By Barrett Studley '16, New York. Macmillan. 257 pages. $2.00.

The tradition that represents soldiers as "strong, silent men" who prefer not to talk of their experiences runs up against a notable check in the case of aviators. No journalist out for copy ever turned away from an aviation squadron empty-handed. The aviator, in peace or wartime, however taciturn he may be on other subjects, will talk of flying as long as he can find breath to speak and ears to listen. Let it be understood that there is no boastfulness about it. Exploits or blunders, his own or others', are alike fair grist. He will tell of an ignominious crack-up with as much gusto as of bringing down an enemy ace. As a topic of conversation, flying outranks even golf and football.

"Learning to Fly for the Navy" is a "juvenile" that any adult addicted to barracks-flying can enjoy. Lieutenant Studley, who, as Chief Instructor at Pensacola, is very much of an authority on his subject, has cast the experiences of a student-flyer into a sort of Aviator's Progress. The plot is, as it should be, pleasingly meager, a mere framework on which typical incidents and a great deal of information about the nature and handling of planes are strung. Jim Brent, except that he is sufficiently lacking in omniscience and infallibility to be inoffensive, is the usual hero of juvenile fiction. Otis Marsteller, the villain, conceals his darker nature so successfully through the earlier parts of the book that the reader begins to suspect the author of an unfair prejudice against him, until in the climax he reveals the depth of his turpitude by trying to stretch a glide. Now many an otherwise honorable man—de mortuis nihil nisi bonum—has in the stress of the moment tried to turn back after a take-off; but to stretch a glide deliberately is so heinous a crime that even the layman will agree that Marsteller got off only too lightly. The whole moral of the book (and a very sound moral it is) is: "Keep flying speed." It is in his offense against this cardinal precept, much more than in his somewhat highhanded treatment of the hero, that Otis Marsteller's villainy lies.

Quite apart from its value as entertainment, "Learning to Fly for the Navy" has the merit of affording concise and interesting answers to the multitude of questions that non-flyers ask or would like to ask about the handling of aeroplanes. Jim Brent's instruction includes all phases of flying both seaplanes and land-planes, from the first take-off on dual-control, through loops, rolls, spins, Immelman's and wing-overs, to launching by catapult from the deck of a battleship. In the completeness and accuracy of its information and the emphasis that it places on the proper essentials, "Learning to Fly for the Navy" makes a very satisfactory allegorical manual of preliminary flying training. The numerous photographs with which the book is illustrated were taken under the author s supervision by a navy photographer attached to the training station and give the narrative a pleasant reality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe College as a Cooperative Enterprise

October 1931 By Ernest Martub Hopkins -

Article

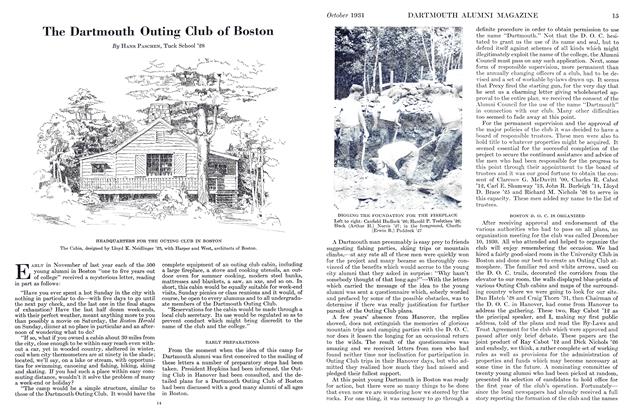

ArticleThe Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston

October 1931 By Hans Paschen, Tuck School '28 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1910

October 1931 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1930

October 1931 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS of 1911

October 1931 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh

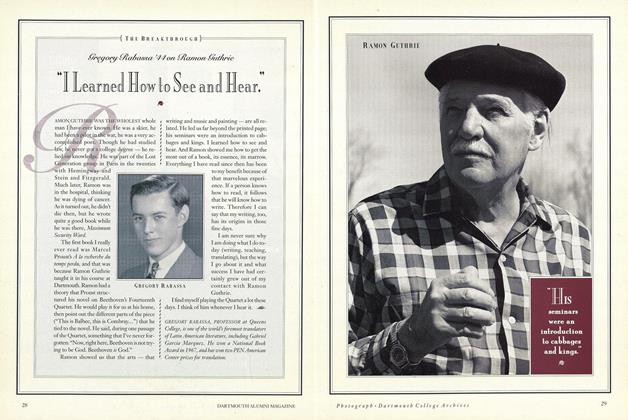

Ramon Guthrie

-

Books

BooksPRACTICAL FLIGHT TRAINING

November 1936 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksMAUPASSANT: A LION IN THE PATH

February 1950 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksTHE SELECTED LETTERS OF GUST AVE FLAUBERT.

May 1954 By RAMON GUTHRIE -

Books

BooksThe Back of My Mind

DECEMBER 1966 By Ramon Guthrie -

Feature

FeatureGregory Rabassa '44 on Ramon Guthrie

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ramon Guthrie

Books

-

Books

BooksCurse of Occupation

March 1980 By David Wykes -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

March 1952 By John B. Stearns '16 -

Books

BooksFIELDS OF GRACE.

APRIL 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHIRTY-FIVE DARTMOUTH POEMS.

JANUARY 1964 By PHILIP BOOTH '47 -

Books

BooksTANSTAAFL: THE ECONOMIC STRATEGY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS.

JULY 1971 By THOMAS B. ROOS -

Books

BooksROMANCE IN THE MAKING: CHRETIEN DE TROYES AND THE EARLIEST FRENCH ROMANCES.

January 1955 By VERNON HALL JR.