By Burton Bernstein '53.Cleveland: World Publishing Company,1963. 143 pp. $3.95.

It's not very generous to take someone's frank admission and turn it against him. Still, this is what priests do in the confessional, what teachers do in the classroom, and what I shall do with Burton Bernstein's lively book - or, rather, non-book.

The Lost Art is a collection of about twenty-five short conversations, plus a twenty-sixth which begins on the front of the dust jacket and extends to both flaps. There is no connection among them. Each is an independent dialogue between a couple of characters whom you identify only as you get into the conversation. There's a very good one between a little girl named Janie, who wants to play a game of her own invention called Peaceful Corner, and an even smaller boy named Alexander who would rather watch TV. There's a rather offensive one between two homosexuals waiting in line for what seems to be a night-club performance. There are a whole series which say something about human relations in the city (nearly all the conversations take place in New York, where Mr. Bernstein is a staff writer for The New Yorker). In each the primary emotion is a sense of horror at being forced into contact with a stranger. In one a man sitting in a small city park gets trapped into talking to a very dull sanitation worker. In another a woman having a cup of coffee gets trapped into a conversation with the rather pathetic woman on the next stool. In a third, a college girl named Luanda Meltzer is trapped on the telephone by a date-seeking lout whom she knows only in the sense that they are in the same economics class, probably at NYU. And so on.

To my taste, about five of the conversations come off, another five nearly do, and fifteen are more or less talented self-indulgence on the part of the author. The worst of it is that Mr. Bernstein seems to know this himself. That twenty-sixth conversation, the one that begins on the front of the dust jacket, is between a book salesman and a woman looking for something to give her sister in Brooklyn Heights. One part of it goes like this:

"Don't you think it's a little coy to put dialogue on the cover like that?"

"Frankly, yes, Madam. But it's supposed to be a very entertaining and revealing thing, for a non-book."

"What's that?"

"A non-book is a book that's not really a book in the conventional sense, but nevertheless is in book form. Do you see? It's a term that's generally used pejoratively."

"Oh."

Oh, indeed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

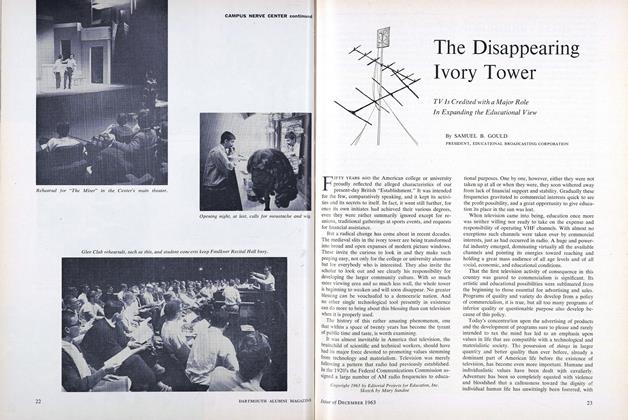

FeatureThe Disappearing Ivory Tower

December 1963 By SAMUEL B. GOULD -

Feature

FeatureHORNING: Invention of the Devil

December 1963 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

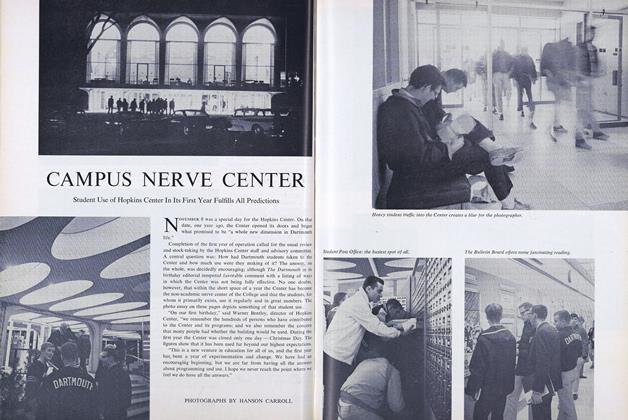

FeatureCAMPUS NERVE CENTER

December 1963 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

December 1963 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1963 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1963 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR

NOEL PERRIN

-

Books

BooksTHE DISPLACED PERSON'S ALMANAC.

March 1962 By NOEL PERRIN -

Books

BooksUrban Romantics

April 1976 By NOEL PERRIN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

MAY • 1988 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleO Wisest Vox, All-Knowing Vox, Silent Vox

DECEMBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleDo Good Computers Make Good Writers?

APRIL 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

MARCH 1999 By Noel Perrin

Books

-

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

JANUARY 1971 -

Books

BooksFIVE CUMMINGTON POEMS:

February 1940 By Edward Fritz '40 -

Books

BooksMANUAL ON RESEARCH AND REPORTS,

December 1937 By Harold J. Tobin 'l7 -

Books

BooksDOCTOR DESTINY

June 1947 By John F. Gile '16 -

Books

BooksPAYMENT FOR PAIN & SUFFERING: WHO WANTS WHAT, WHEN & WHY?

MAY 1973 By MICHAEL L. SLIVE '62 -

Books

BooksAN OUTLINE OF ECONOMIC PRINCIPLES AND PROBLEMS

February 1940 By Richard L. Funkhouser '30