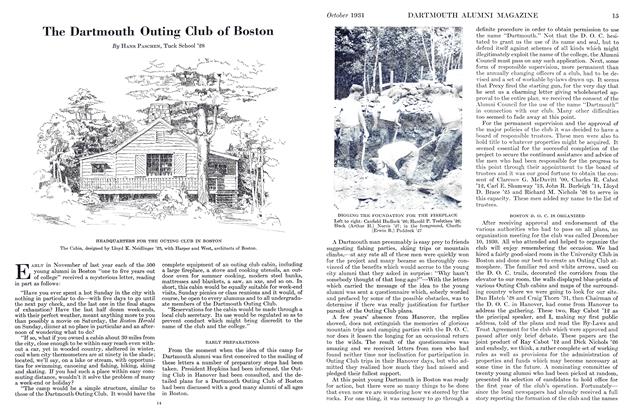

ArticleThe Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston

October 1931 By Hans Paschen, Tuck School '28 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

October 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1911

October 1931 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

Article

-

Article

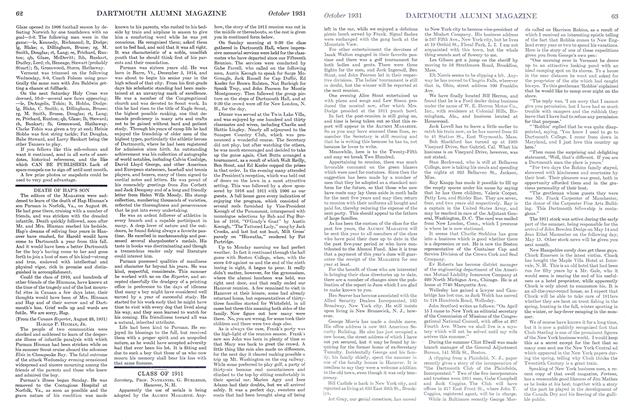

ArticleNORTH CHINA ALUMNI REDUCED IN NUMBERS

APRIL, 1927 -

Article

ArticleEnrollment Figures

November 1961 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

OCTOBER 1991 -

Article

ArticleSpring Sports Preview

May/June 2005 -

Article

ArticleREPORT FROM THE ATHLETIC COUNCIL

AUGUST 1930 By L. G. HODGKIN3 '00 -

Article

ArticleThe Admissions Problem Grows With Every Mail

February 1946 By Robert C. Strong '24