President Hopkins, requested by Senator Bingham to state his position with regard to the Eighteenth Amendment, wrote a letter to the Senator under date of April 8 reiterating his previously expressed opposition to the Amendment and his belief that it should be repealed. The letter was given to the press by Senator Bingham April 15, when it was read into the Congressional Record. It was carried by the press associations April 15 and 16, and because it was frequently abridged to the detriment of its full meaning we are printing it in full, as follows:

Dear Mr. Senator: In answer to your inquiry whether I should be willing to write you my views concerning the Eighteenth Amendment, I am perfectly willing to state my position.

I am opposed to the Amendment and I believe that it should be repealed. Until two years ago I withheld from public statement of my conviction that the principle of the law was wrong because I assumed that the practice might show possibilities of public advantage sufficient to outweigh what seemed to me the fallacies of its theory. I have come to the point now, however, where I not only believe that the repeal of this Amendment is important but, moreover, I believe it is fundamentally vital to the welfare of the country at large.

There are few major problems, social, economic, or political, before the country which are not being complicated and made more difficult of solution by the existence of this Amendment. In the impossibility of its enforcement it works disastrously to respect for law and creates demoralizing disdain of government. It is corroding the standards of public morality and it is insidiously debasing the code definitive of what constitutes desirable personal conduct. Socially its effect has been to provide a subsidy for the underworld by which criminals are being given unprecedented power and by which viciousness is being increasingly protected. Vast moneyed resources have been made available for the corruption of the public service by virtual assignment to anti-social groups of the large sums which formerly, in the excise, went to relieve the financial burdens of government.

The saloon in its old-time form has gone, and is good riddance. However, it is not entirely clear to me that this gain is as complete as proponents of the Amendment claim it to be, when I consider the apparent effect on the body politic of the furtive dives and the gilded speakeasies which steadily increase in number in country and town.

All in all I am rapidly coming to the conviction that the most vital political issue before the country is the extent to which pride of opinion as to what prohibition ought to do is blinding us to what it actually is doing. I am not so much concerned about what happens to my own generation. It has made its bed and might well be left to lie upon it, if that were all there were to it. My concern and my deep solicitude are for the welfare of the oncoming generations. For them the ideal of temperance has been tarnished, and to their imaginations is being given an illusory impression of romantic adventure in condoning weakness and vice and crime.

It is said that Sir Edward Troup, for many years the able Permanent Secretary of the Home Office in England, judged all proposals for the introduction of legislation to govern social evils on the basis of three fundamental principles.

The first was: Not to make crimes, unless forced to do so, out of things which were not crimes already. The second was: Not to introduce prohibitibr

prohibitive legislation beyond the standard of conduct which will be accepted by the sentiment of the country.

And the third was: Not to throw on the guardians of law and order burdens greater than they could bear.

These seem to me principles desirable for consideration, anywhere, at any time, within a democracy. I am

Very respectfully yours, ERNEST M. HOPKINS

The Honorable Hiram Bingham, United States Senate, Washington, D. C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

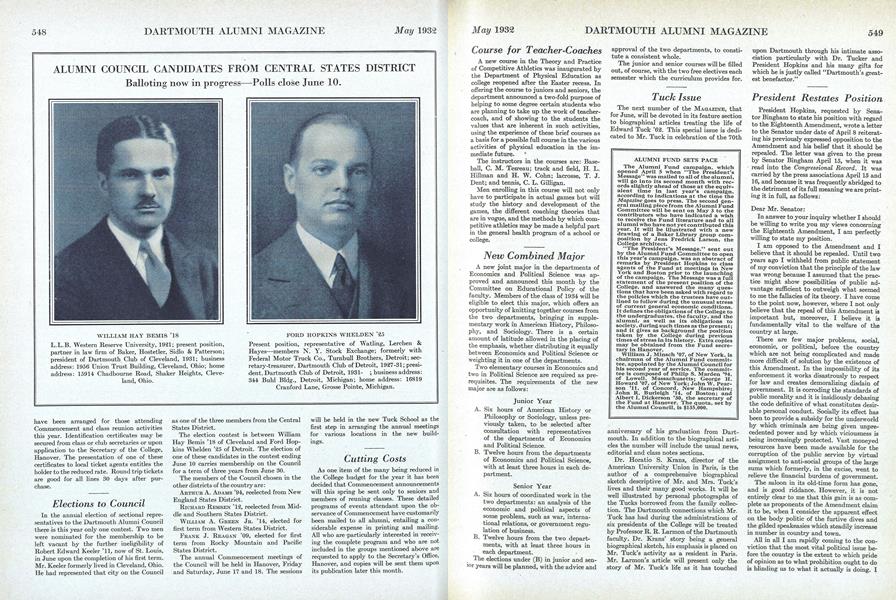

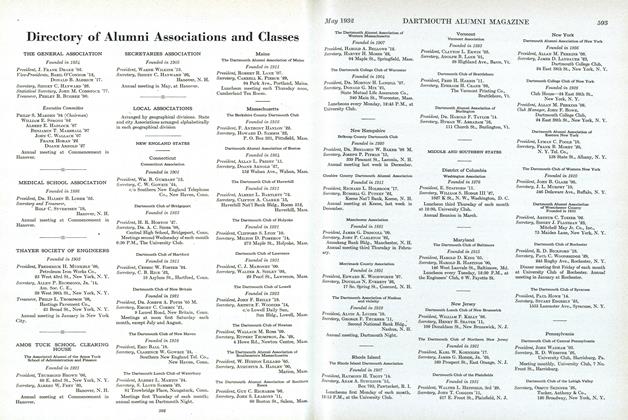

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

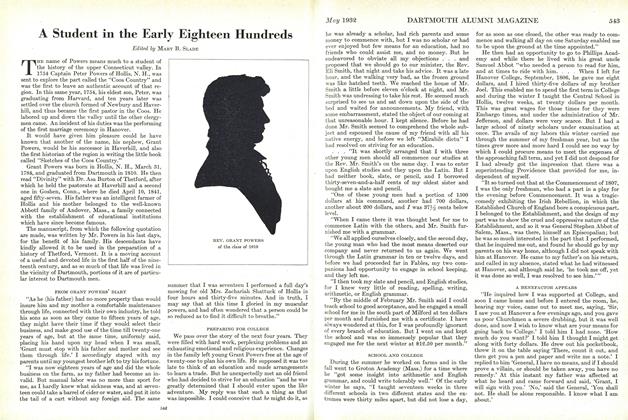

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D.

Article

-

Article

ArticleFreshman Baseball

June, 1911 -

Article

ArticleGRADUATES OF ASSOCIATED SCHOOLS RECEIVE POSITIONS

June, 1912 -

Article

ArticleINFORMATION DESIRED CONCERNING HOWARD W. LINCOLN '15

February, 1923 -

Article

ArticleVice Lord

JANUARY 1969 -

Article

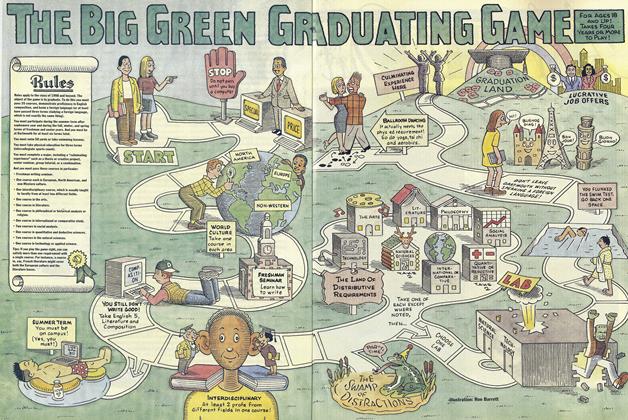

ArticleThe Big Green Graduating Game

December 1994 -

Article

ArticleNo Halt in the Alumni Fund

OCTOBER 1967 By RALPH LAZARUS '35