THE CURRICULUM OF any live institution of learning should not be static. Whether changes should be rare and disturbing as they often have been at Dartmouth when a "new curriculum" burst forth, or frequent and soothing as at present is rather immaterial, although several advantages are obvious in a continuous overhauling of the educational machine. Such a procedure prevents that dangerous self-satisfaction in the assumed perfection of any major effort in curriculum building, it keeps the faculty interested in discovering minor improvements in existing conditions, and it takes cognizance of the trite but important fact that the College is serving a social and physical world which is changing and moving at a speed which would have seemed incredible at the time most of us were in college.

With a realization that the Dartmouth faculty had long since become too large for purposes of useful discussion, the faculty last year voted to arrange itself into three smaller faculties, each with an effective administrative organization: the Division of the Humanities, the Division of the Social Sciences, and the Division of the Sciences.

Recent changes in the curriculum adopted by the faculty, which are the main subject of this paper, emanated from and primarily affect the Division of the Social Sciences, but an attempt will be made to point out how these changes impinge on the other divisions and to indicate ppssible changes in the offerings of these divisions which I personally hope the future may have in store.

PRACTICALLY EVERY educational advance of importance which has been made at Dartmouth during the past two decades, including the introduction of the Selective Process for Admission, which may well be Dartmouth's greatest contribution to educational theory and practice, has been suggested by President Hopkins. He has been the master diagnostician of Dartmouth's educational ills, and the faculty in general has played the role of the cooperative and skillful operating surgeon. During the past two or three years the President, especially in his addresses at the opening of College, has vigorously stressed several points: first, that as a matter of ordinary national protection in these days of violent social change and educational dictatorships and regimentation throughout a large portion of the world, it is essential that an attempt be made to make students "social-minded," and that no student should graduate from Dartmouth College without some training in and appreciation of the causes of these violent and constant social upheavals which are distinctive of this particular period in history. With his usual knack for telling phrases the President said that in this day and generation the social sciences should form the hub of the educational wheel. Second, the President has held that what the world needs is not the viewpoint of narrow specialization in the social sciences but that wisdom which only can come from an open-minded consideration of the economic, historical, political, and sociological implications of any national problem.

The Washington "Brain Trust" is a perfect illustration of an aggravated case of social myopia due to narrow specialization, which, strangely enough, has never infected the Chief Executive. It has probably set back the liberal arts college in the lay mind by at least two decades. This setback possibly is unwarranted and is due to a common loose thinking founded on absurdly inadequate statistics, because I mistrust that a competent statistician could prove that this particularly malignant case of nearsightedness emanated not only from an extraordinarily limited section of the liberal arts mind, but was caused by a viciously narrow specialization.

President Hopkins' broad and clear diagnosis of a disease started the Division of the Social Sciences on a two-year course of intensive intelligent study and hard work by two different and exceptionally able committees. This finally has resulted in recommendations recently adopted by the faculty, which may not be either particularly new or significant in the educational world but certainly represent a step in the right direction. Moreover, they contain one brand new and very promising idea and they are of a nature that should permit and encourage that sort of experimentation that is almost always so much more effective and permanently satisfying than some of these devastating curricular upheavals of which all faculties have been periodically victims. Perhaps it will be of interest to mention that although when any curricular change is contemplated at Dartmouth, a rather thorough study is made of practices at sister institutions; when the child is born it almost always strongly shows its Dartmouth parenthood and its physique is well adapted for life on this particular campus.

THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

THE EXPLICIT CHANGES recently adopted by the faculty include the abolition of the semester courses in Problems of Industrial Society and Evolution; the introduction of two new year-courses, Social Science 1-2 and Social Science 3-4; a change in the so-called social science requirements for the bachelor's degree; the reduction of the present introductory courses Economics 1-2, Political Science i—2, and Sociology 1-2 to one-semester courses; and the replacement of the present joint majors in the social sciences by new "topical majors." At present every candidate for the degree must complete one semester of Problems in Industrial Society and two year-courses to be chosen from two of the six departments of Economics, History, Philosophy, Political Science, Psychology, and Sociology. Under the new requirements all students will be required to carry the new year-course Social Science 1-2 in freshman year—incidentally, they will not be permitted to elect any other courses in the social sciences during freshman year—and to complete in sophomore year either two of the new semestfcr-courses, Economics 1, Political Science 1, and Sociology 1, or the new year-course, Social Science 3-4.

The new course for freshmen, Social Science 1-2, will show the growth of modern institutions covering the period chiefly from the Industrial Revolution to the present time. It will be primarily European in content but relevant American material will be continuously included. It will treat economic, political, and social factors in chronological order, with emphasis on developments since 1870.

The course, Social Science 3-4, which will be offered for the first time in 1937-38, is primarily designed for men who do not expect to major in the social sciences and who do not wish to elect Economics 1, Political Science 1, or Sociology 1. It will be an integrated course in contemporary problems with materials drawn from the fields of Economics, History, Political Science, and Sociology*.

In addition to the present departmental majors in the social sciences there are to be several so-called "topical majors." Such topics as "International Relations," "The Relation of Government to Business," "Social Reconstruction," "Race and Nationality," and others, will furnish the basis of these new majors, which are designed to cut across departments and to give students a chance to integrate materials which they have acquired in individual courses in the various social science departments. These "topical majors" are by all odds the most promising innovation now being introduced. Incidentally, such majors are not only rather new in the educational world, but their inauguration will unquestionably set other divisions to thinking about similar possibilities in their bailiwicks. It may surprise many readers that orientatibn courses are apparently being curtailed at Dartmouth whereas in many parts of the country such things are running wild, some institutions going so far as to make the entire freshman year consist of orientation courses. Apparently the Dartmouth faculty believes that before you can orient students, or build any lasting edifice in the social sciences, it is first necessary to lay a strong foundation such as will be furnished by Social Science 1-2. Furthermore, although throughout the country there is much talk of freshman courses which "integrate" the social sciences, the Dartmouth faculty apparently believes that the student cannot integrate several social sciences until he has got something to integrate; in other words, until he knows at least a little bit about each of these disciplines, can speak their language, and come at least to a hazy realization of their method of attack.

The "topical majors" should furnish a logical, stimulating, and fruitful kind of integration. If a student decides, for example, to major in "International Relations," his program of courses will be selected and he will be guided by a committee representing the four major social sciences so that when he gets toward the end of senior year and has perhaps completed a fairly exhaustive thesis and has prepared for his comprehensive examinations, he should be ready to go forth from this campus with a broad-gauged and intelligent vision of his concern at least with "International Relations."

The reduction to one semester of the elementary year courses Economics 1-2, etc., which so many thousands of alumni studied, will be an advantage. Student interest in advanced courses, which now may have to be slightly modified, will get started early and before it has a chance to be smothered.

EVOLUTION AND INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY

THE DISAPPEARANCE FROM our curriculum of the semester orientation courses in Evolution and Industrial Society, which were introduced here in 1919, needs some comment. Many years' experience with admissions and with freshmen proved conclusively to me that our leading secondary schools always considered Problems in Industrial Society (formerly known as Citizenship) one of the most stimulating courses offered to freshmen in any college. The majority of boys entering Dartmouth after four years of excellent secondary school instruction have found Industrial Society exhilarating. It always has been excellently staffed and whether or not it has been an orientation course in the social sciences, its methods of small-group frank and informal discussion, and its insistence that all sides of any controversial subject be thoroughly canvassed, has, because of its novelty in their experience, greatly excited freshmen about the possibilities of later college courses. Naturally Social Science 1-2 should more than adequately fill the place left by Industrial Society, but the burden of proof will be on its directors, not only in the choice and arrangement of their material but in the type and quality of their instruction.

The history of the course in Evolution furnishes a most interesting experience in educational theory and practice. It was designed originally as an orientation course in the physical and natural sciences, and was introduced over the dead bodies of our science departments, who knew that no such onesemester orientation course in science had ever been or ever could be anything but absurdly superficial. President Hopkins, with his usual inspiration in picking leaders, asked Professor William Patten to head this course. The professor laughed at the idea. He was up to his ears in his own research and for years had had contact with only a few advanced students. He took the job for one year and continued in it with absorbing and increasing interest to the end of his days. Under him the course was anything under heaven except an orientation course in science. It became the vehicle of his own theories of evolution which I presume are far from being generally accepted. He used a book, "The Grand Strategy of Evolution," which he wrote for the course, embodying these theories, and no freshman ever came within a mile of understanding even a small part of it.

Professor Patten was a rather desultory lecturer and he had to lecture, often with slides, right after luncheon and under conditions which would cure the most aggravated case of insomnia. For years I made it a practice to inquire of-freshmen how they were getting on in Evolution. Every single one always said he didn't know what it was all about but that Professor Patten was a grand man. Later, in subsequent college courses and after graduation, this hazily understood course in Evolution became one of the epoch-making experiences in the lives of these young men.

In other words, here was a great personality with a vision, and though the boys could not see it they realized its importance and later were susceptible to little rays of light which illuminated some small fragment of the picture and they became emotionally stirred by a very challenging intellectual conception. After Professor Patten's untimely death, leaving a void in this community that has never been filled, this course in Evolution reverted to its original design—an orientation course in the sciences—and hence was doomed. The material has been excellently arranged and taught with clearness. The boys have understood each part of the course and have passed quizzes to prove it, but those flickering glimpses of a vision which had dominated a great man have been lacking. Evolution as an introductory course in science could never hope to replace Evolution as a course in William Patten.

THE HUMANITIES

ONE BY-PRODUCT OF the changes in the social sciences that, as is so often the case, may be of major value is an almost certain largely increased election by freshmen of courses in The Classical Foundation of Modern Civilization and in Philosophy. Under the present curriculum some four hundred of the freshman free electives are iii Political Science, History, and Economic Geography. In future these courses will be closed to freshmen, whose only free electives, as now contemplated, will be a second foreign language, a second science, The Classical Foundation of Modern Civilization, and one or more courses in Philosophy. The greatly enriched backgrounds furnished by these courses in Classical Civilizations, which are taught at Dartmouth with inspiration, and the discovery of new intellectual horizons under the guidance of the department of Philosophy should furnish a peculiarly satisfactory complement to the social sciences.

Incidentally, there are so many topics involving many of the humanities—literature (native and foreign), art, music, philosophy—the study of which would not only furnish rare intellectual treats but would result in a peculiarly broad and satisfying cultural foundation for future individual development, that I am bold enough to prophesy that the idea of the new topical majors in social science is almost certain to spread to the humanities.

THE SCIENCES

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF Evolution as a required freshman course is the only change in the sciences specifically effected by the new regulations. However, this is an opportunity to express certain personal convictions concerning the place of science in the liberal arts college.

It happens that Dartmouth College, both in staff and equipment, has science departments that are not excelled in any undergraduate institution in the country. At graduate schools and in industrial organizations the records of our graduates who majored in science furnish part of the evidence for this statement. Nothing could be more complete and satisfying than the undergraduate science education we offer to men who hope to earn their livelihood in some domain of science, but the writer believes much more could and should be done for boys who are interested in science just as they may be interested in the theories of Plato, because he believes that science furnishes just as many avenues for cultural development as are furnished by the more traditional disciplines of the classics, philosophy, and literature. It is easy to prove that a very large number of boys at the time they enter college have their major interest in science and yet they take in college only sufficient science to satisfy the requirements for the degree.

Of course a fairly large percentage of these boys had only a sporadic and juvenile interest in science, just as in radio construction, stamp collecting, etc., and at the first impact with the hard work and clear thinking "required in the sciences, their interest evaporated. On the other hand, little attempt has ever been made in liberal arts colleges to sustain a purely cultural interest in the sciences.

I believe that science departments have been derelict in this regard; but a year or two ago Columbia College, which has a degree requirement in science similar to ours, inaugurated a very promising experiment. It is a two-year course in science designed particularly for men who have no expectation of majoring in science or of making their vocations depend especially upon their training in science. Instead of trying, as is usual in such ventures, to cover a multitude of topics in elementary Chemistry, Physics, Biology, and related subjects, this course does a thorough job on those concepts in these sciences which are of fundamental importance, and particularly on those concepts which are the common property of several sciences. Moreover, the mechanics of the course recognize the vitally important fact that some minds and nervous systems are so constituted that the personal performance of experiments needing a certain amount of manual manipulation is very harmful to the student's appreciation of the real significance of these experiments.

The writer has always been able to profit by experiments performed by other people. He has usually understood them and his imagination, unretarded by manual manipulations, has usually been able to realize something of their broader implications. But the very instant the experiment is in his own hands his imagination and mental processes seem to become atrophied. In all probability science departments have not been willing to admit that this is a common type, and yet it is this fact, I believe, which has deterred so many boys interested in science from doing much science work in college. They simply are unwilling to spend a year or more going through the grind of experiments which are so necessary in the training of future scientists.

The Columbia course saves much time and enhances interest by depending largely on experiments performed by the teacher, although opportunity is also given for individual experiments by the students when they happen to have the type of mind that likes and profits by them. The course at Columbia is moulded into a unified whole by emphasis on those great concepts which are common to the sciences, and it is lightly bound up with the thread of Evolution. I would not only like to see a two-year course like this replace and amplify our old one-semester course in Evolution, but would also like to see inaugurated some advanced cultural courses covering modern developments in the sciences. These developments during the last few years in atomic structure, cosmic rays, and neutrons, which are bombarding the boundaries between physics and chemistry, and the advance in our knowledge of genes and chromosomes, which have hastened the creation of new species almost by eons, all of which advances have literally annihilated the theories taught our generation as facts, are, to me of the most engrossing interest. They stir the imagination like few other explorations. Many of our students should have an opportunity to learn of them. Years of laboratory experimentation are not necessary to understand them. Finally, therefore, I would go one step further and state the belief that the introduction of cultural majors in the science departments for students acutely interested in science, but who perhaps are going to be bond salesmen or lawyers or clergymen, would be one of the most interesting experiments a college such as Dartmouth could originate.

NOVELTIES

As THIS is A SORT of compendium of crime designed L for the edification of the alumni, it may be of interest to mention some educational innovations which have recently been introduced on this campus. The order of their mention herein has no connection whatever with their present or perhaps future importance.

President Hopkins, throughout the years, has often mentioned his desire to have on our faculty distinguished teachers who would have sufficiently broad interests, experience, and training so that they could not be bound within the confines of any particular department. This year Professor Rosenstock-Huessy joined the faculty with the title—of course he had to have one—of Professor of Social Philosophy and became, at least in name, associated with the department of Philosophy. Professor Rosenstock-Huessy is a distinguished and profound German scholar who, by academic training and contacts, by experience in practical social problems in Germany, and in the writing of several important books, has a peculiarly broad vision of the philosophy which underlies our whole social order. As the years go on he should become increasingly effective in leading students across the obvious, as well as the hidden, boundaries which constantly threaten to separate the present social sciences.

As the Selective Process has become more and more refined in its operations, attention has been paid increasingly to placing individual students in college at their proper intellectual levels. In many departments at the present time students, at the time of their entrance, are, from the evidence of school records and from the results of tests given after admission, placed on sophomore or even higher levels in individual courses. This is nothing particularly new at Dartmouth, nor are we doing anywhere near as much with it as at some other institutions, notably Princeton,, where in individual cases nearly a whole year of college work may be jumped, but educationally and intellectually it is of obvious importance. Nothing is more enervating to a well-trained and very capable boy than to be forced to proceed for a year at a level deridely below the horizon which his intellect and equipment have given him.

Although many people know what a handicap any student suffers by being able to read only at a very slow rate, few realize what unbelievable improvement can be made in an extraordinarily brief time in such cases by the advice of experts, usually psychologists, who have been trained in this work. For several years we have been helping a few slowreading freshmen who obviously were suffering from this severe handicap, but next year this work is to be greatly enlarged with the hope that all freshmen, and also upperclassmen, who have a serious handicap in their reading speed, may be given attention and relief.

Since these studies will be carried on with the active cooperation of the Department of Research in Physiological Optics they should be of peculiar significance as there will be established a much better balance between the physiological and psychological factors involved than has been possible elsewhere.

This year Dartmouth brought to her staff an expert in speech defects and he is giving his whole time to directing a thoroughly up-to-date clinic, well equipped with recording and other apparatus. All freshmen are being examined for speech defects and many upperclassmen are coming to the clinic, either of their own volition or at the suggestion of some friendly adviser. It probably will be no surprise to alumni to know that as many as seven well recognized and distinct defects of speech have been discovered here in a single individual. The most common defects are functional and organic, including faulty and confused enunciation, difficulties due to the velar sphincture, many phonetic difficulties, nasal obstructions, cluttering, rhythm and melody defects, persistent baby talk, and hypersecretion of saliva. No argument is needed to prove the great benefit the College is giving to these boys if the worst of these defects can be remedied. The Wilson Museum, which few alumni have ever heard of, although it has been here for many, many years, has taken on a new lease of life through the appointment a year or two ago of a male supervisor, a Cambridge University man with a flair for quiet research and that rare and valuable faculty of inspiring boys to a voluntary interest in museum work. Under him the museum has not only made for itself a place of interest and education on this campus, but the supervisor has gathered around him a group of voluntary workers from the undergraduate body, many of whom will go on with museum work as a vocation. Local fauna and flora can no longer bask in the thought that they will not become specimens.

As this article is being written there comes to my desk a very charming letter from a young man in Montana who presents arguments for becoming a member of the Dartmouth faculty in order to give a new and special course which would consist of expert instruction in the following arts: tying flies; making rods, lures, leaders and nets; repairing reels, rods, and splicing lines; the breeding, care, training and diseases of bird dogs; the handling and care of rifles, shotguns, and pistols; casting, hunting, and fishing lore; buying, jobbing, and merchandizing sporting goods.

THE BACHELOR'S DEGREE

IN THESE FINAL paragraphs I would like to range a bit into the hazy and probably distant future.

For many years it has been somewhat aggravating to hear from innumerable executives and administrators the criticism that the A. B. degree was peculiarly promiscuous, that the promise for any sort of future performance by a group of A. B. men from the same or different institutions varied all the way from Aleph to Thav and just about as much as though they didn't have such a degree. Moreover, college officials have always realized that large numbers of the most accomplished members of the alumni body either had mediocre scholastic records in college or left before graduation, unquestionably because of the failure of the college program to excite their real interests and discover their real abilities. Although I am statistically still willing to give very big odds in favor of the boy who has done superior scholastic work in college—in other words, has done one of his first jobs well—there is no answering the criticisms impiied above. Now finally, the damage done in the lay mind to the Bachelor's and other academic degrees by the activities of the Brain Trust makes one canvass the possibility of making the Bachelor's degree more distinctive, selective, and meaningful. It is easy for the writer, who has spent about twenty-five years on this campus and has seen the philosophy at the foundations of the Selective Process for Admission gradually dominate the entire country literally over the prostrate bodies of innumerable cynical and often violently critical representatives of sister institutions, to think of one way in which the Bachelor's degree might be given- vitality and universal respect.

When the Selective Process was inaugurated in 1921 everyone had assumed almost for centuries that if the entrance units of a candidate added up to a certain total he was suitable material for admission, and was admitted. The Selective Process forced upon us by an excessive number of applicants proved with such impelling clearness that character, personality, school citizenship, taken in conjunction with accomplishment, had incomparably more prophetic value than entrance units that a year or two ago we abolished entrance units entirely, and now one hears everywhere throughout the country the commonplace remark, "Of course no one counts entrance units."

In order to make character and personality part and parcel of any selective scheme, whether it be for admission or something else, it is obviously necessary to devise procedures by which the character and personality of the individual can be estimated with some degree of accuracy and validity. During the last few years a great advance has been made in the solution of this problem by a committee of the so-called Eight-Year Experiment Plan of the Progressive Education Association, which has been attacking this important matter from an entirely new angle. This strong committee, representative of colleges and secondary schools, instead of trying to rate various traits of human behavior on some sort of a scale has successfully defined types of human behavior with such clarity and precision that any teacher who really knows a pupil can immediately classify him as of this or that type. This committee, after three years of continuous and arduous work and much empirical experimentation, has defined a half dozen types under each of some eight general behaviors, such as dependability, imagination, influence, inquiring mind, openmindedness, power and habit of analysis, social concern, and emotional responsiveness. For example, one type under dependability is, "Completes without external compulsion whatever is assigned bat is unlikely to enlarge the scope of the assignments." A type under influence is "His influence habituallyshapes the opinions, activities, or ideals of his associates." Under openmindedness one type is, "Wel-comes new ideas but habitually suspends judgmentuntil all the available evidence is obtained." And under emotional responsiveness two types are "Isemotionally stirred by becoming aware of challenging ideas" and "Those who respond emotionally toa situation or problem challenging to them becauseof the possibility of overcoming difficulties." It is certain that the studies of this committee are to have an important effect in any procedure which seeks to discover something about the character and personality of an individual. Their results, of course with modifications and improvements which experience can best furnish, can easily be adapted for use at the college level.

My prophecy, therefore, is that in the near future some brave college will attempt a scientific study of the characters and personalities of members of its graduating class—a study which probably can best be done about the middle of senior year when the men are well known personally to many of their teachers—and that from the results of this study the college will award several kinds of bachelor's degrees which will be selective and which will mean something. Such a series might include a degree

"With Distinction" for those men who, in addition to superior scholastic records, were rated highly in character and personality; a degree "With Promise' to include men of high, medium, and perhaps even low scholarship, who, because of the preponderant judgment of their teachers are believed to possess in strong measure all those elements of character and personality which mean eminent success after graduation; and finally, a "Pass" degree which would include not only students of low scholastic standing but also those of medium and even high scholarship who were judged to be possessed of none of those elements of character and personality that promise anything but mediocrity after graduation.

Dean of the Faculty

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

March 1936 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1936 By Harold P. Hinman -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

March 1936 By Warde Wilkins '13 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1928

March 1936 By LeRoy C. Milliken -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

March 1936 By Edward Leech

E. Gordon Bill

-

Article

ArticleWHY DARTMOUTH?

February, 1923 By E. GORDON BILL -

Article

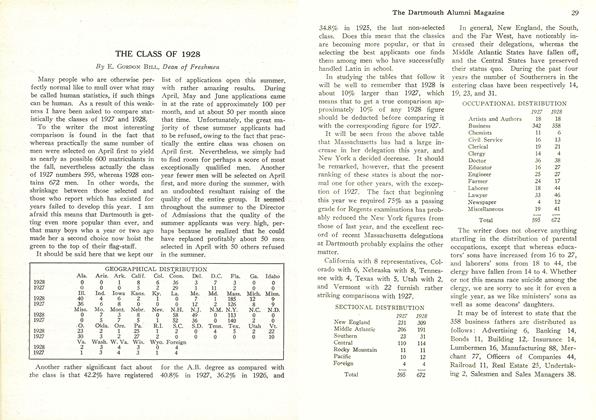

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1928

November, 1924 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

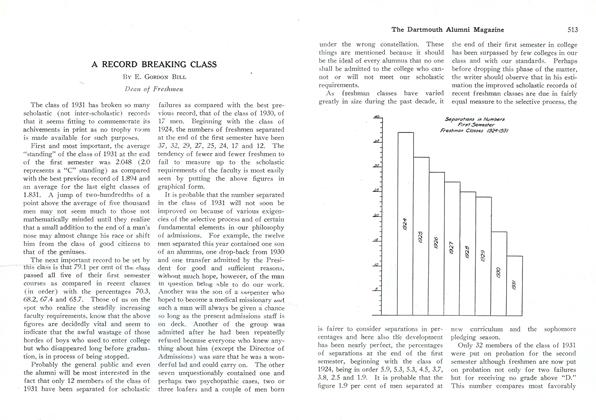

ArticleA RECORD BREAKING CLASS

APRIL 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

ArticleThe Class of 1932

November 1928 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

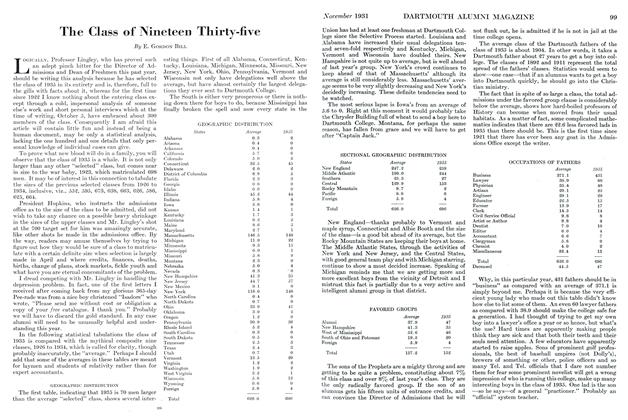

ArticleThe Class of Nineteen Thirty-five

NOVEMBER 1931 By E. Gordon Bill -

Article

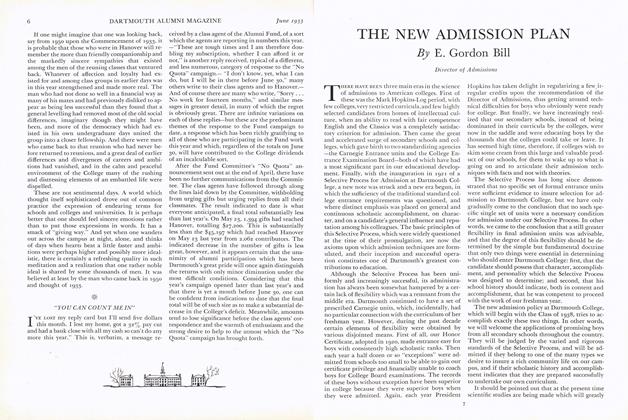

ArticleTHE NEW ADMISSION PLAN

June 1933 By E. Gordon Bill