By G. Walter Woodworth, Assistant Professor, Amos Tuck School, Dartmouth College. Ann Arbor, Michigan, University of Michigan Bureau of Business Research, 1932.

The banking crisis of 1933, which reached an especially acute point in Michigan, has made this statistical research on the Detroit money market a very pertinent and useful reference. The author has made a personal investigation of the Detroit banking situation covering a period of several years. He informs the reader that there is no money market in Detroit, in the sense of an "open" market. He then accounts for the important aspects of De- troit banking history and activity. Far from being a simple description of banking events, this study covers a multitude of statistics, which have been treated in a scientific fashion to distinguish seasonal, secular, and cyclical changes.

This research project provides much evidence of the unusually rapid and specialized business development of Detroit and of the banking problems arising out of this unique situation. For example, in the industrial and commercial background, it is stated that the population of Detroit grew from 285,704 in 1900 to 993,678 in 1920, an increase of 247.8 per cent. By 1930, the population had grown to 1,568,662, an increase of 57.9 per cent compared with 1920. This rate of growth was greatly in excess of the country as a whole. Similarly, the value of manufacturers in Detroit, in 1919, increased over 1904 by 862.9 Per cent; by 1929, the increase was 64.2 per cent over 1919. These changes were greatly in excess of those for other cities. Along with these rapid rates of growth, there appeared an alarming lack of diversity in Detroit's industries, with automobile and related lines of production representing 56.5 per cent of the total value of products in 1927. The industrial activity of the city showed wide fluctuations from time to time—particularly cyclical variations. Finally, the preponderance of the automobile industry has made Detroit essentially a manufacturing rather than a commercial city. In this environment, a large number of financial institutions started and were obliged to assume large and risky banking undertakings.

One of the distinctive features of the Detroit banking mechanism was the existence of home-city branch banking. In 1918, there were 12 banks in the city with a total of 122 branches. By 1930, there were only 9 banks but the total branches had risen to 311. Coexistent with the development of branch banking was the tendency toward concentration among banks. By 1932 there were only five banks in the city, which had evolved out of many mergers. The First Wayne National Bank, by 1931, had combined ten important banking institutions. As a third feature, group banking appeared, particularly in the form of two holding companies— The Detroit Bankers and the Guardian Detroit Union Groups. These two holding companies controlled 87 per cent of the banking resources of the city by the end of 1929. These structural changes appeared to increase both the efficiency and the strength of Detroit banking facilities. Later experiences, however, indicated that home-city branch banking and group banking, even under national charters, did not guarantee bank solvency.

Like banks elsewhere, the Detroit institutions obtained funds from their stockholders, from depositiors, and from funds borrowed from other institutions. A comparison of the amount of stockholders' funds in Detroit banks with that contributed to capital stock of other banks belonging to the federal reserve system indicated that Detroit bank owners did not provide an adequate margin of safety for depositors. As has been inferred, total deposits in Detroit banks grew rapidly, but time deposits tended to increase relatively more rapidly than demand accounts. Bankers' balances with Detroit banks were never large. Evidently this city has not been a great financial center. During the period studied, Detroit banks were not obliged to borrow much from the Federal Reserve Bank, excepting in times of financial emergency. The banks usually held a relatively small amount of loans and discounts which were eligible for borrowing from the reserve institution. In 1924, for example, this amount was a6.i per cent of total loans and discounts; by 1931 it had declined to 5.1 per cent. To compensate for this deficiency, however, the banks held relatively large amounts of United States Government securities.

Detroit banks have carried an unusually large amount of real estate loans. The percentage of such loans to total loans was higher in Detroit than in any of the other cities studied excepting Cleveland. This fact explains in part why banks in these two cities have been in desperate condition. Interesting too is the fact that automobile concerns have borrowed relatively little from Detroit banks, automobile loans constituting only 2.9 per cent of the total in January 1929. Due to branch banking, the average bank loan in Detroit has been small. An analysis of the bond accounts of the banks shows that large investments were made in marketable government securities but that the other bond investments were not particularly liquid. Purchases of acceptances and commercial paper were made only occasionally and then in small amounts.

Finally, a few words regarding Detroit bank policy will provide a useful conclusion. Professor Woodworth says (page 199) "For reasons associated largely with the dominance of the automobile industry, the risks of bank operation in Detroit are comparatively high. These reasons are: (1) the rapid growth of the city, (2) its lack of industrial diversification, and (3) its extremely wide industrial fluctuations." In the face of these risks, an analysis of loans and investments indicate the following outstanding facts: a smaller percentage of Detroit bank funds was placed in investments than in other leading cities; commercial loans have shown a declining proportion over a period of years; real estate loans have been relatively heavy; bond investments have included a large proportion of United States Government securities; and the other bonds held as investments have included large amounts of state and municipal bonds which have not been especially marketable. On the bases indicated, Detroit banks had established a record for safety and solvency. More recently, however, the great risks of bank operation and the unusual loan and investment policies have not been able to weather the storm of prolonged industrial depression. Every student of banking history and policy will benefit from reading this study of the Detroit money market. The comprehensive evidence, presented and analyzed in a practical manner, will be valuable in providing plans and suggestions for banking reform.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

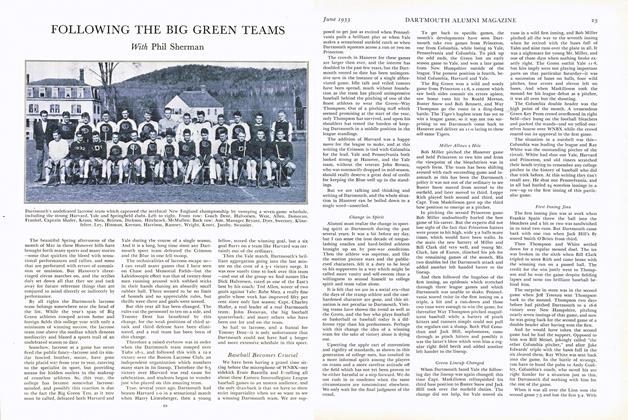

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

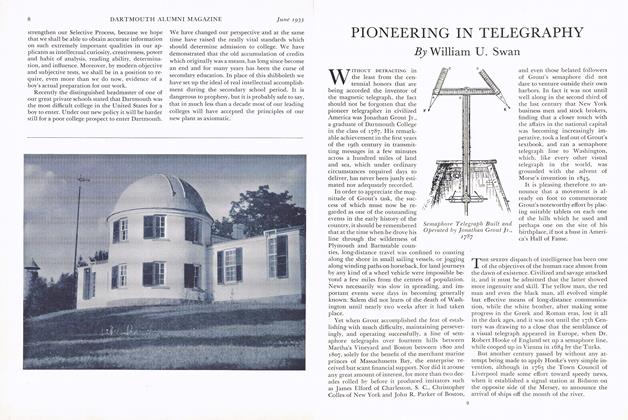

ArticlePIONEERING IN TELEGRAPHY

June 1933 By William U. Swan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of IQ9 1

June 1933 By Jack R. Warwick -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Convene

June 1933

R. V. Leffler

Books

-

Books

BooksTHEATRES AND AUDITORIUMS

JUNE 1965 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksLION AMONG ROSES: A MEMOIR OF FINLAND.

APRIL 1965 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksJOYS AND SORROWS: REFLECTIONS

JULY 1970 By JON H. APPLETON -

Books

BooksTHE HISTORY OF ROME.

JUNE 1959 By NORMAN A. DOENGES -

Books

BooksCONCERNING JUVENILE DELINQUENCY

January 1943 By R. P. Holben -

Books

BooksFacing the Great Issues

MARCH 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38