In C. WILLARD HECKEL '35, moderator of the 184 th General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church, Professor of Constitutional Law, former and about-to-be Dean of the Rutgers University Law School, Diogenes might find the object of his quest—if he hasn't given up looking.

The outspoken Heckel actually does "make everything perfectly clear." He attributes his position as one of the first lay heads of the more than three-million-member denomination to his forthright stand on controversial issues. With this disarming honesty goes a joyful faith in the infinite power of the gospel of love, which he applies indiscriminately to those who agree with him and those who don't.

It was at Dartmouth that Heckel, a homesick undergraduate, first discovered "the closeness to God, the inner peace, that is the most cherished thing in my life." Other gifts of the College—fine teaching, stimulating courses, concern for the student as individual-he has retained throughout his distinguished career as an educator.

His first stated objective as moderator was to bring more young people and minority group members into the church. "The young are attracted to the gospel of Jesus Christ. They are searching for something to believe in that fits their aspirations for a world of love and justice. But many of them look at the institutional church with horror; they don't find the gospel of love there."

"If the church is to survive," Heckel warns, "it must become the prophetic voice of the Old Testament and it must speak to the corruption of the world—war, hate, racism, poverty. The most critical issue is the lack of commitment to the full gospel of Christ by church members, the lack of relevance of their faith to their lives."

Heckel is undismayed by controversy, which he considers one of the consequences of relevance. "Religion is not a soporific. If the church is to be the church, there will be tension. We must disagree, but we don't have to hate."Deliberately seeking out con- servative congregations, he tells them, "You don't have to like my ideas, but you must love me. As Christians, you can do no less."

The explosive issue at May's meeting of the General Assembly was a $10,000 grant to Angela Davis's defense, which he supported unequivocally as both a Christian and a lawyer. He credits his election on a rare first ballot to his straightforward stand. "The church honored me for my honesty."

He endorses a current fund-raising effort to send medical supplies to North Vietnam—beyond the general missions budget, which has long provided similar aid to South Vietnam. Asked by a TV interviewer if this not be treason, Heckel replied serenely, "In the words of Jesus Christ, there is no such concept as 'enemy.' Human suffering respects no demarcation lines."

As moderator, Heckel has traveled uncounted miles. He has preached in a South Dakota tent to a Sioux congregation; at New York's posh 5th Avenue Presbyterian Church; in a rural Appalachian strip-mining community—"a demonstration of the utter depravity of human greed"; in a Mississippi Delta town where he found two former law students working in legal assistance. He has been to Belfast—"more horrible than Newark during the race riots; there is nothing more obscene than killing in the name of Christianity." Post-Inaugural Sunday he preached at Washington's National Presbyterian Church on "Man: God's Trustee." Applying the legal concept of a trust, he evaluated man's performance as trustee of the planet, answerable in ultimate court, citing as breaches of trust destruction of the environment, despoilment by war and hate, economic priorities in- sensitive to human need, callousness toward human suffering.

Heckel attributes the recent upsurge of interest in law schools—Rutgers this year has 3600 completed applications for 180 openings, with 40 reserved for minority groups—to the fact that "young people now see in law an instrument for social change and social justice." Rutger's curriculum, expanded under Heckel's deanship, lays heavy stress on urban problems, strongly appealing to students bent on pro bono law.

Rutgers, his law alma mater, awarded Heckel his secondary honorary LL.D. when he resigned as dean in 1970, to return to full-time teaching, a pursuit he likens to "being paid to eat a steak dinner." His nine-year deanship covered the peak years of campus militancy, with, which he dealt with his usual compassionate concern—and "a word called trust, which we can't work without." He was deeply involved in Newark's racial turmoil, as president of the city's anti-poverty agency and as dean of the school which became a center for mediation.

With a rare gift for budgeting time, Heckel has managed a full course load this year along with his church duties, writing and reading papers on planes, between planes, or wherever he could find a free hour. Even his devotion to opera has not been entirely neglected: "Through the goodness of the Lord," he says with a grin, "my tickets at the Met were for Tuesdays, when I'm always in town for classes." Although he has agreed to. become acting dean in July, after his term as moderator is over, he plans to return to full-time teaching when a permanent successor is found.

His reason for resigning from administrative responsibilities at 57 was simple and direct, quite typical of Willard Heckel: "The most precious thing I have is the rest of my life, whether it be five minutes or five years. I invest time as some people invest money. I must spend it in the classroom."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

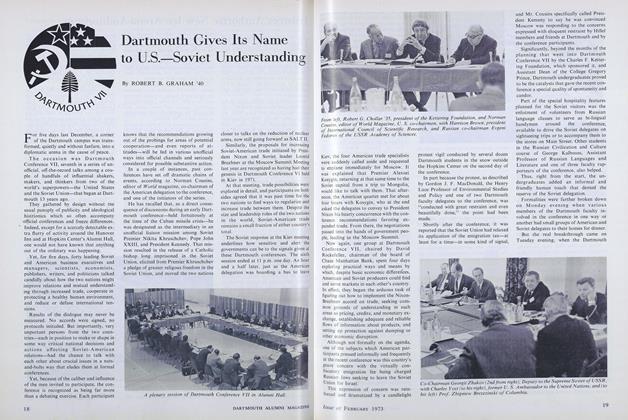

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1973 -

Feature

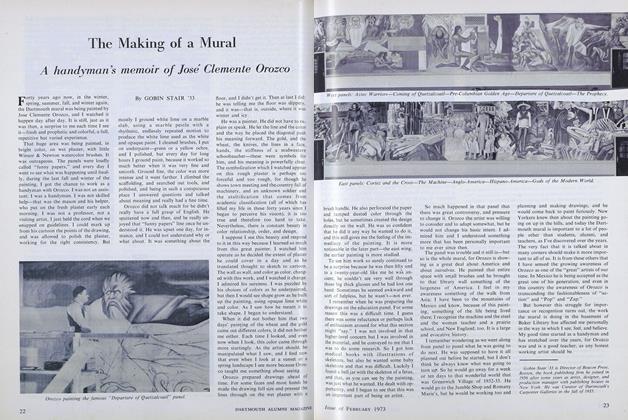

FeatureThe Making of a Mural

February 1973 By GOBIN STAIR '33 -

Feature

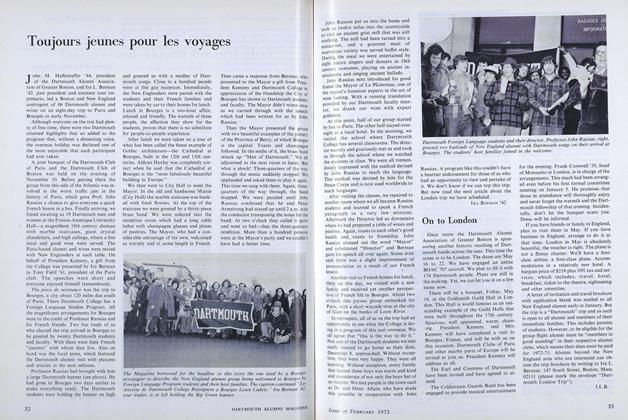

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

February 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

February 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

Article

-

Article

ArticleDRAMATIC ASSOCIATION

March, 1914 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA OPENS SEASON'S PROGRAM

APRIL, 1927 -

Article

ArticleClass Day Exercises on the Campus

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleAssociated Schools—Fund Contributors

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleMiscellany

November 1950 By C. E. W. -

Article

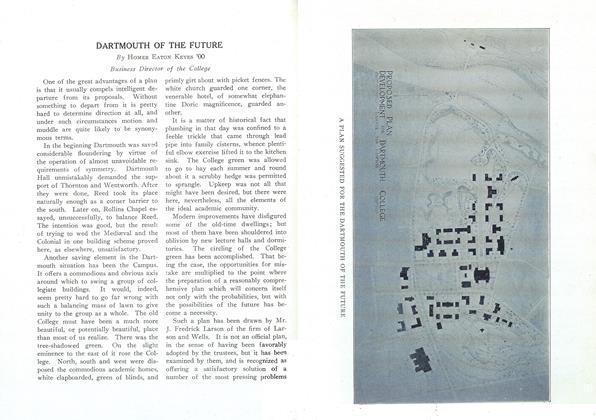

ArticleDARTMOUTH OF THE FUTURE

July 1920 By HOMER EATON KEYES '00