IN ONE of his metaphysical dialogues Giordano Bruno exclaims whimsically that "Ignorance is the most attractive science in the world because it is acquired without labor or pains." The old "awakener of sleeping minds," as he called himself, hit the nail on the head. Hardly anyone will question the attractiveness of the science of ignorance or the soundness of the reason Giordano gives for its universal appeal. The way of knowledge is hard and exacting. And the price we have to pay for wayfaring on that road is a severe one. It demands of its sojourners austerity of life and discipline of mind. Yet the rewards of knowledge are progressively more satisfy- ing than the easy wages of ignorance. This I believe would be the considered confes- sion of all those who have quested after knowledge. During the last few weeks I have experienced anew the rigorous de- mands of the one and the tempting ease of the other. Since my introductory article publishers have sent me an assortment of books on a tantalizing variety of subjects. And when I look at them the truth of Bruno's statement comes home to me with an agonizing clarity. Ignorance is truly easy and attractive while knowledge is hard and forbidding. But in a deeper sense ignorance is dull and uninviting and knowledge is perennially fresh and liberating. I imagine this is the real reason why the ponderous mind of man can never renounce its tortuous search after the values enshrined in knowledge.

Owing to the bewildering variety of the books calling for my attention I must postpone reviewing some of them to a later issue. I do not want this column to degenerate into a hodge-podge of loose comments on unrelated books. I shall choose books from month to month possessing a certain minimum of unity, or at least that can be made to spell some sort of unity. For this reason I am compelled to relegate to future issues books dealing with the present economic and cultural crisis. The same is true of the many new boots on Russia. I must pen complete issues on these and other discursive topics of this general nature. I crave, therefore, the indulgence of the reader and the understanding patience of the publishers.

IN MY first column I limited myself to books which from one point of view or another dealt with our confused modern culture and its perplexing problems and conflicts, and how historically they came to be what they are today. I was at any rate historically minded in that article. And if James Harvey Robinson is to be relied on that is the prime condition of civilized maturity. My intention was to recommend a restricted number of volumes on a related subject but with different points of view. Each author approached his subject in his own way and emphasized aspects and factors which he considered significant. But even with such a principle of choice guiding me I was unable to include equally desirable books embodying yet more divergent points of view and canons of thought. Supplementary to those on my first list I am happy to add the following:

1. Expression In America: Ludwig Lewisohn. Harper and Bros.

2. American Literature: R. Blankenship. Henry Holt.

3. The Soul of America: A. H. Quinn. University of Pennsylvania Press.

These books also concern themselves with the expression of the American mind in and through literature and criticism. The best of the three is Lewisohn's. It is a capital book in many ways. Blankenship's "American Literature" manifests the same cycle of ideas and critical judgments as we found in Parrington. But it lacks the vigorous thought of Parrington's study, although it has the merit of being compressed into one volume. Only one-half of Quinn's "TheSoul of America" is worth recommending. That may be termed his better half. The male half is inferior. If this critical stinginess of mine goes much further I shall be recommending just one or two chapters in certain books, and maybe not even that in some cases. Ultimately, I may be driven to write on what cannot be recommended. And why?

Lewisohn's interpretation of American expression has the rare qualities of freshness and individuality besides an enviably lucid and critical acumen. In fact it possesses so many engaging features that it should be read along with those recommended previously. However, it invites criticism for its occasional hypersensitiveness if not squeamishness. This is revealed principally in its strictui-es on the puritanic pattern in American life and thought. Lewisohn tends to read too much into puritanism and then use that in such a way as to over-simplify his task as a critic. Interpreters of American culture should scrutinize acutely their understanding of historical puritanism together with their own working set of anti-puritanic assumptions. The author is likewise vulnerable for applying Freudian principles of relative validity a little too facilely in some of his interpretations. Both of these tendencies point to regrettable lapses of sound critical judgment. They make criticism too superficial, if not irrelevant and sterile. With these reservations I can praise "Expression in America" very heartily. Lewisohn has a number of other works to his credit, including his revealing "Up-stream." I shall discuss some of these in a later issue in connection with another topic.

I regret that considerations of space do not allow me to expand the criticisms I may make of the books I mention. The ideas and interpretative principles in Lippmann and Briffault and Calverton are open to considerable criticism. I am of the opinion also that the confusion of descriptive and interpretative uses made of the frontier and its influence by certain writers should be submitted to rigorous criticism. This has not been done to the extent demanded by its vogue in contemporary historical writing. Three or more conflicting meanings seem to be attributed to the frontier. Some ascribe an exaggerated causal efficacy to it as a factor shaping American history. Others view it as synonymous with a new geographical area, or the simple pioneering type of culture introduced into that geographical area, while still others think of it as the resultant effect of the mutual inter-actions of these two things. Some use it descriptively, others interpretatively; some regard it as a determinative influence, and others as only one among many other conditioning factors. More exasperating yet is the habit of some writers when in difficulties to forget the meaning already attached by them to the frontier and seek an easy refuge by an uncritical recourse to race or blood as an explanatory principle. The distinguished author of "The Epic ofAmerica" is not free from this illogical procedure. I feel about the same with respect to the uses made of the frontier as 1 do about puritanism. It is tempting to use both uncritically. And to do that is at best confusing and at worst, impotent. There is room for a severely analytical article or even book on this tendency. I suggest that as a theme for a magazine article by perhaps one of our own unemployed alumni.

SINCE THE last issue publishers have sent me a number of books as candidates for inclusion in this column. Some of them do not come up to the standards, and for that reason I cannot recommend them. They have no excellence either of form or of substance. I do not see why publishers take a chance with so many distinctionless books. They must be a drain on their resources, and I can testify from my own disenchanting experiences that they are a torturing burden on the spirit of the guileless reader. I would classify a lot of these books under Stuart Chase's "illth."

Among two of the better kind sent me are two on American history and two biographies. The histories are better than the biographies. One is "The Rise of theUnion," the first volume of a contemplated two-volume study on "The March ofDemocracy" by James Truslow Adams. It is published by Charles Scribner's Sonsprice $3.50. This vivid and well-illustrated history is likely to become popular. It is more descriptive and factual than the "Epic." He generalizes and interprets less in this work, but it has the same vigorous narrative style and the same trenchant expression. On the whole it stresses the political and social factors in American history, without by any means underemphasizing the economic and the cultural. However, candor impels me to say that it shows signs of hasty writing here and there. A scholar like Adams should be more careful in his references to Indians and the Indian race, as if that race and culture were more homogeneous than American anthropologists have found them to be. Neither is it consonant with anthropological practice to refer to them so many times as savages. There are other minor inaccuracies in the book which Mr. Adams should have avoided—especially in view of his intention to make of this study a factual history of America.

The second history is E. C. Kirkland's "History of American Economic Life" published by F. S. Crofts and Co., New York (price $5.00). This is a creditable piece of writing, and will fill a real need. A well-known European economist defined economic history as "the least history for the most money." That somewhat sharp definition fits some economic histories rather well. But it would not cover the book under review, for it contains a great deal of solid substance and I am confident that its perusal will lead to a better understanding of the historical development of American economic institutions as well as American agriculture and commerce. I am constrained to state, however, that what the editor of the series to which it belongs conceives to be one of its strongest points I consider one of its weaknesses. This is its treatment of the popular economic philosophies of the conflicting economic groups which have accompanied the growth of American economic life. Less than justice is done to the real but subtle manner in which diversive ways of living affected the modes of thinking of interested classes. Nevertheless the book is as satisfying as anything we have on the same subject and in one volume.

The two biographies which Macmillan and Co. forwarded me are of more doubtful quality. Yet both are better than other biographies portraying the same significant personalities. The biography of Roger Williams by James Ernst (price $4.00) contains some interesting new material, and we are indebted to the author for that reason. The old uncertainty about the early life of Roger is removed effectively. As a matter of fact the book all the way through is first-rate on the factual side. It is almost a definitive biography in that respect. It is nearly as satisfactory in its analysis of the political contributions of Roger Williams. With Mr. Ernst's earlier work on "The Political Ideas of Roger Williams" there is not much of value that can be added on that question. But I cannot say as much on the religious and theological side. The author is not at home in that field. He does not know it well enough. Neither does he give us anything like an adequate portrayal of Roger's personality as a whole. The style is turgid in parts, and occasionally repetitious and pointless. The book is equally deficient in documentation, at least, the documentation is done in an unhelpful manner. Page references are omitted in many cases. These are defects in what is otherwise the most complete biography we have on the life and work of one of the greatest figures in the America of the seventeenth century.

The volume on "The Penns of Pennsylvania" by Arthur Pound (Macmillan Co. —price 53.75) is another biography with dubious virtues. It aims to be a family biography, and in that sense it is interesting. But there are many pitfalls in the way of the writer of a family biography. A certain amount of questionable genetics is bound to creep into one's work. It is difficult also to sustain the interest of the reader as the story progresses from one member to another. Particularly is this true of a family like that of the Penns. I can see that a family like the Huxley clan would lend itself to a magnificent story in the passage from greatness to greatness. It is unfortunate that neither Peterson nor Ayres attempted this in their recent biographies of Thomas H. Huxley. However, Grattan has done an interesting job on his biography of the James family. The trouble with the Penn family was that it lacked the requisite variety of challenging personalities. I was interested in the testy old Admiral of the British Navy —the father of William Penn, the Quaker. And my interest was enhanced throughout the sections on William Penn himself. But after he had gone the way of all the earth I found it hard to keep my interest on the smaller Penns that followed in his wake. Pennsylvania seemed to take my mind away from the story of the lesser known Penns. I was glad that they died out on the male side at least, for I do not know what would have become of the biography or of me if that merciful event had not happened. I have not read the other recent biography of William Penn so I am not in a position to judge which is the better of the two.

SOMEWHERE Goethe advances the thought that "an educated man cannot be dependent for his culture to a narrow circle. The world and his native culture must act on him." Taking a clue from this thought of the versatile German cosmopolitan citizen I shall pass now to his larger world, and refer to some worth while books on some of the countries which have been very much in our newspapers in the last few months. My allusion is to Canada and the Ottawa Imperial Conference; the republic of Spain and its birth-pangs; China and what appears to be her deepening chaos; Manchukuo and the Lytton Report, and Japan and her disquieting policies.

To begin with our neighbor to the north. An excellent book on Canada was published by Scribner's last summer. It is Alexander Brady's Canada. This is one of the volumes in the Modern World series, which aims to interpret the trends and forces shaping the life and thought of contemporary states. The general editor of the series is H. H. L. Fisher. So far seventeen volumes have been issued. The best of them in my opinion are Gooch's Germany (a little out of date now—but still good): Dean Inge's England-, Villari's Italy, Madariaga's Spain-, Hancock's Australia-, Young's Egypt-, and not the least valuable —Brady's Canada. Brady writes with vigor and critical discrimination. There is a larger measure of balanced objectivity in his interpretation than is apt to be the case with books of this nature. Only here and there does he fail in this respect. He does not do justice to the uglier aspects of Canadian industrialism. He is pungent and penetrating in his discussion of the polit- ical, economic, and cultural life of Canada, but not so good on the religious and in- dustrial and French Canadian phases of Canadian culture. I wish someone would write a book on French Canadian culture something similar to Gruening's sterling study of Mexico and Her Heritage.

H. L. Keenlevside's Canada and the United States is also worth reading.

Crossing to the Old World I want to suggest three books on Spain. One is by Havelock Ellis entitled The Soul of Spain, published many years ago but recently reissued. I am fond of most of the books which have come from the prolific brain of Ellis. He is one of the few really all round liberal thinkers we have in the modern world. That is what I like about him. Another small volume on Spain is Karel Capek's Letters From Spain. Capek has a rare capacity for appreciating differences. His Letters From England showed this very well. And now his letters from Spain reveal the same gracious sensitivity, and the same generous appreciation of what is unique in an alien people. The next book relating to one aspect of Spanish life is Ernest Hemingway's Death In theAfternoon, published by Scribner's (price $3.50).

This latest creation of Hemingway cannot be of general interest. His Farewell ToArms was in the main a splendid book. It is one of our best and most honest war books. Some of his short stories I rate highly also. But I did not care for The SunAlso Rises. It petered out ingloriously in a bull-fight. Evidently he is a close student of that ancient institution of Spain, for Death In the Afternoon is a serious book on bulls and bull-fights and bull-fighters and a number of things besides. Lovers of Hemingway will read this volume with pleasure. But those who do not care for his other works will not care for this one. I am not markedly interested in the science and art of bull-fighting. I am not an aficionado. Nevertheless I read this study with more than a modicum of interest. I read even the long glossary at the end. Now and then I was exasperated by some of his indecorous digressions. To use the language of the book there is probably a deal of psychological method in his picador digressive thrusts. I enjoyed some of his sly digs. His comments on art and life and passion and death were illuminating. Yet Hemingway is not so convincing in his philosophizing as in athletic dialogue and vivid conversation. His spare and supple style is better suited to action and movement. In reading Death In the Afternoon I sensed anew some of his limitations. Using his own words in describing good and bad bulls I conclude that he does not charge straight. And critical matadors like myself like literary bulls that charge straight. This he does not do. Enough said.

I come now to the disturbed areas in the Orient. On China an excellent volume is Peffer's The Collapse of a Civilization. Sherwood Eddy's The Challenge of Asia will appeal to those who like Eddy's crusading type of idealism. Sokolsky's TheTinder Box of Asia is journalistic, but very helpful. It is much more than an interpretation of the crisis in Manchuria. Japan, Russia, and China are brought into the illuminating picture. But among a host of other serviceable books on China I think that perhaps the best interms of a vivid and convincingly human interpretation of Chinese life are the four novels of Pearl S. Buck. Three of them are published by John Day. The Young Revolutionist (not so good as the others) is issued by The Friendship Press. The finest of the four is that best seller— The Good Earth. The sequel to that movingly human story is Sons. It, too, is very appealing. These novels of Pearl Buck are of authentic value to the person desirous of understanding modern China.

Turning to Japan, there is a new study by I. Nitobe. It belongs to the ModernWorld series which I have recommended already. It is not as satisfactory as Brady's Canuda. It has some omissions and limitations. And it is not objective enough. It is surprising how difficult it is for native writers in a country which is oppressed or is in any way on the defensive to write objectively and critically about their own culture. Over and over again one is impressed by this interpretative limitation of patriotic writers. And what a number of flabby and relatively useless books of this nature we have witnessed in the last twenty years. I suppose it all points to the defensive, compulsive, and rationalizing character of a great deal of what passes for human thought. How difficult it is to transcend these discouraging deficiencies of our thinking. And yet it can be done. All great and noble books demonstrate that it can be done. But not easily. Two other volumes on Japan are worth knowing. One is The Changing Fabric of Japan by M. D. Kennedy, and the other is W. R. Crocker's, The Japanese Population Problem. I personally find Lafcadio Hearn's sensitively poetic volumes on his spiritual home very revealing. Two rather good books on Manchuria are Manchuria by Owen Eattimore, and an English volume entitled Manchuria: The Cockpit of Asia, by Colonel P. T. Etherton and H. H. Tiltman.

IHAVE received a few letters from some of the alumni about books. Two of them allow of an answer through this column. In response to the letter asking my opinion about what recent novels I have found worth reading I am glad to list the following:

1. Midsummer Night Madness: Sean O'Faolain. This is a collection of tales of the so-called Irish rebellion. It is a first work by an unknown (to me) young Irish writer. It has a delicate and rare distinction in its beautiful style and effective portrayal of character. Read it —particularly the story which gives the book its title. Here is a promising Celt.

2. Brave New World: Aldous Huxley. One of Huxley's best. He is pitiless and cerebrally aggravating. I shall have to discuss Huxley in a later issue.

3. The Fountain: Charles Morgan. This has become a best seller. It has some excellent qualities and not a little graceful writing. It has a distinctive flavor in style and thought. But it falls short of greatness. Its characterization is good but somewhat attenuated. And its suffusive and seductive mystical philosophy is too thin and formless, although I suspect that this is what many of its readers like mainly in the novel. The author is sensitive to the subtler nuances of human emotions.

4. The Hatter's Castle: A. J. Cronin. A first novel with some uncommon features. Not really first-rate. Yet worth reading. Read The House with the Green Shutters along with it.

5. Beyond Desire: Sherwood Anderson. This has some interest to me. But it is not too satisfying. It is concerned with the coming of industrialism into a Southern community. Like most of Anderson's books the early promise is never carried out. He has a rare understanding of innerly tortured men and women, and is acutely aware of the agonizing sturt and strife of modern life. But his ideas and creative faculties do not seem to be equal to the task he sets for himself.

6. Two books of genuine interest to me were: Men and Memories, by Sir William Rothenstein. Rothenstein was a real artist and possessed a fine and sensitive mind. Enjoyable reading if the period from 1872 to 1920 in English art and letters and politics appeals to you.

7. Return To Yesterday: Ford Madox Ford. Three-quarters of this book are splendid. But like most of his books it peters out in a tantalizing manner—a very disagreeable characteristic of Ford. There is also an egoistic element in Ford which jars me now and then. Answering very briefly the inquiry of J. F. about books on recent philosophy, I suggest the following:

1. The Strife Against Duality: A. O. Lovejoy. A critical treatment of the development and difficulties of dualistic systems of thought. Difficult reading but worth it.

2. Realism: Hasan. First-rate in exposition of the ideas and systems of modern realists. Not too satisfactory in critical evaluation. Good on Moore, Russell, Cook, Wilson, Holt.

3. Introduction to Philosophical Analysis: Burnham and Wheelwright. Covers a wide field in a relatively simple manner.

4. The Philosophical Implications of Modern Science: Joad. Not very satisfactory and not as good as one or two of his other books.

5. Reason and Nature: Morris Cohen: Expressive of a robust faith in reason. Good on the philosophy of nature, but not so good on society and the social sciences.

I must postpone other books on philosophy to a later and separate issue, as I have said more than enough for this month.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE PERSONALITY OF WEBSTER

November 1932 By Claude M. Fuess -

Sports

SportsTHIS GAME OF FOOTBALL

November 1932 By Edwin B. Dooley -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment on the Opening Address

November 1932 -

Article

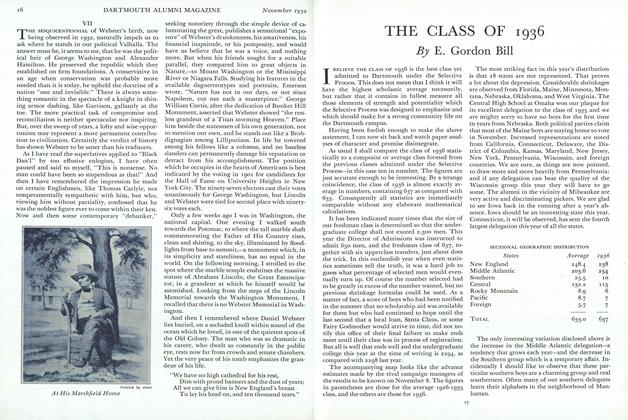

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1936

November 1932 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1932 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

November 1932 By C. E. Leech

Rees Higgs Bowen

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

January 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen