Translated and edited byFrancis Steegmuller '27. New York: FarrarStraus and Young, 1953. 281 pp. $4.00.

As a master of self-portraiture, Gustave Flaubert - whose tenet it was that the author's personality must be rigidly excluded from his work — ranks not too. far behind Stendhal and Montaigne; not only because he consistently and admittedly violated his rule in his novels but also because he is the author of a voluminous correspondence in which the "I" which he tried to banish from his novels gets its full revenge.

Mr. Steegmuller's Flaubert and MadameBovary, which appeared some years ago, establishes his rank as a student and lover of Flaubert. His dual purpose in editing this selection from Flaubert's correspondence is to acquaint American readers with the rich and passionate humanity of the French author and to underline the importance of his message for men of our day. These letters, he points out in his introduction, "provide effective ammunition" against the many pressures, secret and overt, that concert to destroy intellectual and artistic integrity in our own time, and constitute "probably the most complete statement in existence of the artist's duty to maintain his independence - a statement even more valid to-day than when Flaubert made it."

The succinct biographical and critical essays with which Mr. Steegmuller prefaces the various groups of letters furnish background and a pattern of continuity to the letters themselves. As a further assistance to the reader, the book includes biographical sketches of Flaubert's principal correspondents.

The dust jacket achieves a new standard for modesty in blurb-writing when it terms this book "the first comprehensive selection of Flaubert's correspondence to appear in adequate translation." The fact is that Mr. Steegmuller's renderings of Flaubert's prose are so much more than "adequate" that they read as one can only imagine they would have read if English had been Flaubert's mother tongue.

Any reader whose only contact with Flaubert is through Madame Bovary and who has had that mighty book soured for him by such prissy tributes as "perfect," "meticulous," etc., owes it to himself and to Flaubert, the hater of niceties, to discover the real Flaubert that lives in his letters.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE CREATIVE ARTS

May 1954 By IRWIN ED MAN -

Feature

FeatureSinging Ambassadors

May 1954 By ROBERT K. LEOPOLD '55 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Fire Bug

May 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureON THE AIR 16 Hours a Day

May 1954 By DONALD R. MELTZER '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1954 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE E. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON

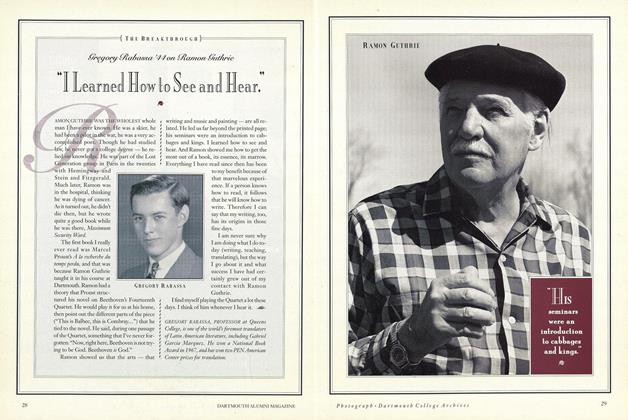

RAMON GUTHRIE

-

Books

BooksLEARNING TO FLY FOR THE NAVY

OCTOBER 1931 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksPRACTICAL FLIGHT TRAINING

November 1936 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksMAUPASSANT: A LION IN THE PATH

February 1950 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksThe Back of My Mind

DECEMBER 1966 By Ramon Guthrie -

Feature

FeatureGregory Rabassa '44 on Ramon Guthrie

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ramon Guthrie

Books

-

Books

BooksShelf Life

Sept/Oct 2004 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2013 -

Books

BooksJUDAISM DESPITE CHRISTIANITY. THE "LETTERS ON CHRISTIANITY AND JUDAISM" BETWEEN EUGEN ROSENSTOCK-HUESSY AND FRANZ ROSENZWEIG.

FEBRUARY 1970 By EDWARD MARTIN POTOKER '53 -

Books

BooksMelodies Lingering On

September 1980 By H. Wiley Hitchcock '44 -

Books

BooksHow YOU REALLY EARN YOUR LIVING.

October 1952 By L. G. Hines -

Books

BooksRELATION OF FAILURE TO PUPIL SEATING.

December 1932 By W. R. W.