IT is A pleasure to pass on to the readers of this column the excellent recommendations of Dean E. Gordon Bill. I give them with his own comments:

1. Chasing the Bowhead, by Captain Bodfish.

This autobiography of an old West Tisbury, Vineyard Haven whaler is bound to become a classic.

2. The Lore of the Lyrebird, by Pratt.

This book would be worth reading just to note two amazingly beautiful and rare pictures of the Lyrebird singing. Much of this very small book is uninteresting but the description of Mrs. Wilkinson's acquaintance and friendship with a male Lyrebird on Mount Dandenong, Australia, is an amazing tale.

3. Seeds, Their Place in Life andLegend, by Queen.

This little book will at least teach you not to make a practice of eating the seeds off your flower beds. It has one great fault—each sentence contains a new fact.

4.. Cosmic Rays, by Lemon.

It is seldom that an American scientist can write sufficiently simply about an abstruse subject to hold my interest. Professor Lemon has done just that in this little book, which certainly was written for the lay public.

5. The Anniversary Murder, by Eden Philpotts.

You will find this a top-notcher. It is not only good literature but a very unusual story in which the reader is fully as much interested in the development of a character as he is in the two murders which are spaced over a twenty-year period.

The best book of criticism I have read in a long time, with the exception of Logan P. Smith's magnificent Reperusals and Recollections (Harcourt), which I reviewed here some time back, is F. L. Lucas's TheDecline and Fall of the Romantic Ideal, published by Macmillan.

The first three chapters deal with the nature, past and future of Romanticism. Mr. Lucas, a Cambridge don, has an interesting definition of Romanticism along psychological lines. He calls it "a liberation of the less conscious levels of themind," whereas literature in the classical tradition is highly self-conscious, which is to say highly rational. Health, born in life and literature, he suggests, lies between excess of self-consciousness and excess of impulsiveness, between too much self-control and too little. This, it seems to me, is a more balanced statement than Goethe's remark that "Classicism is healthy, Romanticism is morbid."

Romanticism tends to be irrational, and in much of our contemporary literature Mr. Lucas finds, as any one of discernment must, a "mad world of irrationality" with the quality of nobility, common to all great literature of the past, almost wholly lacking. So, too, in much modern art. The fact is, that since the war especially we have been undergoing a deluge of irrationality not only in literature, but in politics and economics as well. This book gives a shrewd analysis of Romanticism, not only of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but of our own time. I must give one quotation, which I hope, will lead you to read this penetrating book. He writes: "And so, the Romantic, I suggest, wandering in the Woods of Dream, has often wandered too far; and got lost like the neuroticwho takes refuge from reality among thephantoms that haunt the moulderedlodges of his childish years. Those symptoms in individuals have become familiar;they are strangely like those of Romanticdecadence." His chapter on Coleridge as a Romantic critic is, so far as I'm concerned, the last word on that enigmatic figure.

While on the subject of criticism I wish also to call your attention to a new study of a great novelist entitled Joseph Conrad, by Edward Crankshaw, and published by The Bodley Head in 1936. The author owes most in his study to Percy Lubbock's superlative book The Craft of Fiction, and incidentally to Mr. Ford Madox Ford's and Mr. Richard Curie's studies of Conrad. Mr. Crankshaw attempts to show the way in which Conrad's genius worked as a novelist; the manner in which his spirit was made manifest. It is a fine book, and is sure to interest anybody who still reads and loves the work of that master of English fiction, Josef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski.

A FINE PROSE WRITER

For readers of travel books: Richard Curie's new volume, published by Stokes, Caravansary and Conversation. I have long argued that Mr. Curie is a fine writer of English prose, and this book, in my opinion still justifies my belief. He writes here of "Unchanging Fez," Caracas, Cornwall, Yorkshire, Kentucky, Buenos Aires, and of such men he has known as Cunninghame Graham, Amundsen, Gomez, Meredith, Watts-Dunton, Rossetti, Conrad, Galsworthy, Hudson, and so on. It is a book for the literary epicure, and will be enjoyed, also, by those who are unacquainted with caviar to the general.

I have recently heard that some distinguished members of certain Boston clubs are refusing to speak to those directors of Little, Brown & Company who were responsible for the publication of John P. Marquand's novel The Late George Apley. This story is probably apocryphal, but after reading the novel I could well believe it. Mr. Marquand, best known up to this time for his Mr. Moto stories, has written a superb book, better as a novel than Santayana's The Last Puritan. The dry bones of Boston society rattle, shake loose a little dust, and return to their antimacassars. Supposedly written by an old friend of the family's with the aid of family papers and letters, the resulting style is perfect Athenaeuma .... and should have caused gentle laughter among those endowed with what Meredith called the comic spirit. This is a civilized book and should be read by all. Boston may still be the hub of the universe but it evidently badly needs a little oil and grease.

A book which may become a little classic among nature books is October Farm, from the Concord journals and diaries of William Brewster, with an introduction by Daniel Chester French. The period covered is from 1851-1919. The publisher is the Harvard University Press.

R. G. Goodyear's second novel TheMyrtle Tree (the symbol of love), published by William Morrow & Co., 1937, is an extremely well written book, with undrtones both of comedy and tragedy. Love in all its guises, of man for wife and mistress, of man for man, of mother for child, of mother for daughter, is depicted in a series of episodes not closely interconnected, but nevertheless, having a unity of theme. It is a moving book and distinctly worth reading.

Reggie Fortune is back again in a full length novel White Land, Black Land. The story creaks a bit in parts, but Reggie's cryptic remarks are as pleasing as ever. Police Constable Bubb's brains would rattle in a mustard seed, but as this is a time worn device one doesn't mind . . . . much.

Scottish Journey, by Edwin Muir. Heinemann and Gollancz, 1935.

This book follows the plan, of Priestley's English Journey, and of Philip Gibbs' European Journey, and it is like them in its honesty of approach. Mr. Muir is a distinguished critic, a lover of Scotland, though an unsentimental one (Can this be possible?), and he here pictures Scotland in the slough of depression, and the picture cannot be a cheering one to Scotsmen, or to lovers of Scotland. The gloom that is Glasgow (Glesca as the old Scots call it) is painstakingly described, and in the author's comparison of this city with Edinburgh, he brings out facts which no one but a native would see. He analyses the aims of the National Party of Scotland, (which wants Home Rule) and arrives at the conclusion that in trying to please everybody they have lost ground, and Mr. Muir sees hope for Scotland only in some form of State Socialism. Scotland is apparently dying on its feet, and what will revive it, is really not clear, but as this seems to be true of many parts of the world, Scotland cannot be considered an isolated phenomenon.

Sometime after this issue will appear, Kenneth Robert's new novel NorthwestPassage will be out. This is a story of Roger's Rangers, their epic (and cruel) attack on St. Francis, and their magnificent march back to Maine, via Lake Meniphremagog, and the Connecticut Valley. Dartmouth men should be especially interested as part of the terrain of the novel is close to the College. If this book isn't a great success Mr. Roberts will probably insist that I refrain from further prophecy. I shall review it later.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsDeaths

April 1937 -

Article

ArticleFootball From the Inside Out

April 1937 By DAVID M. CAMERER '37 -

Sports

SportsFollowing the Big Green Teams

April 1937 By ROBERT P. FULLER '37 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

April 1937 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

April 1937 By Doane Arnold -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

April 1937

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1944 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE EDUCATION OF YOUTH AS CITIZENS

July 1947 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksFRATERNITY VILLAGE,

October 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleRESIGNATION OF PROFESSOR LYMAN

January 1915 -

Article

ArticleEngineering Design Workshop

OCTOBER 1965 -

Article

Article2008

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Jon Hopper -

Article

ArticleNuts and Sluts

MARCH 1978 By ANNE BAGAMERY '78 -

Article

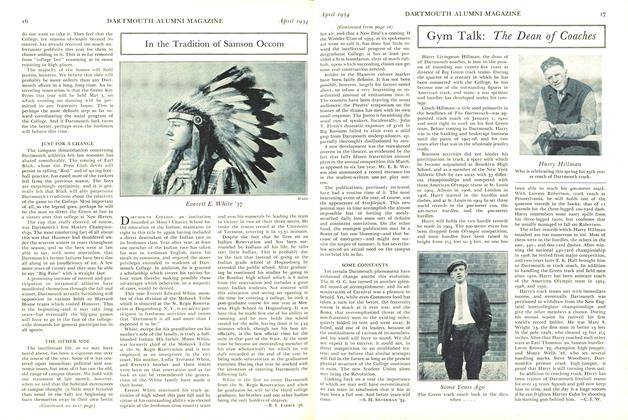

ArticleJUST FOR A CHANGE

April 1934 By S. H. Silverman '34 -

Article

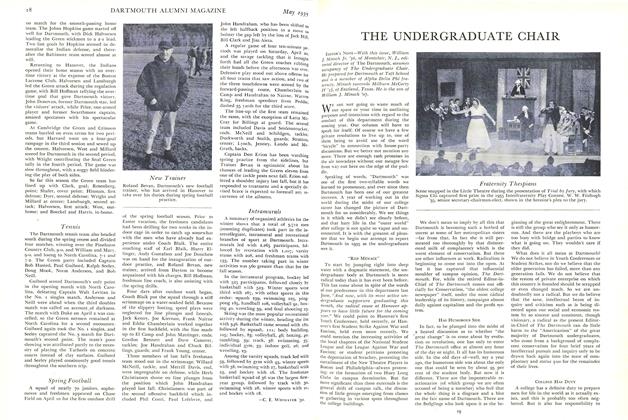

ArticleHAS HUMOROUS SIDE

May 1935 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36