SOUTHERN JOURNEY AND ADVENTURES OF DARTMOUTH SKIERSDESCRIBED BY CAPTAIN OF THE VARSITY TEAM

LATE SPRING is a dreary time to ski. Everywhere are signs which toll the death of grand old Winter: the whisper of the inevitable buds on trees, and the plaintive notes of the cattle early turned into the muddy fields to search for ambitious blades of grass; the boisterous baritone of the coffee-colored brooks, o'er charged with cakes of ice, pieces of wood, rusty beer cans, and other treasures of which they have despoiled old Winter; and the "slock, slock, slock" of the few final ski boots that toil doggedly up the cataract of mud and stumps, which was once the Sherburne Trail, for a last schuss in the palm of Tuckerman's Ravine all these things may stir others into lyric frenzies, but to the skier Spring is drear.

This is the time of year when plans to foil the dictates of the coming summer weather crystallize into definite shape. And so with us. During the early spring many things happened suddenly. First, the Australian and New Zealand Ski Year Book considerably upset the equilibrium of many of us who were looking apprehensively at the wane of the Winter Season. Then, Jim Laughlin, the Brobdingnagian bullet of the boards from Harvard, and Lilliputian Dick Durrance decided to trade a summer here for a winter below the equator. The next thing I knew, my own ordinarily reasonable brother Steve was babbling like a man insane about skiing in the Antipodes, and had arranged with Dick and Jim that we make it a team of four.

From here on until we were aboard the Mariposa on June 22d, my brain records only chaos. Somewhere in the maelstrom of that last month we managed to get our team sanctioned as an official U. S. ski team, to get tickets, birth certificates, passports, pictures, and samples of typhoid fever, a million square yards of film for our boots and new laces for our cameras, wax, tools, steel wool, books, winter and summer clothing, white suede shoes to develop films in, and gallons of chemicals to make a hit with the girls on the boat, fillings put on our skis, and steel edges on our teeth. In addition to all this, we were still engrossed in profound intellectual activities at College, with final exams coming early in June to be given some slight consideration.

And so I say, it was chaos .... then quite suddenly we found ourselves on the unsteady decks of the Mariposa following down the Pacific swells into the sunset. Dick and Jim seemed to notice nothing unusual about boat travel; they slept, they pursued the inclinations of their hearts, they bounded about the tennis court and scraped the deck with shuffle board rakes, they consumed prodigious quantities of food. But as for Steve and me well . ... ; sometimes we had our little reservations about this trip.

Honolulu, Hawaii, the flower shop of the Pacific, was our first stop. A body of Dartmouth alumni and some members of the Ski Club of Hawaii (They ski in winter on the slopes of one of the big slumbering volcanoes.) met us at the dock and smothered us in garlands of blossoms. After we had seen the pineapples turned into juice and sampled the result approvingly, and after we had seen the Pali a cliff where good old King Kamayamaya (or some such mayonnaise receipt) had enjoyed himself of dull afternoons by pushing his captives into the void we turned our attention toward Waikiki Beach.

We banqueted in royal style with the Dartmouth alumni and then went surfing in an enormous war-whoop canoe. None other than Duke Kahanomoku, a grand fellow and marvellous specimen of physical perfection, was at the steering paddle. With the bow of the boat a fountain of spray and the stern riding high in the forming crest, we roared into the beach, surrounded on both sides by bronzed madmen who skimmed down the impetuous incline of the waves, shouting, reeling, leaping, cursing, falling off, vanishing behind in the foam.

The verdant isle of Samoa was the next to rise out of the flat horizon. Here, we had heard, one could secure almost anything from a half a dozen wives up in trade for an old shirt, and while we were not specifically looking for wives, still it seemed like a bargain. Accordingly, we went ashore with several shirts and waited until a half hour before the boat was to leave in order that they would have a maximum value.

From Samoa on the weather became unbearably hot. An oily sea smoldered under the blase of the equatorial sun, and nights were scarcely any cooler. Moonlight itself seemed hot and very unromantic. We essayed several times to sleep on deck, for it was impossible to sleep in the humidor which was allotted to us as a cabin. But this was not successful either, for the funnels covered us with a couple of inches of grit, and at four in the morning the crew blasted us off the decks with fire hoses. At this point the others decided to go below while I, as a last recourse, tried sleeping on a sofa in the lounge where I was awakened at six o'clock by a Catholic Mass.

New Zealand was a welcome sight; eighteen days of fallowing in the slothful trop- ical atmosphere is not suited to the temperament of a skier, whose system is attuned to lower temperatures. In Auckland we received a cold greeting by the weather and a warm one by members of New Zealand's largest ski organization, the Ruapehu Ski Club. With them we banqueted and the wreaths of flowers this time came in verbal form.

As to what we were eating and with whom we were eating, my mind is a complete blank the reason being that I had been elected by my generous companions to attempt what usually masquerades under the innocent phrase—"to say a few words." I have never known a skier who was truly eloquent (except on the occasion of sweeping out a slalom flush or of getting hung up in some trees in a langlauf race); perhaps they, knowing and loving their subject so well, can sense the impotence of words. However, on this occasion I was in rare form—or rather, what I said had rarely any form—and I managed to "say a few words" in the sense that of all the curious sounds I was able to specially create for the occasion, only a few were recognizable as words.

ARRIVING WITH BAGGAGE

After having stored our trunks of summer clothes, we boarded the Wellington sleeper (a misnomer in second class) and at midnight the station of National Park welcomed us with a chill embrace. The train was held up a half hour disgorging our equipment: five suitcases, a sixth full of wax and tools, a seventh full of assorted camera attachments, four packs, twenty pairs of skis and countless poles. To keep a caravan of this size together is, I think, a triumph—let alone doing a little skiing on the side.

That same night we arrived at the Chateau Tongariro on the lower slopes of Mt. Ruapehu and were greeted by its genial host and hostess, the Bayfields. After exchanging notes with them and meeting some of the local skiers, we retired to bed and new surprises. Heavy-eyed and in blissful ignorance of custom, I fell into the soft blankets only to be startled out of my pajamas by some frightful squashy object which gurgled amicably at me from the recesses of my bed. I thought some card was keeping his aquarium in my bed—certainly it was a turtle or a whacking big jelly fish. After I had ricochetted from the ceiling I cautiously uncovered the marine life, and there was the innocent face of a steaming hot water bottle smiling up at me. Custom No. 1.

Custom No. 2 caught us at the susceptible hour of six A.M.; a dainty maid tripped in, violently rattling an armful of dishes it was early morning tea, which is all right at a reasonable hour, but no substitute for those last delicious moments of insensibility. All New Zealanders start with a bracer of tea at this time, and from then on throughout the day they rebrace themselves at half-hour intervals.

But we had come to ski and there before us, gilded with the early light, great white Ruapehu stood—austere in the wild jumble of ragged, snow-dusted rock which characterize its barren foothills and flying buttresses—serene in the meticulous smoothness of its higher contours. However, the sullen sweep of clouds which menaced the plains below surged up and engulfed the mountain just as we were preparing to set out. Nevertheless, we drove up as far as the road led and then, with flagging steps, scrambled among rocks until we reached the Ruapehu Ski Club cabin. Here it was snowing and blowing viciously, and with little success, except in engraving the bottoms of our skis, we practiced slalom running.

The following day was not so bad and we were able to ascend a high gully and covered glacier tongue on the northeast side of the mountain. The party was materially improved by the addition of Johnny Loveridge, guide and skier at the hotel, Ted Ferrier of the Ski Council, and jy[r. Bridgeman, photographer from the government Tourist Bureau.

In the gully, indeed everywhere above the foot of the glacier, the snow was disconcertingly hard packed and rippled by the wind. But the surroundings! sunshine, jagged cliffs flanked by sweeping snow fields; and out beyond and below, a sea of clouds like silver wool, slow-moving, through which protruded the symmetrical, glistening sides of the volcano Ngauruhoe.

It is better to admire clouds from afar where their superficial loveliness is most apparent while intimacy brings only disillusionment. As we skied down through the gray, damp mists everything had become armor-plated with ice; steel edges scraped and rattled, our ankles ached, fillings started from our teeth. Back at the Chateau we spent a hilarious evening with the guides, singing' war songs and sampling (in discrete quantities, of course) the excellence of New Zealand beer. There was dancing too, where we could leap and pirouette with abandon, for no matter how clumsily we trampled on the girls, they would say apologetically: "Please excuse me, but. I am not used to these American dance steps. Won't you please show me that one again?"

But as the essential thing, snow, was not yet good, it was decided that we should go on to the South Island and return to Ruapehu after a couple of weeks on the precipices of Mt. Cook.

THE ODYSSEY CONTINUES

Accordingly, we gathered up our toothbrushes and the rest of the outfit and continued south a journey notable for the fact we barely made connections with boats and trains in half a dozen places, arriving in Timoru decidedly the worse for wear.

At Timoru, Harry Wigley, the best of the South Island skiers, met us to drive us to Mt. Cook. My recollections of the space which separates Timoru from The Hermitage are indecipherable; there is a kind of hissing sound filled with flashes of steep tan hillsides, tufted yellow grass, flying gravel, apprehension, sheep, lakes, a cold wind then at last stability, association with the earth once more, and The Hermitage almost in the shadow of the pyramid of Cook.

The snow was still farther up in the mountains, and on the morning of the following day we found ourselves in a bus creeping along the edge of a precipice above the Tasman Glacier. Here and there sections of what once was a road could be recognized; in other places only the power of mind over matter sustained the bus. By noon four very pale and very shaky Americans were filling up the Ball Hut with their travelling effects.

Here was snow! powder snow—deep, heavy, a cold shower to fall into. And here was country! rugged, wild, awful country designed to inspire admiration and respect in the hearts of the ordinarily rash. The long, scarred arm of the Tasman Glacier reached up between the massive peaks and had its white fingertips on the tops of many mountains. Above us everywhere were these lofty, silent walls whose stillness was broken only by the muffled booming of invisible avalanches.

Mt. Cook itself, the crisis of the southern Alps, seemed to hang almost overhead. An eight thousand foot vertical cataract of ice and rock separated the Ball Glacier from the southern point of the final ridge. Here all day long prodigious avalanches were crumbling down, smashing and smoking through the chutes and pouring out upon the valley of ice below.

Nor were avalanches our only concern. Since skiing on the side of the mountains is impossible, one is limited to the gentler glaciers. Rather large and ominous cracks in the ice are not uncommonly associated with glaciers; and even when the snow has safely bridged most of them over, skiing among the snow waves in whose trough you can feel unseen crevasses lurking and seeing now and again these great open wells which drop into the ultramarine gloom of the glacier bottom—well, things like this unsettle the equilibrium of skiers brought up on the delightful rocks, stumps and trees of our New England trails.

Almost every night Dick had a nightmare about falling into crevasses, and he would pull his bunk and half of the Ball Hut in with him while we stood helpless on the brink, bathed in sweat and losing headfulls of hair at the clamor.

We could never quite understand why the New Zealanders paid so little concern to the trifling crevasses and avalanches. They blithely skied all over the glaciers and thought it was a great joke when Harry Wigley tried to slalom between two poles which were used to mark a hole. To them it was unbearably funny when some novice fell on the very edge of one and with his paling face shoved snow into the fathomless pit. However, no one has actually been hurt and so we learned eventually to ski with some semblance of abandon.

For a week we enjoyed alternate rain and snow and while the weather never cleared long enough to allow a long tour from the Malte Brun Hut, over the saddle by Elie de Beaumont, to the other side of the range and the Franz Joseph Glacier, yet we had good skiing almost every day. Evenings were spent in writing, reading, reminiscing and developing pictures and, I must not forget, in augmenting the cache of empty beer bottles under Harry Wigley's bed. For those who liked their beer mixed with marine life, Harry also had a keg in which, by some strange mutation, several species of algae and, we suspect, fish were to be found.

Twice we ascended die long Ball Glacier to the top of the downhill course and the Ball Pass. Here was a grandstand view of the Southern Alps which was of ineffable force. My discriminating pen dries up at the thought of attempting a description; I leave it to the photographs to give some faint suggestion of reality.

The snow, however, on these two occasions was scarcely to be eulogized. Once it was powder so deep that we had the impression of wading down hill barely able to keep the chin above the surface. The next time, a frightful breakable crust terrorized our confidence.

My own impression of my hectic downward progress was that most of the time, through prodigious exertion, I was able to keep one ski ahead of me; the other meanwhile was windmilling around in a detached way somewhere in the vacuum just astern of my neck. As the speed increased things would become more and more unrectifiable struggling, leaping, agony of confusion, bang! and chill stillness. In this dramatic fashion I punctuated the entire downhill course the usual symbols being a long visible exclamation mark followed by several short audible ones.

THE FRIENDLY COMPETITION

When Brian McMillan and Brian Murphy arrived from the North Island, the teams were complete and informal competition was arranged. I use the word "informal" with reluctance and only because I know of no other word which approximates the spirit of our races. It was a spirit rarely to be found in races of any sort—particularly in races where, presumably, the reputations of two countries are involved. "Informal" must not be considered synonymous with "haphazard," "careless," or "negligent" a thing which many formal races easily achieve. Far from it. Our races were run over jumps and slalom courses set by ourselves with very little waste of patience and without a single mistake being made.

The race spirit I allude to was the high sportsmanship of the New Zealand boys. Sunshine and the inspiration of such magnificent surroundings may have had something to do with it, but I hesitate to put too much stress here. Rather, I think, it was the wholehearted geniality and friendliness which we found so evident in New Zealand being more eloquently expressed through the medium of sport. Never at any time were we made conscious that this was a New Zealander or an American about to jump. Never did the idea that this was merely United States vs. New Zealand, or Mars vs. Jupiter, insinuate its serpentine influence into our easy comradeship and gay collaborations. This was racing which we had scarcely dared to hope for.

ALL IN FINE SPIRIT

The New Zealanders seemed more eager about the jumping and slalom competitions, where they knew we had superiority, than about the downhill where we were on a par. And I know that in the few practice slalom runs which we had together during the days before the actual competition, the other team benefitted materially from the example and voluntary instruction of the ever-helpful Dick.

For the jumping we built a snow take off above a little pot hole in the lateral moraine of the Ball Glacier. It was quick on the take-off and quicker at the bottom, with knoll and landing hill about equal in length. On a bright day, with the big guns booming across the valley on the Caroline icefall, the competition was held. Harry Wigley and Brian McMillan were the only members of the other team who had ever jumped, and had done very little at that.

"Oh, well," said Harry, smiling and removing the pipe whose absence, from its long association with his face, gave Harry an air of incompleteness, "We'll have a go at it but I hope I last long enough for another go at that beer." Brian McMillan only grinned in general accord.

Harry's "go at it" was at least spectacular. In the out-run he did a handspring into the deep snow and ended up at the far end of a furrow large enough to bury a dinosaur with his skis lazily swinging overhead in the eddying breezes.

The Little Man won the competition easily with the longest jump of 95 feet; I was second, Steve third, and Brian McMillan, Jim Laughlin and Harry Wigley finished next in that order.

The following day was another one just as the doctor ordered. With the exception of the crust on the first schuss and flat below, the entire two miles were velvet with fresh powder snow. At the start of such a race one is always full of resolutions; one grits the teeth in commendable determination. But once the race has started everything thoughtful seems to vanish, and one becomes the only stationary thing in a world of motion, a receiver to sensations but very little an effecter of compensations

Aggravated and amused by a barrel-roll at the very top, but soothed by the even hiss of the urgent skis, I followed their spray over the exhilarating swoops and suddenly found the race over as far as I was concerned. Almost immediately Harry came over the brow of the last half mile schuss. Erect and sure as a moral condemnation, he rushed down upon the fin. ish. Jim, Brian, Mac and Steve finished almost simultaneously, with the Little Madman turning the snow into steam just behind.

These were the results:

DOWNHILL (Previous record 3:25)

1. R. Durrance 2 :36 2. H. Wig-ley 2:55 3. J. Laughlin 3:17 4. B. McMillan 3:19 5. D. Bradley 3:22 6. S. Bradley 7. B. Murphy 8. A. Wigley

That same afternoon we ran the second of two slaloms in a steep gully behind the Ball Hut. Dick was elected course-setter and with a clear eye for a smooth, fast, liquid course, he created an excellent sequence of exacting situations which included a series of sweet "S" corners at the top, an unavoidable icy descent, more fast turns and a six-gated flush just before the finish. Before the two runs were completed dusk was beginning to dissolve the details of the course. I shall never forget the lonely figure of the last runner, Steve, silhouetted on the ridge-top against the fading splendor of a marble sky, calling plaintively into the blue void before him to as,k if anyone could lend him a candle.

This is how we finished in the two days of slalom racing, with two runs being totaled for each course:

SLALOM

Ist Course R. Durranee 1:49 D. Bradley 2:12 A. Wigley 2:36 3/5 S. Bradley 2:42 B. McMillan 2:42 1/5 J. Laughlin 2:58 2/5 B. Murphv 3:5 4/5 H. Wigley 3 :17 3/5 2nd Course R. Durrance 2 :13 D. Bradley 2:31 3/5 S. Bradley 2 :41 J. Laughlin 3:24 B. Murphy 3:34 1/5 B. McMillan 3:46 H. Wigley 4:21 A. Wigley Disabled

A REAL BUZZARD

The weather had been perfect for our three races; only the langlauf remained. That very night a blizzard rocked our Ball Hut cradle; we slept marvellously, and next morning the rain and sleet were roaring by the windows so fast that it looked as if nature had taken up hydraulic mining. Therefore, the langlauf had to be cancelled, and in the opinion of almost everyone the weather was still perfect.

That afternoon we had to say farewell to austere Mt. Cook and its warm-hearted citizens which may have to last forever. We were happy that the two Brians were returning with us to the Chateau Tongariro. They spent most of their time acquiring a feeling for American expressions.

jylt. Ruapehu was now well coveredboth with snow and ice. It is a cool volcano, and quite isolated from other ranges, as are all the mountains in the North Island. Consequently the moist winds from the nearby Tasman Sea are continually bathing its sides with freezing mists. This is really a tragedy, for never have I skied on more gloriously varied terrain. A downhill course of several thousand feet descent over rolling steppes and basins, through picturesque gulleys and beside shaggy bluffs is the finest in all New Zealand and Australia. It should be wonderful in Spring with corn snow!

To THE SUMMIT

It was too icy for a downhill race, and so we ran several slalom races in an open gully where the brilliant sun and our steel edges could penetrate the sheen. The day afterward we had the opportunity to tour upon the top of the mountain a thing we had been longing to do. Above the rambling clouds, we found the snow was dry and hard. A day here was scarcely enough to establish an acquaintance with the vast character of this mountain.

But our leave in New Zealand was expiring. In Auckland the night before we set sail for Australia in the Monterey, the Ruapehu Ski Club graciously made us Honorary Members a thing which unfortunately entailed "a few words" from us. I copy the following from my diary: "We were greatly touched by such a gesture. The little badge is one of those things which are precious, not in itself, but for recollections inseparably associated with it. The rugged snow country, hot water bottles, coinage, speeches, people ; we won't soon forget our many hosts and hostesses, nor Brian Murphy trying to get the hang of American slang and Brian McMillan reverting to his native expressions on getting tangled in a flush; nor Sandy Wigley's laugh and reluctance to allow a race to interfere with sleeping, and finally Harry Wigley, straining the seaweed and minnows from the beer while trying to sing selections from Show Boat in a key two octaves below the piano."

[ED. NOTE: Readers are referred to the American Ski Annual for 1937-38 for the further account of the trip, as told by Mr. Bradley, including the visit to Australia and the races there. It is possible only to publish the New Zealand section of the whole story in these pages this month. The editors are indebted to Nathaniel L. Goodrich, librarian of the College and editor-in-chief of the Annual, and to the Stephen Daye Press, holder of copyright (195)7) on the book, for permission to reprint the article and also for the kind loan of illustrations.]

DAVID J. BRADLEY '3B Senior fellow and captain of the ski team,whose description of the skiers' trip toNew Zealand last summer appears in thesepages. His home is in Madison, Wis.

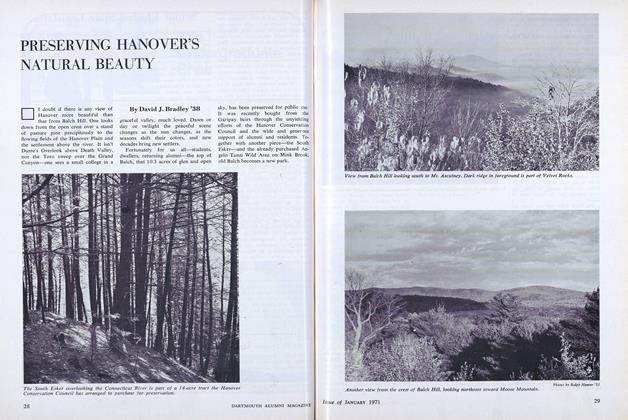

MT. COOK, NEW ZEALAND

ON MT. RUAPEHU

RICHARD DURRANCE '39, SPEED "DOWN UNDER"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Potentialities of Education

April 1938 By FREDERICK E. WAGNER '38 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1938 By BEN AMES WILLIAMS JR. '38 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1937

April 1938 By Donald C. McKinlay -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1938 By Hap Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

April 1938 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1926

April 1938 By Charles S. Bishop

DAVID J. BRADLEY '38

Article

-

Article

ArticleJANSSEN EX-'21, COMPOSER, RECEIVES HONORARY DEGREE

December, 1923 -

Article

ArticleExpand Group Security

July 1949 -

Article

ArticleSummers in Africa

NOVEMBER 1988 -

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1952 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

June 1947 By G. W. Woodworth, H. L. Duncombe Jr. -

Article

ArticleGood Will Ambassador

By TED BREMBLE '56