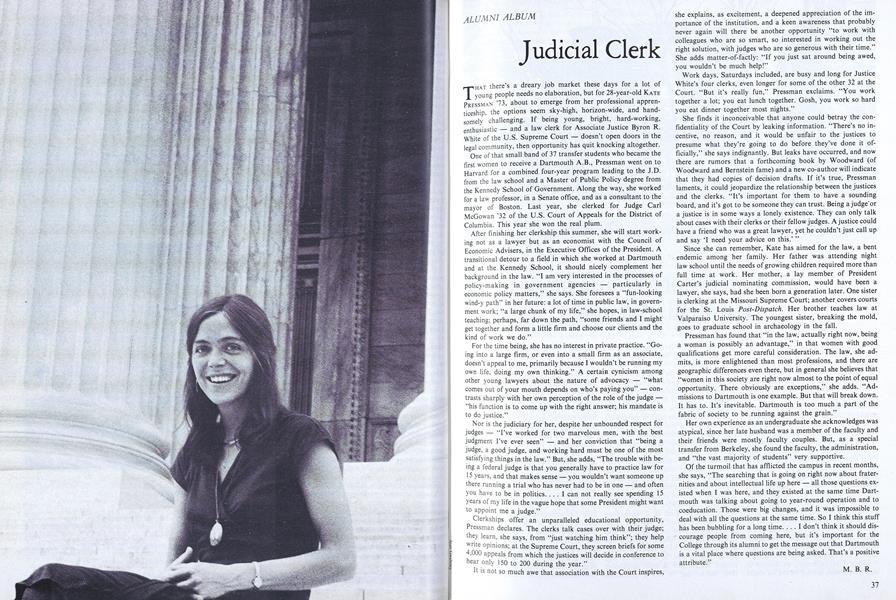

THAT there's a dreary job market these days for a lot of young people needs no elaboration, but for 28-year-old KATE PRESSMAN '73, about to emerge from her professional apprenticeship, the options seem sky-high, horizon-wide, and handsomely challenging. If being young, bright, hard-working, enthusiastic - and a law clerk for Associate Justice Byron R. White of the U.S. Supreme Court - doesn't open doors in the legal community, then opportunity has quit knocking altogether.

One of that small band of 37 transfer students who became the first women to receive a Dartmouth A.B., Pressman went on to Harvard for a combined four-year program leading to the J.D. from the law school and a Master of Public Policy degree from the Kennedy School of Government. Along the way, she worked for a law professor, in a Senate office, and as a consultant to the mayor of Boston. Last year, she clerked for Judge Carl McGowan '32 of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. This year she won the real plum.

After finishing her clerkship this summer, she will start working not as a lawyer but as an economist with the Council of Economic Advisers, in the Executive Offices of the President. A transitional detour to a field in which she worked at Dartmouth and at the. Kennedy School, it should nicely complement her background in the law. "I am very interested in the processes of policy-making in government agencies - particularly in economic policy matters," she says. She foresees a "fun-looking wind-y path" in her future: a lot of time in public law, in government work; "a large chunk of my life," she hopes, in law-school teaching; perhaps, far down the path, "some friends and I might get together and form a little firm and choose our clients and the kind of work we do."

For the time being, she has no interest in private practice. "Going into a large firm, or even into a small firm as an associate, doesn't appeal to me, primarily because I wouldn't be running my own life, doing my own thinking." A certain cynicism among other young lawyers about the nature of advocacy - "what comes out of your mouth depends on who's paying you" - contrasts sharply with her own perception of the role of the judge - "his function is to come up with the right answer; his mandate is to do justice."

Nor is the judiciary for her, despite her unbounded respect for judges - "I've worked for two marvelous men, with the best judgment I've ever seen" - and her conviction that "being a judge, a good judge, and working hard must be one of the most satisfying things in the law." But, she adds, "The trouble with being a federal judge is that you generally have to practice law for 15 years, and that makes sense - you wouldn't want someone up there running a trial who has never had to be in one - and often you have to be in politics. ... I can not really see spending 15 years of my life in the vague hope that some President might want to appoint me a judge."

Clerkships offer an unparalleled educational opportunity, Pressman declares. The clerks talk cases over with their judge; they learn, she says, from "just watching him think"; they help write opinions; at the Supreme Court, they screen briefs for some 4,000 appeals from which the justices will decide in conference to hear only 150 to 200 during the year."

It is not so much awe that association with the Court inspires, she explains, as excitement, a deepened appreciation of the importance of the institution, and a keen awareness that probably never again will there be another opportunity "to work with colleagues who are so smart, so interested in working out the right solution, with judges who are so generous with their time." She adds matter-of-factly: "If you just sat around being awed, you wouldn't be much help!"

Work days, Saturdays included, are busy and long for Justice White's four clerks, even longer for some of the other 32 at the Court. "But it's really fun," Pressman exclaims. "You work together a lot; you eat lunch together. Gosh, you work so hard you eat dinner together most nights."

She finds it inconceivable that anyone could betray the confidentiality of the Court by leaking information. "There's no incentive, no reason, and it would be unfair to the justices to presume what they're going to do before they've done it officially," she says indignantly. But leaks have occurred, and now there are rumors that a forthcoming book by Woodward (of Woodward and Bernstein fame) and a new co-author will indicate that they had copies of decision drafts. If it's true, Pressman laments, it could jeopardize the relationship between the justices and the clerks. "It's important for them to have a sounding board, and it's got to be someone they can trust. Being a judge or a justice is in some ways a lonely existence. They can only talk about cases with their clerks or their fellow judges. A justice could have a friend who was a great lawyer, yet he couldn't just call up and say 'I need your advice on this.' "

Since she can remember, Kate has aimed for the law, a bent endemic among her family. Her father was attending night law school until the needs of growing children required more than full time at work. Her mother, a lay member of President Carter's judicial nominating commission, would have been a lawyer, she says, had she been born a generation later. One sister is clerking at the Missouri Supreme Court; another covers courts for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Her brother teaches law at Valparaiso University. The youngest sister, breaking the mold, goes to graduate school in archaeology in the fall.

Pressman has found that "in the law, actually right now, being a woman is possibly an advantage," in that women with good qualifications get more careful consideration. The law, she admits, is more enlightened than most professions, and there are geographic differences even there, but in general she believes that "women in this society are right now almost to the point of equal opportunity. There obviously are exceptions," she adds. "Admissions to Dartmouth is one example. But that will break down. It has to. It's inevitable. Dartmouth is too much a part of the fabric of society to be running against the grain."

Her own experience as an undergraduate she acknowledges was atypical, since her late husband was a member of the faculty and their friends were mostly faculty couples. But, as a special transfer from Berkeley, she found the faculty, the administration, and "the vast majority of students" very supportive.

Of the turmoil that has afflicted the campus in recent months, she says, "The searching that is going on right now about fraternities and about intellectual life up here - all those questions existed when I was here, and they existed at the same time Dartmouth was talking about going to year-round operation and to coeducation. Those were big changes, and it was impossible to deal with all the questions at the same time. So I think this stuff has been bubbling for a long time I don't think it should discourage people from coming here, but it's important for the College through its alumni to get the message out that Dartmouth is a vital place where questions are being asked. That's a positive attribute."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer -

Feature

FeatureA Three-story House on Bramhall Avenue

May 1979 By Douglas Andrews -

Article

ArticleHearts and Minds Study

May 1979 By TIM TAYLOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1979 By WILLIAM A. CARTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

May 1979 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeatureGuatemalan Cane Raiser

APRIL 1973 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureRock chronicler

May 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleColonial Chronicler

May 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

MAY 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R.