The President's Address in Opening Dartmouth's 164th Year

TODAY I WISH to discuss the significance of some of the changes of modern life in relation to that form of self-development and self-mastery which we call education. The period offers unprecedented opportunities for leadership but it demands mental conditioning and capacity for moral resistance in like degree. If the processes of selection for admission to college could be made more omnisciently accurate than they can be made, I should urge that Dartmouth in these critical days specify strength as its first requirement,—strength of character, strength of mind, strength of conviction, strength of purpose. The weakling and the man who demands softness and self-indulgence from life are a greater menace to the world's recovery than are all the existent destructive forces.

Education must demand that intelligence be supplemented by positiveness and forcefulness. Education must recognize the existing facts of the mutuality of life. Education must emphasize the fact that cooperative effort of the intellectually enlightened is necessary to overcome the inertia of mass indifference to lessons of the past or to possibilities of the future.

Frequently during the last decade it has not been plain what words would be appropriate or useful at a college opening. The undergraduate of that period, keenly observant of contemporary phenomena, not unnaturally has assumed this to be life. When his shrewd and calculating eye has been cast outside the college, he has seen little to invoke effort or to impose sense of obligation. It has required rather more of evangelical fervor and persuasion than it has been within the power of the college to exercise, to argue convincingly for consideration of the merits of plain living and high thinking against the background of the nation's carnival exhilaration.

Predominantly, the people's credo has seemed to be that the comforts and luxuries of economic plenty could be secured without self-discipline or, at most, more than moderate effort. Adroitness of mind and a nimble wit not only had come to seem an adequate substitute for such qualities but frequently they seemed of superior efficacy in establishing one's self as of consequence among one's fellows. Stability of character, soundness of judgment, and habits of reflective thinking were assumed among many men to be attributes of unimaginative minds. Only such, it was held, would be willing to accept the self-denying training necessary for cultivation of those qualities. Patronizing indulgence was given to those who argued that the mind was too valuable a possession to be allowed to lie fallow; or that depth of personality was of more consequence than superficial geniality; or that acceptance of a training regimen was necessary for accomplishment, physical or intellectual; or that command of knowledge, flexibility of mind, and adaptability of disposition must be assiduously cultivated to meet conditions in a world inevitably subject to constant and often sudden change. Colleges were taken to task for being impractical which undertook to cultivate in their men the art of being rather than exclusively to develop the science of doing. The magnitude of an accomplishment came to be more important, in winning public acclaim, than was its quality. Admiration was given to success regardless of its worth.

It is the natural inclination of the undergraduate to interpret realism simply as consciousness of the present. He is necessarily without experience to have anything except vague apprehension about the future,—what his responsibilities will be, wherein he will find his greatest satisfactions, towards what his aspirations will lead him. Only by supposition can he understand the great solicitude of the college that its influence shall enhance the strength of the manhood into which he is going, rather than simply be pleasing to the adolescence from which he is emerging.

It is in invitation to members of the college to consider its concern at this point that on an occasion such as this attempt is made to state the scope of realism and to define some of the problems with which the college must concern itself in behalf of what will be lifelong interests of men now undergraduates. What shall the college say today of a world whose affairs are as confused as ours are? What conditions are developing, adjustments to which are necessary to the welfare of the generation now enrolled within our colleges? What qualities stimulated and developed in the men of this undergraduate group will most definitely promise solutions of difficulties in which their elders have become inextricably involved?

In the beginning it is to be noted that for youth change brings enlarged opportunity. A radical transformation in the pattern of life is bewildering and in many cases tragically unfair to those who have won established position and security through accepting the existing code in good faith and operating under it with due sense of public responsibility. But for youth, on life's threshold, there is a challenge and a stimulus in the possibilities offered by a radical change in conditions and the opportunity to file entries on even terms with any in competition for the rewards of life. Furthermore, the evidence of history is too convincing to be disregarded that for individuals and for peoples strength and capability develop disproportionately under conditions of hardship and struggle as compared with times of ease and plenty. Maintenance of the status quo or of conditions of economic surplus may insure comfort and peace of mind but under the inscrutable laws of life completer realization of human capability grows out of economic scarcity and out of conditions attended with grave problems and baffling difficulties. This is the significance of the occasional editorial query in this country and abroad as to where the great leaders of the future are being bred amid the difficulties of the present day. It has been repeatedly stated that the world's greatest leaders have been developed in times of crisis. Whence these shall now arise is a pertinent query for consideration in a carefully selected group such as is a college membership like this gathered here.

In consideration of society's distress at the present time there are two highly dangerous attitudes of thought operative which are antagonistic to all for which true education ought to stand. One holds that nothing can be done to save civilization while the other fails to recognize that civilization is endangered and cannot be protected except by thoughtful effort. The devotees of the former and less important of these schools weakly accept a cult of defeatism or indulge themselves in an irresponsible cynicism. These are the traitors and slackers of society, sabotaging the efforts for rehabilitation of our social structures by men more courageous and with deeper sense of obligation than they possess. The easiest escape from any difficult situation is to quit and yet, to the shame of intellectualism, this is the course chosen by some who claim its name. President Roosevelt used to tell a story of how a captain of an ocean liner quelled a panic and saved his ship in time of a crisis which was being intensified to the point of inevitable tragedy by a hysterical passenger screaming, "Nothing can save us. We are doomed." With but an instant in which to act, after vain expostulation, the captain seized the prophet of calamity and threw him overboard, shocking the frightened passengers back to reason and saving hundreds by the sacrifice of one. The method has its merits!

Pessimism which recognizes danger and shouts warning in regard to it may well be a desirable effect of education but pessimism which accepts hopelessness is no more a part of intelligence than it is of courage. It is a part of the wearisome self-consciousness of a generation which attaches exaggerated importance to all of its own emotions and holds its experiences to be more difficult and more painful and more tragic than anything the world has ever known. The origins of such pessimism are in lack of historical perspective of the past and in lack of faith for the future. Education, even if it can offer little to support a theory of the inevitability of progress, cannot in justice to its own self-respect tolerate the belief that progress is unattainable.

The second school of thought—rather it should be said that this group is existent because of lack of thought—is conscious of no crisis and recognizes no hazard in insistence upon satisfaction of its own ephemeral interests. Typical of this spirit and conspicuous for the moment is the present attitude of sponsors for ever increasing gratuities to World War veterans. It is folly to suppose that all of those arguing for these measures are wholly selfish or are consciously willing to ruin the country for their own ephemeral advantage. The charitable explanation must be one of complete lack of understanding on their part of the gravity of the world crisis or of how intolerably heavy an addition they are attempting to load as a last straw upon civilization's back. In passing, however, the further comment should be made that a like charitable explanation cannot be made of the attitude of representatives and senators who for political purposes encourage this demand or endorse it or seek political favor by promising to support it.

In current discussions as to this and kindred questions some light might be derived from reading history. For instance, there is Gibbon's description of the destructive effect upon the Empire of the machinations of the Praetorian Guards in Rome. These legionnaires exploited their original popularity and reputation for valor until they destroyed every vestige of respect for themselves and contributed largely to the downfall of the Roman government from its high place above all the nations of the earth.

The Praetorian Guard was originally recruited to safeguard home affairs and was selected from men distinguished for valor in foreign service and for their keen sense of patriotism. For a time these legions were the pride of Rome. Insidiously, however, a class consciousness of their potential power sprang up among the legions and an acquisitiveness for preferential treatment which led to demand after demand upon the state for gratuities. Cultivating their power in deciding elections, they secured what they sought in each successive demand. Gradually their appetite for extravagant subsidy became so voracious that they turned to the use of force and assassination, overthrew the government, and called for competitive bids for their favor, promising to make him emperor who would distribute among them the largest money grants. Going from one bidder to another and holding the election open until the highest possible offer had been secured, sale of the position was made to a member of the Roman senate who eventually made payment from the public treasury at a cost of millions to the state.

Meanwhile, typical of the same spirit but more far-reaching are the implications of many of our present-day political theories. At the close of the World War expression of the idealistic aspiration to make the world safe for democracy was met in rebuttal by the qualifying reservation that democracy ought first to be made safe for the world. At the time this latter statement was made no great emphasis was placed upon it except among a few. Today, however, it expresses the most profound truth applicable to discussion of the world's welfare. The greatest handicap to solving the dilemmas in which we are involved is the nature of our political democracy. In a world where events and crises develop with lightning speed, the incapacity of our form of government to act with any promptness may at any time become a fatal weakness. Democracy's clumsiness, its unsatisfactory level of intelligence, and its jealousy of any quality above the average make overwhelmingly difficult any discriminating choice of leaders. The delegation of authority and power is too infrequently given to those most qualified to exercise these by characteristics of ability, forcefulness, and concern for a broad public welfare. It is no tenable theory of democracy that in accepting obligation to give justice to all men it shall likewise give the same rights to all men regardless of merit.

Ten years ago at a college opening I asserted that there was such a thing as an aristocracy of brains made up of men intellectually alert and intellectually eager to whom increasingly the opportunities of higher education ought to be restricted if democracy were to become a quality product rather than simply a quantity one. Later, in reply to the vehement criticism of the assertion that there could be any desirability in an aristocracy of brains, I stated my conviction that the ascent of human beings from primitive man was to be ascribed to the primacy ultimately secured by men of superior mental capacity in critical junctures of human affairs. Beyond this, I stated my further conviction that the most democratic procedure conceivable was the recognition and acceptance from generation to generation of such an aristocracy based on contemporaneous ability and free from the artificial prestige of birth or the mere affluence of wealth or the fortuitous possession of instruments of force,—an aristocracy determined solely by that which distinguishes man from all other living beings, the human mind. Some influence was going to be dominant in the affairs of mankind, I argued, and if it were not to be the qualities of men of superior intellect, what else could be as advantageous?

Now, I am prepared to go much further and to contend that the most serious danger threatening civilization today is the rapid development of a perverted sense of democracy at home and abroad which encourages public opinion not only to accept but to idealize mediocrity and which allows public opinion to be ostentatiously arrogant in its indifference to intelligence and antagonistic towards any process of thought in its leaders which rises above its own average mental capacity. The fallacies of interpretation of statements that all men are created equal have become embodied in our thinking until we have ceased to admire either the man richly endowed who has capitalized all available facilities to make himself competent in high degree or the man who has broken down the confining walls of limited opportunity and has emerged from his environment mentally and spiritually capable of great works. Under the spurious standards of our present-day democracy enthusiasm is reserved largely for the common man who remains common rather than for the common man who makes himself uncommon. Anything which sets a man apart from the usual run of men becomes a liability rather than an asset so far as being accepted for leadership goes, to say nothing of being chosen for it. Originally, our glorification of the average man was because of his oft-proven capacity to rise above the average. This is no longer so. Public confidence and popular applause are given most largely not to those who are capable of raising the level upon which we live and think and act but to those who stoop to the average and pander to the common. It is no less keen an observer than the distinguished editor of the HibbertJournal who says, after months of close and friendly observation of America, that the one thing which our democracy "consistently abhors" is discipline. He states that to secure the submission of the Anglo-Saxon to discipline "you must call it by some other name" and his choice is "education." The NewYork Times, commenting upon this editorially, adds sapiently, "If that substitution is made, education must mean discipline, for democracy without collective self-discipline is chaos."

My argument is not against the principle of democracy, in which I firmly believe, but it is against an undisciplined and therefore irresponsible form of democracy. It is against that prostitution of the principle which assumes that privileges and rights should be distributed among all men without any demand upon mankind that responsibility be accepted as widely as opportunities are conferred. A theory of democracy accepted as desirable for all others except ourselves but from which we as individuals feel free to set ourselves apart has little vitality to perpetuate itself as a social or political force and has little justification in trying to perpetuate itself. John Purroy Mitchel, New York City's capable reform mayor, used to say in contemplation of his heartbreaking defeat after four years of the best government the city had ever known that the people of that city did not want even-handed justice, since this would interfere with the existence of special privilege which might otherwise be available to them for personal utilization, if needed. Few of us, unfortunately, can claim complete immunity from this attitude. In other words, all theory to the contrary, the spirit of democracy is not a natural instinct for mankind. In so far as it becomes existent, it is an acquired characteristic and for its acquisition individual and collective self-discipline is necessary. Herein lies a vital function of education,—to cultivate a willingness for self-discipline. Left to itself, democracy breeds down to a standard of mediocrity and to a standard of thought intolerant toward those possessed of attributes above the average or capable of accomplishment beyond the ordinary man.

Cooperation for the common good under intelligent leadership is the essence of social and political democracy. Yet how painstakingly do we strive for intelligent leadership or how complete cooperation can we assume in regard to the realization of the objectives to the merits of which we may have subscribed? Considering the principle of cooperation for a moment, how deep will be the thoughtful analysis of the issues in the present political campaign before our votes are cast on election day? Does any believe that the Eighteenth Amendment would have so completely failed of its purpose if all of those who voted for it originally or those who have continued to argue for its maintenance had cooperated personally for upholding and vindicating it? In the discussion of recent months in regard to balancing the national budget, upon the necessity of which there has been common agreement, how evident has the spirit of cooperation been to waive personal or provincial interest for the sake of securing a scientific tax law with an equitable distribution of its imposts? On any project of civic betterment, even among those who assent enthusiastically to its desirability, how complete a cooperation can be counted upon for overcoming the inertia necessary to its accomplishment?

Parenthetically, within our own academic world few would willingly forego the personal satisfaction to themselves in having high reputation attached to the college with which they have become associated.

Nevertheless, Dartmouth would become an exception among all institutions of its kind if it could expect complete cooperation from its undergraduates to enhance this reputation by scholarly endeavor and by responsible personal conduct.

Oliver Wendell Holmes in a preface to the "Autocrat of the Breakfast Table" wrote a parable which still remains illustrative of the reason for failure of many an effort dependent for success upon cooperation. He said:

"Once on a time, a notion was started, that if all the people in the world would shout at once, it might be heard in the moon. So the projectors agreed it should be done in just ten years. Some thousand shiploads of chronometers were distributed to the selectmen and other great folks of all the different nations. For a year beforehand, nothing was talked about but the awful noise that was to be made on the great occasion. When the time came, everybody had their ears so wide open, to hear the universal ejaculation of Boo.—the word agreed upon,—that nobody spoke except a deaf man in one of the Fejee Islands and a woman in Pekin, so that the world was never so still since the creation."

Still, it is to be noted, lack of cooperation is not due entirely to lack of will in these days. Many of the conditions of modern life make it practically impossible to cooperate. The world today is suffering from uncoordinated thought. Never was there more brilliant thinking and never was thinking more productive of accomplishment but the thinking and the accomplishment of one group are entirely detached from the thinking and accomplishment of another. The inevitable assumption for all except philosophers comes to be that there is no relationship among these groups. A man's scholarship or another man's industrial leadership or still another man's financial genius may be outstanding in his field and yet be entirely without discriminating judgment in regard to public policies or concerning the responsibilities of citizenship. The era of specialization has developed so rapidly that we are still without consciousness of the sacrifices which it has entailed. Specialization has largely destroyed the supply of men of broad talents formerly available for the organization of life for its greatest common advantage to all men. Our men capable of high potential thinking and of great works are being conscripted for service within highly specialized groups. Consequently, when under demands of the common welfare the diverse interests of these groups have to be harmonized, when social compromises and adjustments are imperative, or when processes of government need to be made of maximum effectiveness, we have no sufficient number of competent minds to meet our needs. There are but few whose experience has given them any contemplation of life in its fullness or whose contacts with life have been broad enough to qualify them for undertaking these responsibilities.

I have left this question of leadership, with which education is particularly concerned, until the last. I have repeatedly stated through past years that intelligent leadership could only be operative through the support of an intelligent constituency. Thus, a college which could supply to the body politic a citizenry eager to select, follow, and support capable leadership would render service of incomparable value. Moreover, the probability is that leaders themselves would emerge from such a group rather more frequently than from any other.

In the United States today intelligent consideration of the question of political leadership cannot be given without consideration likewise of the rapidity with which we are being transformed from a republic, administered by highly capable citizens, to a pure democracy, intolerant of independence of thought and antagonistic to independence of action in its representatives. The inevitable trend of pure democracy in practice is toward concentration of power in aggressive blocs seeking special privileges and thus in the eventual establishment of an oligarchy, heedless of common welfare. Perhaps the decline started with changing the status of the electoral college to a rubber stamp of popular will instead of continuing it in accordance with original plan as a responsible group with power delegated to it to take independent action. At any rate the process has been accelerated out of hand in the last three decades. Particularly in the transfer of power for electing United States senators from the state legislatures to the whole electorates of the respective states and then in the replacement of the convention system by the direct primary, the tendency is plain of subordinating to popular passion or temporary caprice the independence of thought and action possible to the people's representatives.

I realize the reply which will be made by those who say that the palliative for the ills of democracy is more democracy,—the assertion of the danger of corruption in small groups. In reply to this I should say that in the light of results it is the part of intelligence now at least to recognize that there was better chance of safeguarding such groups from corruption than there has proved to be of avoiding the demoralizing weaknesses of the substitutes which we adopted. We have abolished processes capable of fine discrimination, as well as of base manipulation, and in confession rather of our indisposition than of our incapacity to control these processes we have adopted practices no less susceptible to misuse and totally incapable of anything except the most superficial discrimination. The result has been inevitably to produce a public policy based on mass production of sentiment in the formation of which propaganda is far more effective than reason and the demagogue is more influential than the philosopher.

I am fully aware that many of these assertions are more definitely in the controversial field than ordinarily is appropriate to an academic address but I believe that circumstances of the time demand consideration of them. It is meet in behalf of those who idealize the theory of democracy, as well as in behalf of all others, that our practices of democracy be reexamined, reappraised, and re-formed, eliminating the grave hazards of weakness and developing the attributes of power.

The number of those in this country who have had benefit of formal education, supplemented by the host of those who without such advantage have like high intelligence and good will, is sufficiently great to assert itself effectively in the creation of a new spirit towards government and in the establishment of a new social order. If the cult of the commonplace and the vogue of the average thrust aside or submerge the ideals and aspirations cherished by individuals, as for instance in the case of many a man on graduation from college, what reason exists why there should not be a mobilization of such men for cooperative action? Is the proposal as quixotic as it may sound? Is education impotent to help in salvaging civilization? Are the educated classes, as Gerald Stanley Lee suggests, incapable of any fine frenzy for the establishment of their ideals and are they simply what he calls "yearners"? I think not.

World conditions and conditions among our own people are alike a challenge to intelligence. The struggle may be a long one and it inevitably will be a difficult one. Meanwhile, what an opportunity such a critical period offers to men creative in their imagination, high in their principle, and disciplined, in their thought! Never was a generation more to be envied, if only it will impose upon itself the requirement to develop itself to the limit of its capability. No counsel more relevant to the time can be given to youth today than the injunction that Paul placed upon his young and personable disciple, Timothy, "Thou, therefore, endure hardness."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1922

October 1932 By Francis H. Horan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1932 By Prof.Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

October 1932 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

October 1932 By Arthur E. Mcclary -

Article

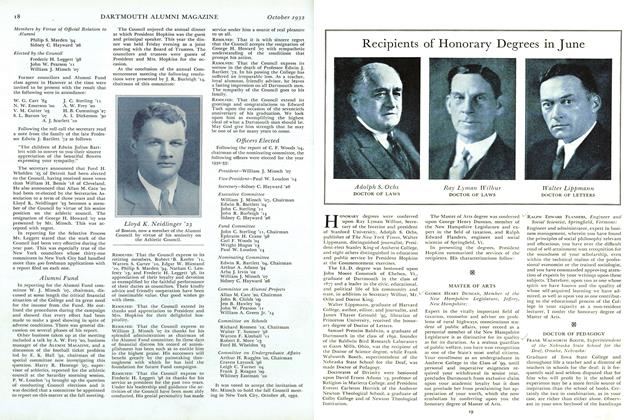

ArticleRecipients of Honorary Degrees in June

October 1932