I HAVE BEEN asked by the Editorial Board of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE to conduct a column on Books. The intent of the editors, I take it, is that I should draw on the collective resources and expert knowledge of the Dartmouth Faculty for suggestions as to books which may be of assistance to interested alumni. It is hoped that this will prove a real boon to those desirous of keeping in touch with the best that is thought and written in the field of their particular interests as well as in the broader field of general culture. It is obviously too difficult a task for any one man to render this assistance effectively. No one is more aware of this than the writer. Therefore, for this and other equally desirable reasons, I shall consult from time to time different members of the faculty as to their judgment of profitable books worthy of inclusion in this column.

Issuing a short manifesto of my own as a prospective reviewer, I will not plague the reader by enunciating at length the principles which will guide me in my selections. Most of them will be revealed in the issues to come. All I can do at this juncture is to promise to be honest and discriminating in my recommendations, and this is no small promise in this age of easy recommendations. I shall try not to over-praise booksparticularly every book that I may chance to read. Few are the books that can stand over-praise. Yet the modern reviewer is tempted constantly in that direction. If publishers send any books for review in this column I promise to laud only those deserving it. The rest I shall damn by discreet silence, or, at most, by the faintest sort of praise. It was Dr. Johnson who said of someone that "he speaks truly, but feebly." I also will now and then speak feebly, but I hope truly. This means that I must beware of adjectives, for they are the very deuce in contemporary reviewing.

I shall keep a constructive purpose in view and avoid making my reviews too critical. A definite scale of values is implied in this statement, but for the time being I shall keep it very far back in my mind.

I shall not attempt to give the latest thing in books. My concern is with the excellent. Older and later works will be recommended when occasion warrants. Needless to say my approval or disapproval will not mean necessarily that I am in agreement with the ideas expressed by the respective authors. Equally unnecessary is it for me to emphasize the importance of books in the good life. College men know their value although they may lack time to read many of them. Moreover, they are aware that college education is just the beginning of what L. P. Jacks calls "the education of the whole man." (In a book of that title—recommended mildly.) We are coming to realize more and more that education is a life task. That is why adult education is stressed so much today. And in so far as adult education goes experience and books are the best teachers. Carlyle was right in this connection in stating that the best university is the university of books. I wonder if the dour old Titan would say the same thing after tasting some of our modern product. But I must refrain from pursuing this line of thought or else my column will become an essay on the delights and tortures of reading. Yet I cannot help quoting Gandhi's prison recommendation of books. It is found in his autobiography (recommended). "In this world," he says, "good books make up for the absence of good companions. Therefore, all Indians who want to live happily in jail should accustom themselves to reading good books." But to return to my sheep as the old adage goes. The books I recommend in this issue are the following:

1. Preface to Morals: Walter Lippmann. Macmillan and Co., 1929.

2. BreakDown: Robert Briffault. Brentano, N. Y., 1932.

3. The Rise of American Civilization: Beard and Beard. Macmillan and Co., 1930. One volume edition.

4. The Epic of America: J. Truslow Adams. Little, Brown and Co., 1931.

5. Main Currents in American Thought: V. L. Parrington, 3 volumes. Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1927 and 1930.

6. A Literary History of the AmericanPeople: Charles Angoff. Alfred A. Knopf. Two volumes of a prospective 4 volume study, 1931.

7. The Liberation of American Literature: V. F. Calverton. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1932 (just publishedprice $3.75).

The first two on the list—Lippmann's and Briffault's—have enough in common to justify me in grouping them together. Both undertake to show how the traditional, ideas and ideals and fictions associated historically with Western Civilization have broken down, and how, as a consequence, modern men and women are in a state oF mental and spiritual chaos. Lippmann's central idea is that the modern mind can no longer find a home in the old ethical and religious beliefs and conceptions which in the course of centuries had become integral parts of Western culture. They no longer have any power to command our loyalties. Their authority has been undermined and their power challenged and shattered. The acids of modernity have eaten away the supporting pillars of the ancestral order. The growth and spread of scientific knowledge and the ever-increasing complexity of an urbanized, mechanized civilization have combined to make it impossible for modern men to find guidance and inspiration in the body of ideas which nourished our forefathers. The constructive part of the book is an attempt to discover in germ at least some helpful principles to guide us in the tantalizing task of ordering our lives and our institutions with some measure of mastery and fruitfulness. The insights of high religion and the disinterested, objective modes of thinking characteristic of science—physical and social—are canvassed very acutely to see what they can offer us as aids in formulating the beginnings of an individual and an institutional morality that will be workable in the complex world of the twentieth century. On the whole, one of Lippmann's best books.

Another older work of his which we can recommend highly is "Public Opinion." This is still one of the most acute and penetrating analyses of public opinion and its nature, mechanisms, formation, limitations and operations. Well worth reading.

In passing from Lippmann to Briffault, we pass from one of the sanest exponents of American liberalism to one of the ablest and most provocative of English intellectual radicals. With some justification he may be called a sort of anthropological Karl Marx. He has a number of books to his credit, a little uneven and varying in quality. His best are "Rational Evolution"— a spirited and stylistically florid treatment of the achievements and possiibilities of rational thought when guided by a cumulative and verifiable body of data as well as a pungent but convincing historical elucidation of the stultifying effects of custom-thought and power-thought; "The Mothers"—a bosky, scholarly work in three volumes, containing an enormous quantity of anthropological material and essential to students of anthropology and sociology—and finally, "Break Down."

This book is important in itself, but it may be more significant in its implications and disturbing suggestions. Its main feature is a downright expression of a radical, revolutionary point of view. It is calculated to provide damaging ammunition in the form of ideas to a host of revolutionary thinkers. His thesis is simple but terribly upsetting and revealing. Western civilization, he argues, is a traditional civilization. Its basis is the authority of tradition, and its purpose is the perpetuation of the interests and power of the dominant classes. It does not subserve the interests of humanity. But, as a result of the advance of science and the growth of technology and the cumulative rebelliousness of the exploited classes, its authority is being undermined. The myths or dominant ideas on which it depended for its intellectual support have ceased to work. They no longer enlist the loyalties of men (the same idea as in Freud's "The Death of an Illusion," recommended mildly). The outcome is the breakdown of our civilization, economically, politically, morally and spiritually. It is breaking down from within. And nothing can save it. Briffault sheds no tears over the collapse; on the contrary he is exultant. What are we to do then? The answer is desist from our futile, liberal efforts to save this collapsing traditional and predatory civilization, and with courage and intelligence undertake the task of introducing planfulness into our social order and thus build up our culture on the basis of reason and justice. The argument and the animating spirit of the book are frankly revolutionary. My guess is that the book is likely to affect the thinking of a goodly number of liberals and radicals, and, undoubtedly, will be used by them in a similar manner to the use made in the past of Veblen's "Theory of the Leisure Class" (recommended).

Progressing from these challenging and disconcerting volumes to the others on my list, we go from the more general and discursive to the historical and the particular. In one form or another they deal with the series of inner and outer changes which constitute American history in the last 300 years. These mutations are similar in character to those which called into action the minds of Lippmann and Briffault. However, the emphasis and the objective are different—except in the case of Calverton. The last section of his book is in line with Briffault and his general outlook is the same.

Two of the books on my list are among the popular books of recent vintage. Of the two, Adams' "The Epic of America" has a more popular appeal, but I think there is more solid substance to the "Rise of American Civilization." In line with a great deal of modern historical writing, both stress the influence of the frontier and economic forces on American life and thought. Adams, in a general way, dramatises history a little more than the Beards', or, one could say that the propulsive dream back of American history is dramatised by the one and the confused reality by the other. Yet, both are concerned with the same significant changes and the same disturbing consequences. And both are worth studying.

The remaining numbers on the list are brilliant and illuminating studies of American social and literary history and their interactive relations. From the point of view of esthetic criticism the purest of the three is Angoff's. So far, however, only two of the contemplated four volumes have been published. These two have some sterling and, unfortunately, some exasperating features. Their chief weakness arises out of the author's, excessively belletristic judgments of the literature he is interpreting. After a while they become tiresome, and, I venture to suggest, now and then trivial and unfair. In themselves I would agree with most of his pronouncements. But sometimes they are empty and impertinent. In many instances they are penetrating, although often gratuitous and irrelevant. And irrelevant acuteness can be irritating. One of the excellent features of the volumes is their apposite and original quotations and selections. His interpretations are likewise illuminating in many cases.

Parrington's three volume study—the third posthumous and unfinished—l make bold to say should grace the library of every cultured American. He is a hard hitter who has the knack of getting home his blows. His interpretations of the backgrounds and the foregrounds of American literature are splendid in both logic and discernment. He reveals a lucid, discriminating mind in his appraisal of the significant ideas and works and personalities he is discussing. His work constitutes a stimulating attempt at a kind of social criticism of American ideas and literature which has been attempted only too seldom by our critics. The limitations of Parrington's liberal, Jeffersonian viewpoint are visible more in the third than in the first two volumes. Unmodified as it was, it was palpably too limited to do justice to the complexities of modern American civilization.

Calverton's "The Liberation of American Literature" (just published) may with some relevancy be regarded as an effort by a radical critic to overcome this limitation of Parrington as well as to provide a corrective to the unashamed esthetic emphasis of Angoff. Here again we have a critical volume dealing with the social backgrounds and root conflicts of American literature, together with the body of ideas and complex of class interests out of which that literature arose, and which in one form or another it either reflects or expresses, or clarifies and crystallizes. The differences between it and the volumes of Parrington are due mainly to the proletarian emphasis of Calverton. In essentials the book is a Marxian interpretation of American life and thought, and it can be recommended for that reason besides its intrinsic excellence. Here in America we have so few first-rate proletarian, Marxian critics of any scholarly consequence that a serious attempt to evaluate American literature from that viewpoint is, to say the least, interesting. And Calverton, on the whole, is an able representative of the proletarian school of critics. His earlier work on "The Newer Spirit" disclosed the major lines along which his thinking was to develop. However, that book had serious limitations. He had for one thing not thought through his position and his illustrative material was too scanty and dubious to support his thesis. Other books by him which I have read are open to similar criticisms. All in all the present work is his best. He has more pertinent material at his command, and he handles what he has of it better. Unfortunately, he is still using secondary sources and material to a large extent, but then others do that even more unashamedly. He at least reacts to his material in his own vigorous way. It is all grist to his Marxian mill and he knows what he wants to do with it.

His principal point—and it is this that gives meaning to the title of the book- is that American literature until late in the nineteenth century was enslaved by the cultural dependence of American writers on British culture, and on the petty, bourgeois spirit and ideals and inhibitions derived from that culture. Its essential characteristics, therefore, were those associated with the colonial complex of dependence and the narrow, Puritanic ideas and material ideals and conflicts of the lower middle classes. The liberation is a growing independence in form, matter, spirit and outlook on the part of Amercan writers. The forces making for liberation came out of the frontier and the class conflicts generated by the growth of American industrialism.

The latter part of the book is not so satisfactory. I say this not so much because I object to the author's proletarian and revolutionary point of view, but rather because he seems to me to have forsaken in it the task of the critic and the interpreter and has become the propagandist a little too much to suit my taste. This failure to finish his job as a critic accounts for his exaggerated laudation of some of our modern proletarian novelists and critics, especially Dos Passos and Michael Gold. He overrates their work in my candid opinion.

Moreover, if what he writes is sound, American literature is faced with one more struggle for liberation. It must be emancipated from proletarian motivation and revolutionary mentality as much as from the enchaining limitations of the colonial complex and the petty, bourgeois philosophy of life. Then it will become really of age and chainless. Then it will be free to proceed confidently with its proper task of giving American life a new freedom and joyousness and American thought and culture a new beauty and excellence.

To bring my introductory column to a close, I repeat once more these are on the whole excellent books and well worth reading. Whatever may be said in criticism of them (and a lot more may be said), it can be said at any rate of their authors that they are not haberdashers of petty ideas or purveyors of pompous platitudes. They are intellectually honest and in divers manners have tried to interpret the complex world in which we have to live and how it became what is has become.

I am confident that any Dartmouth man reading these books with care will be rewarded generously for his pleasant labor, and that is something in these days of chronic unemployment and uncertain rewards.

(Either through this column or by letter the reviewer in so far as he possiblycan will be glad to answer inquiriesabout books which any uiterested alumnus may care to send in to him.)

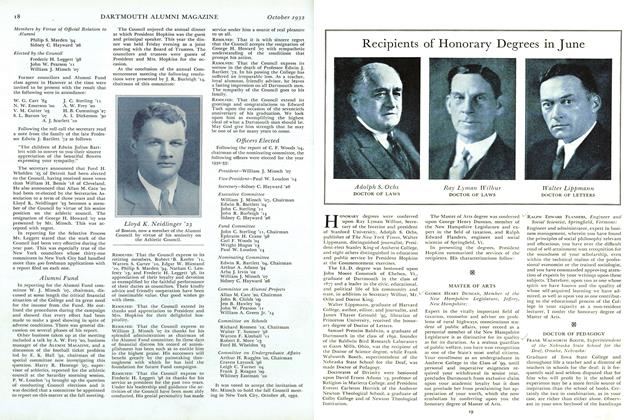

BOOKS FOR DARTMOUTH MENwill be recommended monthly inthese pages by Professor Bowen. Hehas had wide experience as reviewerand critic; his "book-a-day" readingand his discriminating literary tastesoffer a pleasant opportunity to alumnito acquire knowledge and wisdomunder his guidance. Mr. Bowen willpresent his suggestions, and those offaculty associates, on a variety of literary forms—whether technical, cultural, fiction, biography, drama, murder-mystery-detective. As he requests,any questions or comment relating tohis column may be addressed to him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCHANGE IS OPPORTUNITY

October 1932 By Ernest Martin Hhopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1922

October 1932 By Francis H. Horan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1932 By Prof.Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

October 1932 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

October 1932 By Arthur E. Mcclary -

Article

ArticleRecipients of Honorary Degrees in June

October 1932

Rees Higgs Bowen

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

January 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen

Article

-

Article

ArticleFINAL RESULTS IN BASKETBALL AND HOCKEY

April, 1915 -

Article

ArticleGEORGE F. BAKER DONATES $100,000 TO COLLEGE

February 1925 -

Article

ArticleStudent Editors Produce Special Alumni Issue

MAY 1965 -

Article

ArticleDanforth Graduate Fellows

MAY 1971 -

Article

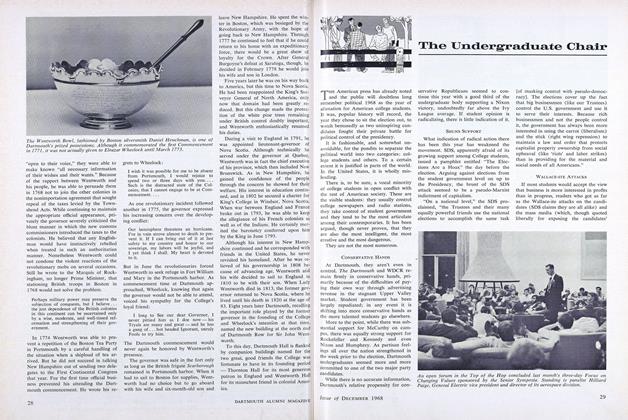

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1968 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleSOCCER

DECEMBER 1968 By JACK DEGANGE