By Ramon Guthrie, Assistant Professor of French.

The Arts Press, in devoting the third of its Chapbooks to Professor Ramon Guthrie's "Scherzo from a poem to be entitled THE PROUD CITY," offers us an example of the allusive, sudden, and complexly shuttling poetry which, under the influence of such poets as Laforgue and Pound, has become increasingly characteristic of the twentieth century.

The "Scherzo" represents, as Professor Guthrie puts it, "one-quarter of a poem concerned with Elmer Griswold in quest of the Proud City, a symbol too precise in itself to permit of explanation. Elmer Griswold is a New Englander of old stock, brought up in the smug, inanimate slums of a Connecticut manufacturing community." Elmer's quest is represented only partly, however, through realistic snatches of modern life—tea in an esoterically overcultured. salon in Paris, a clattering machine-shop, a New England uncle stalking God with a shot-gun out behind the barn. In part, Elmer's quest is presented through imagery drawn from Biblical story and Gnostic teaching. For instance, Elmer's mother by her "gentle nagging" of his father is always

"Reminding him that he had killed Abel, Reminding him of Lilith. . . ." The poem, therefore, although fantastic and rapid in movement, as its title indicates, is essentially contrapuntal or fugal in structure. The past is suddenly and intermfttently super-imposed upon the present, so that the present is invested with over-tones of philosophic significance and emotional enlargement. The themes or moods, as well as the images, alternate fugally; wild energy knowing neither good nor evil, utter analytical cynicism and disillusionment, the search for freshness of life, the search for a faith to tranquillize and establish life, are played off one against another. It is not clear to me exactly which of the last two items I have just mentioned defines most nearly Elmer's quest. Very likely Elmer does not know, and is not intended to know; very likely the answer is neither and both. The question could only be settled by reference to the whole poem.

In my opinion, the poem is more remarkable for its general scheme, and the effectiveness with which the component strands are interwoven, then for felicities of particular image or phrase. There is not much of the compact and perhaps bewildering originality of metaphor to be found in such poets as Hart Crane. On the other hand, the rhythms of "Scherzo" seem to me ably contrived and honest; the juxtaposition of today with the Books of Genesis and Revelations in general escapes the charge of emotional facileness—the special danger of the allusive method in incompetent hands; and the reader, after finishing Chapbook No. 3, is left genuinely anxious for further light on Elmer's quest, and genuinely interested to discover by what themes this quest is to be defined and enriched in the remaining three-quarters of the poem. In the selection and ordering of its items, Professor Guthrie's poem justifies its claim to our interest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

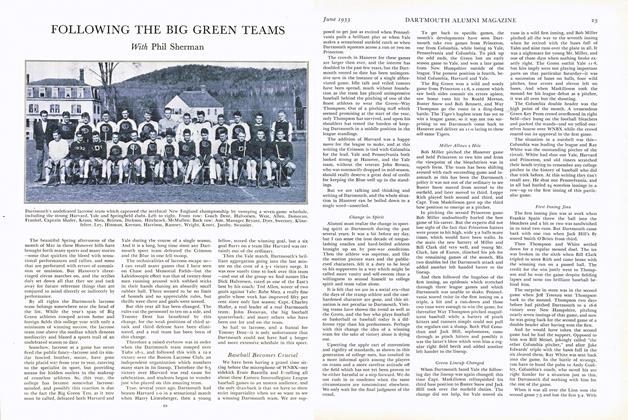

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

June 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

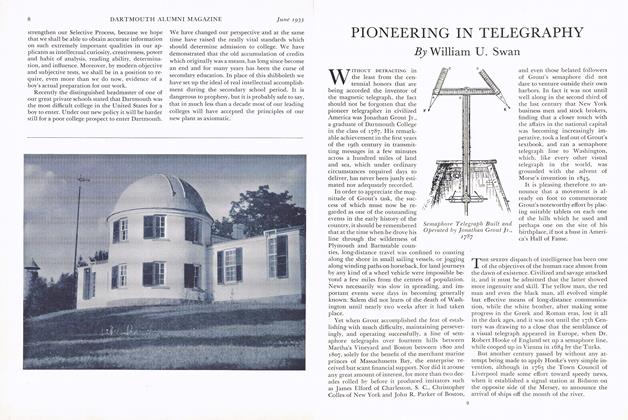

ArticlePIONEERING IN TELEGRAPHY

June 1933 By William U. Swan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of IQ9 1

June 1933 By Jack R. Warwick -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Convene

June 1933

Books

-

Books

BooksShelf Life

Sep - Oct -

Books

BooksROBERT SALMON: PAINTER OF SHIP & SHORE.

DECEMBER 1971 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksMEASUREMENTS OF BIRDS

JUNE 1932 By Everett C. Myers -

Books

BooksHOGARTH ON HIGH LIFE. THE MARRIAGE A LA MODE SERIES FROM GEORG CHRISTOPH LICHTENBERG'S COMMENTARIES.

DECEMBER 1970 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksA GUIDE TO BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS AND THERAPY.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksMethods and Standards for Local School Surveys

March 1919 By WALTER M. MAY