By popular election and administrative review, committees were set up in dormitories and fraternities to govern student activity and to act as student representatives in cases of discipline. These men agreed to promote gentlemanly conduct through the year and to care for the individual problems of their own group.

This movement was regarded with varied opinions among the students, but all were serious about it and entered willingly into the spirit of the enterprise.

To date, the whole matter of student control is still open to discussion and change. It has not been perfect in its workings, but it has shown that it embodies many sound principles. The idea is still young and the organization is not old enough to withstand severe strains, but for ordinary college life it functions in a manner satisfactory for a new venture.

There are two principal weaknesses in the plan at present. The first and simplest is purely a matter of organization and administration. Time has shown, and will show, places where improvements can be made. Minor acts will be instituted that will increase the strength and appeal of the plan. All that must be promoted through the seasoning influence of time.

The other weakness is in the lack of popular appreciation on the part of many students of certain phases of the plan. Many have not yet realized that the plan is intensely cooperative in nature and that responsibility rests on each individual. There is still a tendency to feel that the committees and chairmen are working against the students, whereas in reality they are protecting the students and giving them intelligent liberties that it would be impossible to give them under administrative police control.

Student control is not an outstanding success at present, but it has shown that it has strength and value. Its future efficacy rests in the ability of the students to realize that only by supporting it with all their individual power can they maintain the enviable position and rights that they now have.

By Wm. W. Fitzhugh Jr. '35 Senior FellowSenior Class Secretary

I LIKE TO HAVE people listen to me. I believe that most people like to have others listen to them. One of my life ambitions is to be able to look back over a long period and find that people have been giving increasing attention to the things I want to say. However, I have by no means reached that point now and there is no justifiable reason for me to discuss the college curriculum at all except that I am an undergraduate in college, have just been through the mill, and conceivably there are those who would like to know my reactions.

In addition to almost complete incompetence because of age and perspective, I have been definitely limited in my experience to a scientific major for the most part, with a few "cultural" courses thrown in because of a system of required educational breadth. So as I stand today, I do not consider myself educated very much. I have been through college, though, and I hope that my vague absorption of a college atmosphere will stand me in good stead.

For the sake of convenience in discussion I have divided the subject personally into two parts: what I like about the curriculum and what I think should be improved. Like most articles, I shall probably talk about the latter phase more than I should.

I liked the idea of a college curriculum from the start. When I first came to college, the vision of two hundred and fifty educated men ready to help me and lead me in whatever field I chose, seemed very intriguing. The subjects they taught were so many foreign countries with their own customs and language. I was a traveler with an American Express check from home, and a benevolent uncle, the administration, tagging along to see that I fell not among thieves.

Perhaps this is very silly; but I felt that way. I was a boy on an adventure. Everything was new, and my confidence was a little shaky. These intricate subjects seemed beyond me. Only the sight of hundreds of others who had somehow or other mastered them cheered me a little. The high estate of a senior who really understood something about all this was quite far away.

Somehow or other I fell into the habit of doing my work day by day, occasionally as a splurge doing it two days in advance. The results were eminently satisfactory: I received good grades. With the time to spare I entered into a number of extracurricular activities.

During this period of about a year and a half, I was very pleased with the curricular college. The courses were for the most part interesting. They were about things which I had known only vaguely and when increased knowledge came, I felt my educational stature growing with that same blush of internal pride which a newly developed muscle occasions. During this period also, however, I seemed to cross that subtle line which divides a rank youth from a somewhat less rank one.

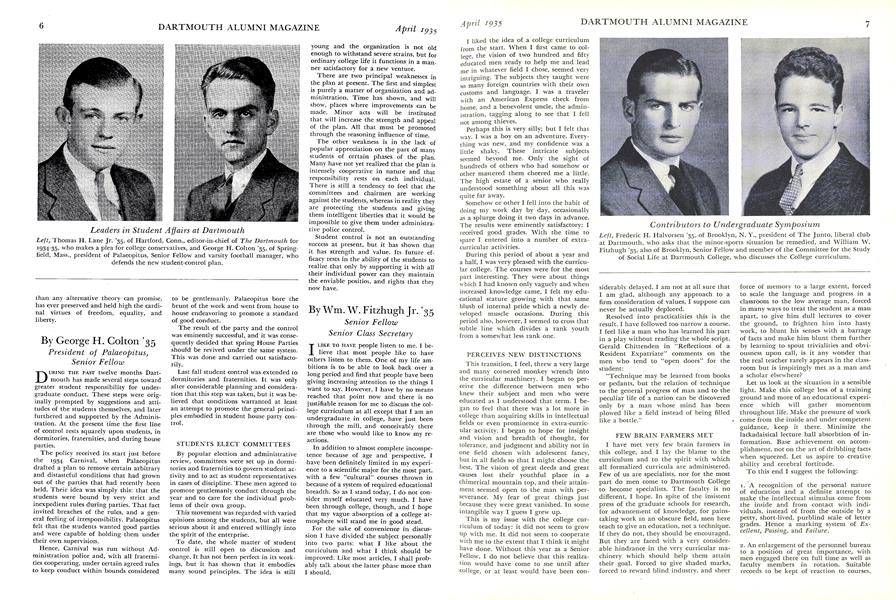

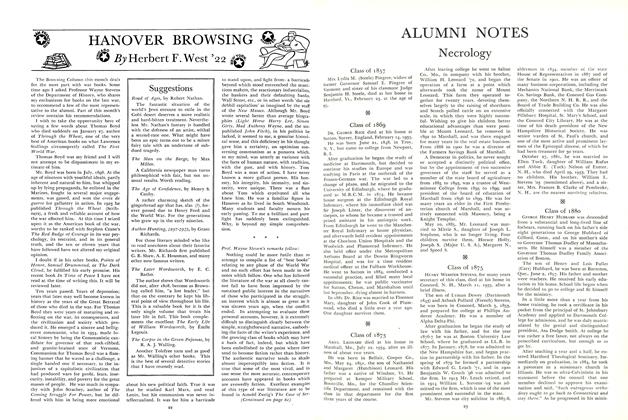

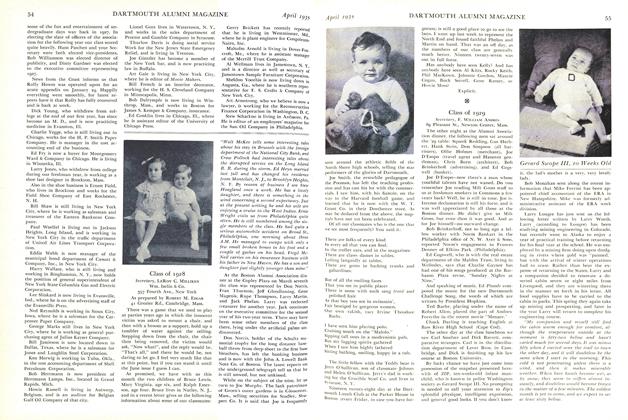

Contributors to Undergraduate SymposiumLeft, Frederic H. Halvorsen '35, of Brooklyn, N. Y„ president o£ The Junto, liberal club at Dartmouth, who asks that the minor-sports situation be remedied, and William W. Fitzhugh '35, also of Brooklyn, Senior Fellow and member of the Committee for the Study of Social Life at Dartmouth College, who discusses the College curriculum.

Contributors to Undergraduate SymposiumLeft, Frederic H. Halvorsen '35, of Brooklyn, N. Y„ president o£ The Junto, liberal club at Dartmouth, who asks that the minor-sports situation be remedied, and William W. Fitzhugh '35, also of Brooklyn, Senior Fellow and member of the Committee for the Study of Social Life at Dartmouth College, who discusses the College curriculum.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleSTABILIZATION BY SPECIE PAYMENTS

April 1935 By Edward Tuck '62 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

April 1935 By L. W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1935 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

April 1935 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

April 1935 By F. William Andres