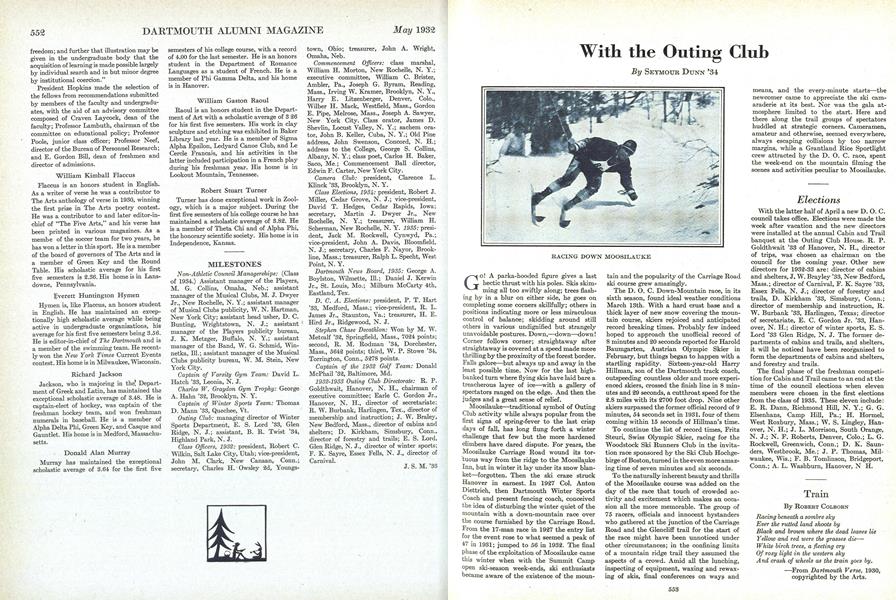

Go! A parka-hooded figure gives a last hectic thrust with his poles. Skis skimming all too swiftly along; trees flashing by in a blur on either side, he goes on completing some corners skillfully; others in positions indicating more or less miraculous control of balance; skidding around still others in various undignified but strangely unavoidable postures. Down,—down—down! Corner follows corner; straightaway after straightaway is covered at a speed made more thrilling by the proximity of the forest border. Falls galore—but always up and away in the least possible time. Now for the last highbanked turn where flying skis have laid bare a treacherous layer of ice—with a gallery of spectators ranged on the edge. And then the judges and a great sense of relief.

Moosilauke—traditional symbol of Outing Club activity while always popular from the first signs of spring-fever to the last crisp days of fall, has long flung forth a winter challenge that few but the more hardened climbers have dared dispute. For years, the Moosilauke Carriage Road wound its tortuous way from the ridge to the Moosilauke Inn, but in winter it lay under its snow blanket—forgotten. Then the ski craze struck Hanover in earnest. In 1927 Col. Anton Diettrich, then Dartmouth Winter Sports Coach and present fencing coach, conceived the idea of disturbing the winter quiet of the mountain with a down-mountain race over the course furnished by the Carriage Road. From the 17-man race in 1927 the entry list for the event rose to what seemed a peak of 47 in 1931; jumped to 56 in 1932. The final phase of the exploitation of Moosilauke came this winter when with the Summit Camp open ski-season week-ends, ski enthusiasts became aware of the existence of the mounlain and the popularity of the Carriage Road ski course grew amazingly.

The D. 0. C. Down-Mountain race, in its sixth season, found ideal weather conditions March 13th. With a hard crust base and a thick layer of new snow covering the mountain course, skiers rejoiced and anticipated record breaking times. Probably few indeed hoped to approach the unofficial record of 8 minutes and 20 seconds reported for Harold Baumgarten, Austrian Olympic Skier in February, but things began to happen with a startling rapidity. Sixteen-year-old Harry Hillman, son of the Dartmouth track coach, outspeeding countless older and more experienced skiers, crossed the finish line in 8 minutes and 29 seconds, a cutthroat speed for the 2.8 miles with its 2700 foot drop. Nine other skiers surpassed the former official record of 9 minutes, 54 seconds set in 1931, four of them coming within 15 seconds of Hillman's time.

To continue the list of record times, Fritz Steuri, Swiss Olympic Skier, racing for the Woodstock Ski Runners Club in the invitation race sponsored by the Ski Club Hochgebirge of Boston, turned in the even more amazing time of seven minutes and six seconds.

To the naturally inherent beauty and thrills of the Moosilauke course was added on the day of the race that touch of crowded activity and excitement which makes an occasion all the more memorable. The group of 75 racers, officials and innocent bystanders who gathered at the junction of the Carriage Road and the Glencliff trail for the start of the race might have been unnoticed under other circumstances; in the confining limits of a mountain ridge trail they assumed the aspects of a crowd. Amid all the lunching, inspecting of equipment, waxing and rewaxing of skis, final conferences on ways and means, and the every-minute starts—the newcomer came to appreciate the ski camaraderie at its best. Nor was the gala atmosphere limited to the start. Here and there along the trail groups of spectators huddled at strategic corners. Cameramen, amateur and otherwise, seemed everywhere, always escaping collisions by too narrow margins, while a Grantland Rice Sportlight crew attracted by the D. O. C. race, spent the week-end on the mountain filming the scenes and activities peculiar to Moosilauke.

RACING DOWN MOOSILAUKE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1929

May 1932 By Frederick William andres -

Article

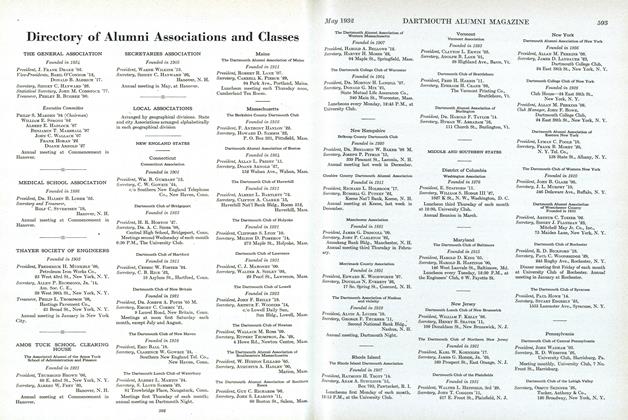

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

May 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPublic or Private Schools: A Letter to the Editor

May 1932 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

ArticleA Student in the Early Eighteen Hundreds

May 1932 By Mary B. Slade -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

May 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleLetch worth Village—A Home for Mental Defectives

May 1932 By Charles S. Little, M.D.