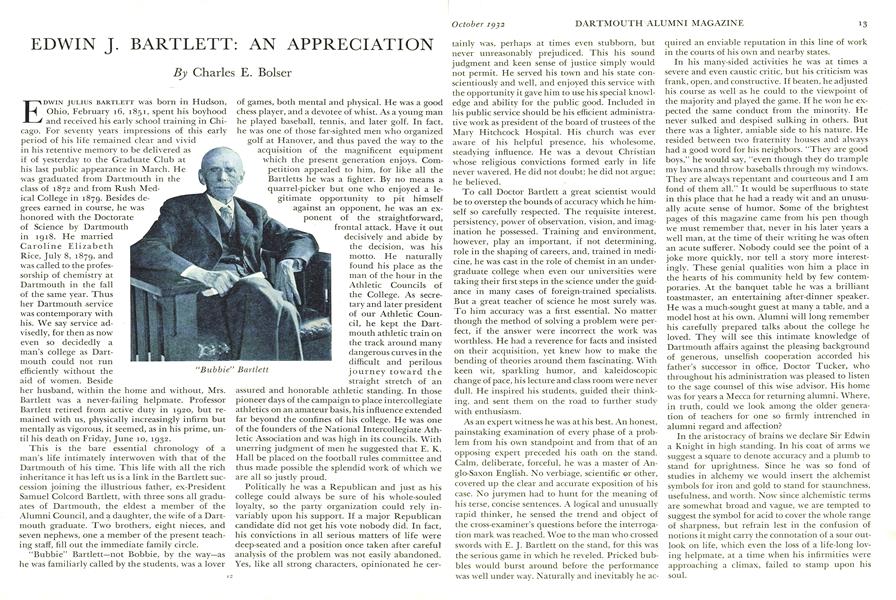

EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT was born in Hudson, Ohio, February 16, 1851, spent his boyhood and received his early school training in Chicago. For seventy years impressions of this early period of his life remained clear and vivid in his retentive memory to be delivered as if of yesterday to the Graduate Club at his last public appearance in March. He was graduated from Dartmouth in the class of 1872 and from Rush Medical College in 1879. Besides degrees earned in course, he was honored with the Doctorate of Science by Dartmouth in 1918. He married Caroline Elizabeth Rice, July 8, 1879, and was called to the professorship of chemistry at Dartmouth in the fall of the same year. Thus her Dartmouth .service was contemporary with his. We say service advisedly, for then as now even so decidedly a man's college as Dartmouth could not run efficiently without the aid of women. Beside her husband, within the home and without, Mrs. Bartlett was a never-failing helpmate. Professor Bartlett retired from active duty in 1920, but remained with us, physically increasingly infirm but mentally as vigorous, it seemed, as in his prime, until his death on Friday, June 10, 1932.

This is the bare essential chronology of a man's life intimately interwoven with that of the Dartmouth of his time. This life with all the rich inheritance it has left us is a link in the Bartlett succession joining the illustrious father, ex-President Samuel Colcord Bartlett, with three sons all graduates of Dartmouth, the eldest a member of the Alumni Council, and a daughter, the wife of a Dartmouth graduate. Two brothers, eight nieces, and seven nephews, one a member of the present teaching staff, fill out the immediate family circle.

"Bubbie" Bartlett—not Bobbie, by the way—as he was familiarly called by the students, was a lover of games, both mental and physical. He was a good chess player, and a devotee of whist. As a young man he played baseball, tennis, and later golf. In fact, he was one of those far-sighted men who organized golf at Hanover, and thus paved the way to the acquisition of the magnificent equipment which the present generation enjoys. Competition appealed to him, for like all the Bartletts he was a fighter. By no means a quarrel-picker but one who enjoyed a legitimate opportunity to pit himself against an opponent, he was an exponent of the straightforward, frontal attack. Have it out decisively and abide by the decision, was his motto. He naturally found his place as the man of the hour in the Athletic Councils of the College. As secretary and later president of our Athletic Council, he kept the Dartmouth athletic train on the track around many dangerous curves in the difficult and perilous journey toward the straight stretch of an assured and honorable athletic standing. In those pioneer days of the campaign to place intercollegiate athletics on an amateur basis, his influence extended far beyond the confines of his college. He was one of the founders of the National Intercollegiate Athletic Association and was high in its councils. With unerring judgment of men he suggested that E. K. Hall be placed on the football rules committee and thus made possible the splendid work of which we are all so justly proud.

Politically he was a Republican and just as his college could always be sure of his whole-souled loyalty, so the party organization could rely invariably upon his support. If a major Republican candidate did not get his vote nobody did. In fact, his convictions in all serious matters of life were deep-seated and a position once taken after careful analysis of the problem was not easily abandoned. Yes, like all strong characters, opinionated he certainly was, perhaps at times even stubborn, but never unreasonably prejudiced. This his sound judgment and keen sense of justice simply would not permit. He served his town and his state conscientiously and well, and enjoyed this service with the opportunity it gave him to use his special knowledge and ability for the public good. Included in his public service should be his efficient administrative work as president of the board of trustees of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital. His church was ever aware of his helpful presence, his wholesome, steadying influence. He was a devout Christian whose religious convictions formed early in life never wavered. He did not doubt; he did not argue; he believed.

To call Doctor Bartlett a great scientist would be to overstep the bounds of accuracy which he himself so carefully respected. The requisite interest, persistency, power of observation, vision, and imagination he possessed. Training and environment, however, play an important, if not determining, role in the shaping of careers, and, trained in medicine, he was cast in the role of chemist in an undergraduate college when even our universities were taking their first steps in the science under the guidance in many cases of foreign-trained specialists. But a great teacher of science he most surely was. To him accuracy was a first essential. No matter though the method of solving a problem were perfect, if the answer were incorrect the work was worthless. He had a reverence for facts and insisted on their acquisition, yet knew how to make the bending of theories around them fascinating. With keen wit, sparkling humor, and kaleidoscopic change of pace, his lecture and class room were never dull. He inspired his students, guided their thinking, and sent them on the road to further study with enthusiasm.

As an expert witness he was at his best. An honest, painstaking examination of every phase of a problem from his own standpoint and from that of an opposing expert preceded his oath on the stand. Calm, deliberate, forceful, he was a master of Anglo-Saxon English. No verbiage, scientific or other, covered up the clear and accurate exposition of his case. No jurymen had to hunt for the meaning of his terse, concise sentences. A logical and unusually rapid thinker, he sensed the trend and object of the cross-examiner's questions before the interrogation mark was reached. Woe to the man who crossed swords with E. J. Bartlett on the stand, for this was the serious game in which he reveled. Pricked bubbles would burst around before the performance was wrell under way. Naturally and inevitably he acquired an enviable reputation in this line of work in the courts of his own and nearby states.

In his many-sided activities he was at times a severe and even caustic critic, but his criticism was frank, open, and constructive. If beaten, he adjusted his course as well as he could to the viewpoint of the majority and played the game. If he won he expected the same conduct from the minority. He never sulked and despised sulking in others. But there was a lighter, amiable side to his nature. He resided between two fraternity houses and always had a good word for his neighbors. "They are good boys," he would say, "even though they do trample my lawns and throw baseballs through my windows. They are always repentant and courteous and I am fond of them all." It would be superfluous to state in this place that he had a ready wit and an unusually acute sense of humor. Some of the brightest pages of this magazine came from his pen though we must remember that, never in his later years a well man, at the time of their writing he was often an acute sufferer. Nobody could see the point of a joke more quickly, nor tell a story more interestingly. These genial qualities won him a place in the hearts of his community held by few contemporaries. At the banquet table he was a brilliant toastmaster, an entertaining after-dinner speaker. He was a much-sought guest at many a table, and a model host at his own. Alumni will long remember his carefully prepared talks about the college he loved. They will see this intimate knowledge of Dartmouth affairs against the pleasing background of generous, unselfish cooperation accorded his father's successor in office, Doctor Tucker, who throughout his administration was pleased to listen to the sage counsel of this wise advisor. His home was for years a Mecca for returning alumni. Where, in truth, could we look among the older generation of teachers for one so firmly intrenched in alumni regard and affection?

In the aristocracy of brains we declare Sir Edwin a Knight in high standing. In his coat of arms we suggest a square to denote accuracy and a plumb to stand for uprightness. Since he was so fond of studies in alchemy we would insert the alchemist symbols for iron and gold to stand for staunchness, usefulness, and worth. Now since alchemistic terms are somewhat broad and vague, we are tempted to suggest the symbol for acid to cover the whole range of sharpness, but refrain lest in the confusion of notions it might carry the connotation of a sour outlook on life, which even the loss of a life-long loving helpmate, at a time when his infirmities were approaching a climax, failed to stamp upon his soul.

"Bubbie" Bartlett

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCHANGE IS OPPORTUNITY

October 1932 By Ernest Martin Hhopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1922

October 1932 By Francis H. Horan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1932 By Prof.Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

October 1932 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

October 1932 By Arthur E. Mcclary